Advertisement

For Scientists, HIV Vaccine Is Proof That Infection Rate Can Be Reduced

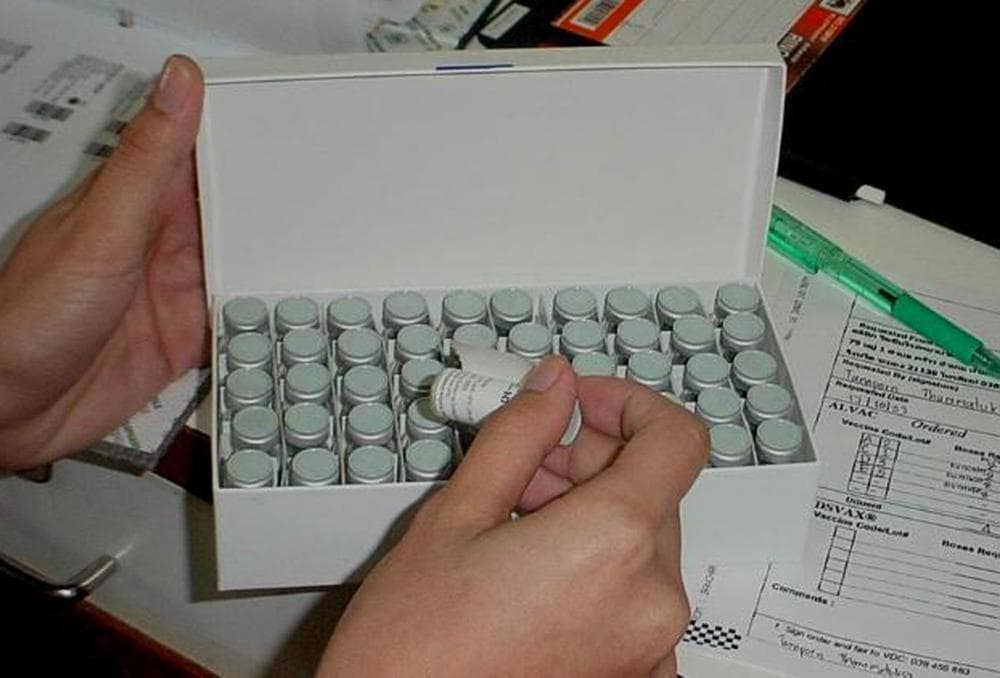

For the first time ever, a vaccine has prevented infection from the HIV virus that causes AIDS. The vaccine cut infection rates by only 31 percent, but years of failed attempts had convinced many researchers that a vaccine would never be successful.

For the first time ever, a vaccine has prevented infection from the HIV virus that causes AIDS. The vaccine cut infection rates by only 31 percent, but years of failed attempts had convinced many researchers that a vaccine would never be successful.Dr. Tim Johnson is medical editor for ABC News and a frequent contributor to WBUR's Here & Now. He spoke with host Robin Young on Thursday. (Listen to their conversation on hereandnow.org.)

Robin Young: Dr. Tim, in your view, how big is this news?

Tim Johnson: Well, it's big news, but it's not a breakthrough in the sense that this is now ready for treatment. The ordinary vaccine success rate that is targeted before commercial use is somewhere between 70 and 80 percent. In this particular trial the researchers had even said that before they would even consider licensing it or producing it for the Thai people where it was tested, it would have to be above 50 percent.

So 31 percent doesn't meet either of those goals, but it does show for the first time that we can do something about reducing the infection rate. That excites researchers that are obviously going to go over this data and this trial to find out why it worked when it worked and see if they can do a better job.

You mentioned that the study took place in Thailand with 16,000 volunteers there. It was research backed by Dr. Anthony Fauci, from the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, and the U.S. Army. How did they conduct this, what did they do with those 16,000 volunteers?

Well, that's another part of this complicated story. They divided them in two groups. One group got six shots over a six-month period with two different vaccines. They got a shot with one of the vaccines from the first four months, and one with the other vaccine for the last two months.

And they used two different vaccines because they act differently. One boosts the immune system, the other sort of boosts white blood cells. And so they figured that even though these vaccines had failed when tried individually, maybe in combination they would work.

Well, they sort of worked in combination. Now, remember, you're talking about giving six shots over six months. That's not easy to do anywhere, particularly in a third-world country. But they did find that the ones who got the six shots of the real stuff had a 31 percent reduction in infection rate versus the ones who got six shots of placebo.

Are there any ethical questions raised here? Because that presumes that these people were allowed to go about what was probably risky sexual behavior, or even maybe got it through drug use or blood transfusion, but in any event, these were people who were not told not to do those things because they were part of this project.

Well, in fact, both groups were given counseling, were given condoms — so they were told to do the usual things. The point is that the ones who got the vaccine did even better than the ones who didn't.

Right, one of the worries with some vaccines is that a percentage of people who receive the shot might actually contract the illness. That happened with early polio vaccines. But we're hearing that's not an issue here.

That is not an issue because neither of these vaccines is made from polio virus, dead or alive, so it cannot actually cause HIV. They used genetically-altered material, not the HIV virus.

Well, we say these test trials took place in Thailand — they used particular strains of HIV found in Thailand — do we know that we can extrapolate that these shots might reduce infections elsewhere where there are other strains?

No. Simple answer. And that's one of the many problems the researchers will now wrestle with in going on with the research. We know that the AIDS virus mutates very easily and so one of the great issues with any vaccine, but particularly with an AIDS vaccine, is that you might develop it, and the virus mutates and will no longer be effective.

There are many huge issues before we can begin to think about this as a product that we will give worldwide, or in any big country. One of the big decisions now, Robin, is: Are they now going to go back to the people who got the placebo, at least, and give them the six real shots now?

They have said that they would do that if they got better than 50 percent results, they didn't, but I expect there will be some pressure for them to do at least that.

Well it sounds like the bottom line now is behavior-related.

Very much so, and as Tony Fauci himself said about this research: This is not a breakthrough, this is a beginning.

This conversation originally aired Thursday, Sept. 24, on Here & Now.

This program aired on September 24, 2009. The audio for this program is not available.