Advertisement

BU Researchers Connect Former NFL Player's Suicide To Brain Disease

Resume

Dave Duerson, the former safety for the Chicago Bears who killed himself in February, had been suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — and the degenerative brain disease likely contributed to his suicide.

"There's no question that because he had CTE, he had difficulties with depression, he had difficulties with cognitive function, he had difficulties with impulse control," said Dr. Robert Cantu, a lead researcher at the Boston University Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy, where Duerson's brain was examined. "That all puts one at higher risk for taking one's own life."

The news was announced Monday by the CSTE. Before his death, Duerson sent text messages to his family requesting that his brain be left to the center, which he called the "NFL's brain bank." He then shot himself in the chest, which many have speculated was to preserve his brain for the research.

Duerson's actions are a somber indication of how seriously the world of professional athletics is starting to think about the long-term risks of contact sports. Much of that is because of the CSTE. In the three years since its creation, the center has identified CTE in the brains of more than 40 athletes, leaving the NFL and other professional sports leagues with little choice but to pay attention.

Looking For Tell-Tale Signs

Dr. Ann McKee is a co-founder of the CSTE and runs its brain bank, which is housed at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Bedford. If an athlete agrees to have his or her brain donated to the center, the body comes here to the bank after death for analysis — starting at the morgue.

"It's actually a very nice little morgue," Dr. McKee said as she lead us around. "It's just for brain tissue, we don't do all the rest of the organs, so that's very nice for me because it's relatively blood free."

“I think the biggest problem for football is going to be: How do we deal with those sub-concussive hits, those thousands of hits that occur just in the course of a single year, just from the way the game is played?”

Dr. Ann McKee

She pointed out the six refrigerated vaults against one wall, where a body is kept before the autopsy is performed, and the stainless steel table in the middle of the room where the body will be placed for one of Dr. McKee's assistants to remove the brain from the skull. Around the room are several large freezers where the brains themselves are stored at very cold temperatures after removal.

At the moment, three of the brains are not in freezers, but sitting instead in little buckets in a sink near the autopsy table, awaiting basic examination. All that Dr. McKee knows about the athletes these brains belonged to is that one was a youth athlete, one was a professional hockey player and one was a professional football player. She has no idea if that football player was Dave Duerson.

The lack of information is intentional, to ensure that Dr. McKee's analysis is as unbiased as possible.

She takes the brains of the two professional athletes out of their buckets and sets them side by side on the table. Even to the untrained eye, it is obvious that the brain of the football player is nearly half the size of the hockey player's. While it's too early in the analysis to draw any scientific conclusions, the smaller size and general appearance of the football player's brain indicates something to Dr. McKee.

"I can say that he's got all the hallmarks of advanced CTE," she explained, turning the brain over in her hands. "He's got the shrinkage of the brain in general, the dilation of the spaces — the interior spaces — the big third ventricle, the smallness of the hippocampus, the absence of the septum."

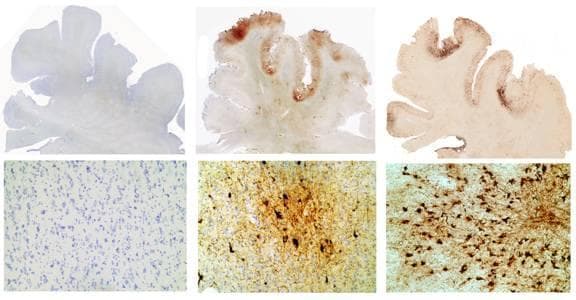

After Dr. McKee has examined the brains, researchers at the brain bank take selected portions, slice them thinly and lay them on slides for more detailed viewing. Specifically, Dr. McKee is looking for an abnormal protein called tau, which shows up in elevated levels in brains with CTE.

Results Too Serious To Ignore

Back in her office, Dr. McKee recalls the first time she saw that kind of protein build-up in a football player's brain. Back in 2008, when the center was just getting started, she examined the brain of John Grimsley, a former NFL player who accidentally shot himself while cleaning his gun. Describing Grimsley's symptoms now, it's remarkable how similar his story sounds to that of Dave Duerson.

"It turned out that his wife had been concerned about his condition for about five years," Dr. McKee said. "She noticed little things different about him — it was difficult to really put her finger on, but he just didn't seem quite like the guy she married. A little inattentive, more irritable, shorter fuse. And the real thing that she was noticing was memory loss."

So, after his death, Grimsley's wife donated his brain to the center. It was the first football player Dr. McKee had examined and she was astonished by what she found. The brain was so extremely degenerated that it looked as if it belonged to an 80- or 90-year-old, rather than someone half that age. "To see this in a 45-year-old was truly mindblowing," she said.

It was then Dr. McKee began to realize the extent of the damage that contact sports might be having on athletes. But it would be some time before the NFL would acknowledge the same. McKee recalls being frustrated by her first two meetings with the league, the first being in May of 2008. "I definitely had the feeling that my findings were falling on deaf ears," she said.

But after high-profile congressional hearings on the matter in October 2009, when NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell adamantly denied any link between brain damage and the repetitive concussions often suffered by his players, Dr. McKee was invited back — and this time the league was listening. About a month later, she was stunned when the NFL donated $1 million to the center's research.

So What Comes Next?

"I think the biggest problem for football is going to be: How do we deal with those sub-concussive hits, those thousands of hits that occur just in the course of a single year, just from the way the game is played?" Dr. McKee said. "That's going to require serious rule changes and that's going to be very difficult for not just the football league to accept, I think it's going to be very hard for fans to accept."

As a lifelong football fan herself, Dr. McKee doesn't pretend it's going to be easy and she doesn't claim to have the answers. She is leaving that to the leagues to figure out, though she does say that she thinks developments in equipment — such as better helmets — cannot alone solve the problem.

"If you think about it, our brain is floating in fluid and our skull in a way is nature's helmet, it's this hard protective covering so that when we experience a hit to the brain we don't injure our brain," she explained. "But because it's in this fluid, when we're going very quickly forward and backward, acceleration and deceleration, the inertial forces are being acted on the brain — helmet or not."

Knowing all of this, it's probably not suprising that Dr. McKee has a hard time enjoying herself when she watches football these days. "Ignorance is bliss," she said. "It's tough now. Watching the game, I can still really enjoy it, but I have to put my other self on hold in order to do it."

Earlier CTE Coverage:

This program aired on May 4, 2011.