Advertisement

White's Busing Legacy His 'Biggest Blemish,' Says Former City Councilor

Resume

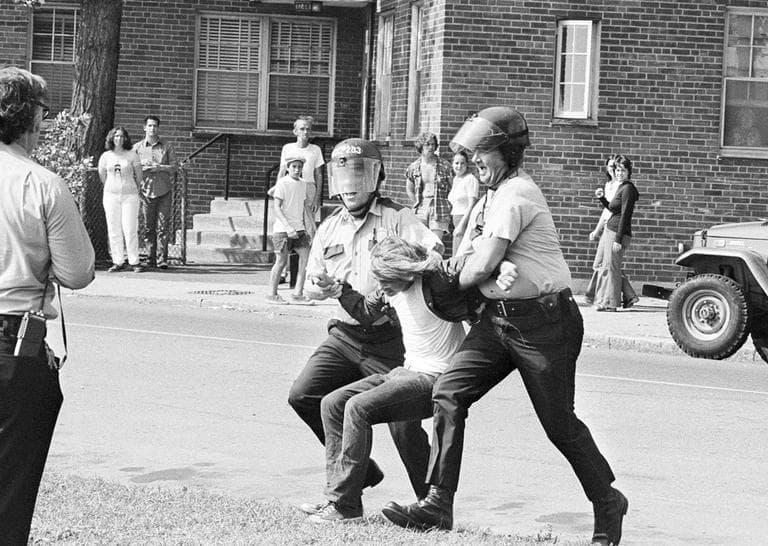

Most remembrances of the late Boston Mayor Kevin White, who died Friday, focus on how he helped physically transform downtown Boston. But White's four-term tenure also included one of the most difficult chapters in Boston history: court-ordered school desegregation.

Emotions from that period are still so tense that several African-American leaders in the city declined to talk publicly about White over the weekend.

But one who did is Bruce Bolling, the first black president of Boston City Council. Before Bolling was elected a city councilor in 1981, he worked in White's administration. WBUR's All Things Considered host Sacha Pfeiffer spoke with him Monday about the mayor's legacy when it comes to forced busing of school children and race relations.

Bruce Bolling: I think that would be his biggest blemish, and that made a indelible impression nationwide of giving the impression of Boston as being a very racist and violent city. The established institutions — the City Council, the School Committee, the mayor, the business community, the philanthropic community, the religious community — no one weighed in in any responsible way to address this issue of school desegregation.

So what do you think Kevin White, as mayor of the time, could have done — given that that's the situation he faced — to try to make it less disastrous?

Well, the proverbial horse was already out of the barn at that point. I'm not so sure what else could have been done when you had a total abandonment of leadership in the city at the highest levels to deal with this issue. Then you had to implement the plan, and then you were dealing with the most visceral, emotional reactions in enforcing the plan. So the city went through a lot of trauma that, in my opinion, could have been avoided.

I spoke earlier today to Mel King, the longtime African-American community activist in Boston. He said that most politicians in Boston at the time, with very few exceptions, White included, were more interested in dealing with white anger than with the needs of the city overall, and that what people like White should have done was be out there in the streets in every community talking to people and trying to bring them together. Do you think that White could have and should have played that role?

That's a role that I think he did play at some level. Some would contend that it wasn't broad enough and it wasn't sustainable. And there may be some validity to that. But he was pretty much acting in a vacuum. And what I mean by that is that he was on his own, because he didn't have the support of the School Committee or the City Council at the time. Bill Bulger was an infamous opponent. Louise Day Hicks was probably the spokesperson and leading individual in opposition to the school desegregation process. So the mayor had no allies.

As we've heard much of over the past few days, White is credited for having brought major development to downtown Boston — Faneuil Hall, for example. But his successor, Ray Flynn, has been called more of a neighborhood mayor. How do you think that White's policies surrounding neighborhood development affected inner-city neighborhoods?

I think that the underpinnings of neighborhood development very much started with Kevin White. They were in their early, formative stages, and Ray Flynn picked up the mantle in terms of having a much more focused emphasis on neighborhood development. But when you look at the Model Cities program, you look at the development of the neighborhood health centers, community health centers — all of that started under Kevin White. When you look at the [Little City Hall] program and you look at how government could be closer to the people, those things were initiatives that were driven by the Kevin White administration. So, yes, he had a significant focus on large-scale economic development downtown, which transformed the city in a very, very positive way. But there was also neighborhood development elements being laid, as well, that were then championed when Ray Flynn became mayor.

This program aired on January 30, 2012.