Advertisement

On Milestone Anniversary, Boston Recalls Its Abolitionists

ResumeSaturday marks a milestone in the fight for racial equality in the United States.

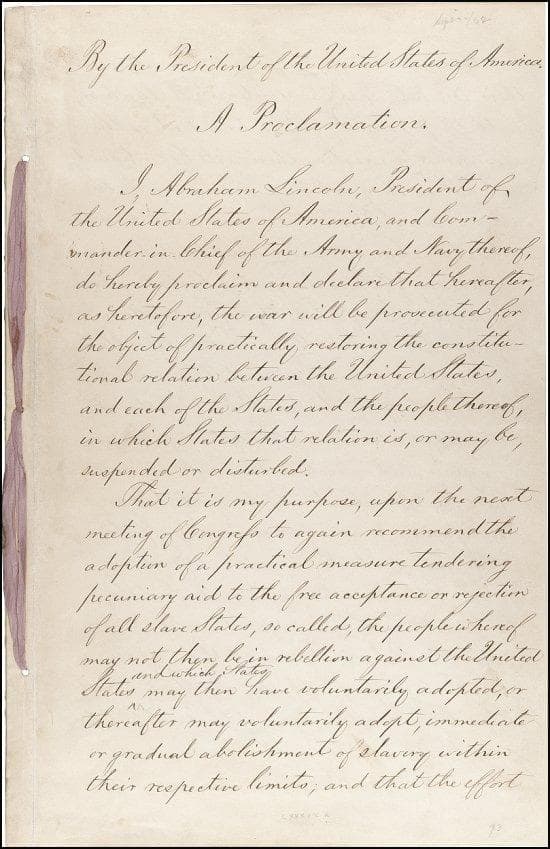

It was on this day 150 years ago that President Abraham Lincoln signed his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation — the first official step toward the abolition of slavery in the U.S.

Boston's historic African Meeting House, the oldest extant black church in America, is where leaders of the Abolitionist movement gathered to plot their course of action to bring an end to slavery.

Their efforts got a moral boost from Lincoln on Sept. 22, 1862, when the Civil War was more than a year old.

"The president by mid-July had decided that he is going to issue the Emancipation Proclamation," said Beverly Morgan-Welch, the executive director of the Museum of African-American History. "He is issuing this proclamation 100 days before Jan. 1, 1863 — basically let it be known if by Jan. 1 you're in a state of rebellion, we're going to free all of those enslaved."

Morgan-Welch says it was a strategic move.

"Lincoln makes it very clear that his position is to preserve the union," she said. "This is about moving the war effort forward, this is about winning the war."

One hundred days later, with the war still ongoing, Lincoln issued the final proclamation.

"He's not freeing everyone," Morgan-Welch said. "He wants to keep the border states that still have people enslaved in the fold. That's strategic. He's not saying that he doesn't believe in slavery as an institution. And in fact he believes that because there are black and white people this is pretty much always going to be a problem."

Brookline native Stephen Kantrowitz is a University of Wisconsin historian who spoke this week as part of commemorations at the African Meeting House in Boston. His new book chronicles the struggle to abolish slavery through the lives of black activists in and around Boston who were still fighting for full citizenship even after the legal end of slavery.

"There was a concerted campaign that persisted through the Civil War and never stopped afterward," Kantrowitz said. It was a campaign, Kantrowitz says, that deliberately perpetuated the legacies of slavery.

"And it's the success of that campaign that we continue to live with," he said, "this in some ways the elements of a caste society in the United States."

Some, such as Boston historian Bob Hayden, see this struggle continuing today.

"This is an ongoing, constant, never-ending challenge to educate people around the issues," Hayden said. "Just look at voter suppression that's being attempted in a half dozen or more states. They call it voter suppression with the requirements that some states are trying very hard to implement, to reduce people in certain parts of the country from voting. I think people need to know that's going on and understand what that means."

Events this week are just the beginning of a campaign that continues into next year, commemorating the Emancipation Proclamation and the long citizenship fight that followed.

"The fact of the matter is that it is everyday people, everyday citizens who make freedom rise," Morgan-Welch said.

And Morgan-Welch says it's only fitting that much of the focus is on abolition activists here in Boston.

"Lincoln himself says that Boston had done more to bring on the war than any other city," she said.

This program aired on September 22, 2012.