Advertisement

Efficiency Expert: Andrea Zittel Talks About Her Art Of Living

“I think it’s really hard being an artist now because we’ve been educated in every belief of every artist that came before us and told they were wrong. … I really want to believe in something.”—Andrea Zittel

Andrea Zittel’s art can bring to mind space capsules and bomb shelters, Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Concord's Walden Pond and Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes. Under the banner of her one-woman “A-Z Administrative Services,” she’s bred chickens, designed uniforms for everyday wear (literally), constructed Scandinavian Modernist-looking living units devised to squeeze every last inch of useable space out of an apartment, and built her own island.

“Originally I didn’t even like Modern design,” the California artist said during at talk at Boston University’s Morse Auditorium on April 3. Her projects are “Whole Earth Catalog” earnest, but also funny, strange, embodied critiques of American life. All part, she writes, of an “ongoing endeavor to better understand human nature and the social construction of needs.”

In them, you can sense both the New York apartment dwellers’ quest for the most efficient use of their tiny homes as well as the Western pioneer’s (or religious visionary’s) notion of heading out into the desert to devise new spare, utopian, futuristic ways of living.

“Rules make us more creative,” she told the BU audience. More comments from her speech follow below.

In the early 1990s, Zittel rented a $300-per-month storefront in Brooklyn, where she lived, bred chickens, and built special breeding habitats for the fowl.

- “I started to become really conscious of the structure of my own life.”

- “I realized that their lives were so much better organized than my own. And just as a personal project, I decided I should do the same with my own.”

- “When you’re a girl and you grow up in southern California, you’re sort of brainwashed to think that [fashion] variety equals freedom.”

- “There’s a sort of moral rule that you don’t wear the same dress twice.”

Instead in 1991, she began making her “Six Month Uniforms,” plain black dresses that fit in well at her art gallery day job, and that she wore everyday for six months at a time. (Later versions pictured at top.)

- “My boss looked at me almost at the very end and asked me if I’d worn that dress the day before.”

In 1994, Zittel bought Brooklyn building that she subsequently dubbed “A-Z East.”

- “I made furniture and lived with it. And when I needed a change, I’d sell the whole set and make a new one.”

- “When I made ‘Pit Bed’ [a soft bowl of a bed set in a wood-decked frame], I was concerned that my work was not comfortable enough. … My furniture was not comfortable. And I was trying to figure out what the difference was. I decided that inside-of furniture was more comfortable than on-top-of furniture. And I was making on-top-of furniture.”

- “In 1998, I fell in love and very spontaneously decided to pack everything up and move to L.A.”

- “He was not fat, but he was large. He would sit on things and break them. I pretty much had my whole thing figured out as an artist. And it all came crashing down. I couldn’t ‘A-Z’ my boyfriend.”

- “I was always trying to correct myself. I was always trying to create these structures that improved us somehow. I started to embrace human imperfection.”

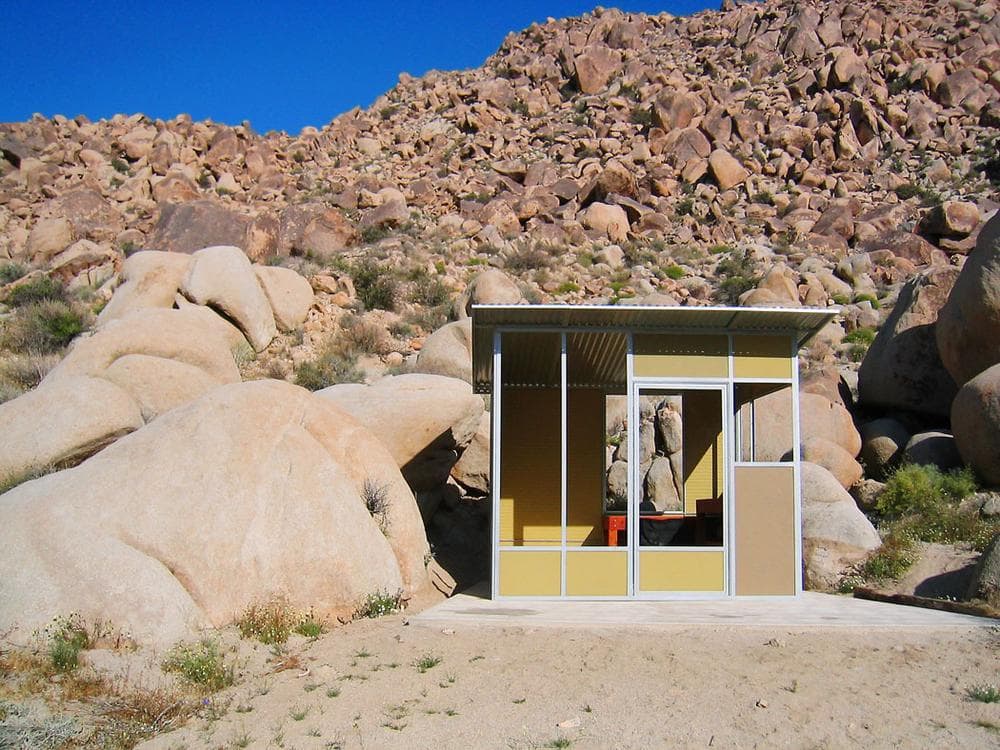

In 1999, she moved out to 1940s homesteader house near Joshua Tree National Park in California, where she began developing “A-Z West,” a “testing grounds” for her “designs for living.”

- “I believe most people are drawn to the desert in search of some kind of freedom.”

- “The motive of ‘A-Z West’ was to make a place where work can be born, live and die in a single location. … Instead of making my art feel more real, my life started to feel more staged and artificial.”

- “I began to think of art less as an imitation of life and more as a conduit through which life can function.”

- “It’s always very hard to get collectors to customize my work. My friends had absolutely no problems cutting them up and transforming them.”

- “I don’t know what I believe in that is big. But I’d try to put together every little thing I knew and maybe over time they’d add up to something big.”

- “I really felt like everything that is wrong about California is what I loved and what inspired my work. … In California, everything is getting more and more built up all the time. And I kept wondering what would happen when we ran out of space.”

Her (sort-of) solution was to construct “A-Z Pocket Property” in 1999, a 54-foot-long concrete island floating off Denmark.

- “I find I’m really drawn to the idea of the island because it represents individuality and autonomy.”

- “I was really young and I read a book about house boats. And I thought, ‘Yeah, I can make a 54-ton island.’ … It was really hard making a piece that big.”

- “It became clear that there was no way I could take care of this.”

- “I was always kind of depressed that we had to destroy that island. I’ve had these fantasies of recreating it.”

In 2010, she did—a smaller fiberglass and foam cabin-island floating on a lake connected to the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Andrea Zittel's "A-Z 2001 Homestead Unit II from A-Z West with Raugh Furniture." (Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, copyright Zittel)

For a 1998 show at New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery, she exhibited her “Raugh Furniture,” a couch-thing resembling a rocky hill and made out of delicate (too delicate, it turned out) foam. At exhibit opening, she had naked people sitting on the thing—thinking this would scare others off from joining them. "If you tell people not to get on something that’s made to be used they think you’re a fascist,” she quips. Instead, guests stripped off their own clothes and climbed on.

- “So we ended up with this whole crowd of drunken naked people on the foam. And they completely destroyed it. And it took me years to pay off. I don’t know that there’s any moral in that.”

Then for a week in 2000, Zittel sealed herself up in a Berlin studio without any clocks or access to daylight for her "Free Running Rhythms and Patterns” project.

- “I’ve always been really interested in how constructed our sense of time is. … I was always really interested in what it meant to live without time.”

- “I’m always really interested in this fine line between freedom and restriction. In this one, I was emancipated by putting restrictions on myself.”

- “At a certain point in the experiment I started to run out of food. It wasn’t a total tragedy because I had a stockpile of beer.”

- “It’s really important that my work results in some real lived experience. I’m trying to figure out if it’s enough to have it myself or it I need to share it with others.”

- “I would like to think that I’d do what I do whether I have an audience or not. Because it goes back to having an authentic experience.”

- “I hate my work. Personally I think every good artist is filled with self-doubt. I meet artists who aren’t and it’s so weird. … Because that’s what fuels everything, right?”

This article was originally published on April 08, 2013.

This program aired on April 8, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.