Advertisement

'She Who Tells A Story': Photos Show The Middle East Through Women's Eyes

For decades, the Middle East was an Orientalist's fantasy, home to the Holy Land and harems. Eventually, that fiction gave way, and nowadays the Middle East is a war zone reality, home to tyrants and violence.

But for Kristen Gresh, curator of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, neither one of those perceptions is entirely accurate.

Gresh says the Middle East is a mosaic of cultures, full of provocative, contemporary photography — most of it coming from women. But that's not a story we hear in the United States, she says.

So Gresh is trying to fix that with a new exhibit: "She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World."

The show is the first of its kind in the U.S. It includes photographs from 12 female artists across the Arab world and Iran, offering an insider's look at an often-misunderstood region.

"I hope that it will help people to understand the region in a better way," Gresh said, "if not just to simply provide another perspective from what we're hearing on the radio in the morning and seeing on television."

Gresh says the exhibit is a chance to privilege art above politics.

Some of the photos deal with war, but many of the images deconstruct identities and confront Orientalism.

“I needed to understand what makes us Arab women so different in the eyes of the West."

As soon as you walk in the doors of the Foster Gallery at the MFA, you see Lalla Essaydi's triptych. A woman lying on a divan is intently gazing at you. She's gilded and glittery. Then you step closer and realize that all that glitters is not gold. It's bullets.

The woman is decorated with shell casings. She's wearing hospital gauze with henna calligraphy tattooed all over her body.

Essaydi says the photos were a response to the revolutions that rolled through the region in 2011.

"During the time of the Arab Spring, at the beginning, I was so enchanted how women were at the forefront of everything," Essaydi said. "And then once the [new] governments were in place, the first rule they want is to put women back again."

The anger directed at women triggered a reaction from Essaydi.

"My response to it is to use something that is so beautiful but when you think about it is really significant of violence, and violence on women to protect the domestic space," she said.

For Essaydi, women were casualties of the Arab Spring, but rather than make that point through pictures that are painful to look at, she uses beauty to draw people in. Her sense of aesthetics has its roots in Orientalist artwork, which she says has inspired much of her photography.

"I needed to understand what makes us Arab women so different in the eyes of the West," she said.

Essaydi was born and raised in Morocco. She lived in Boston in the mid-1990s and graduated from the MFA's Museum School. She says she was drawn to photography by exploring her own personal Arab identity.

"I have this love-hate relationship with the Orientalist painting," she said. "I always thought that, you know, it's a fantasy — it just shows these women walking around naked, doing nothing, but I had no idea people believed it was truth."

The question of identity is central to another artist in the exhibit with local roots. Rania Matar grew up in Lebanon and now lives in Brookline.

Matar took a series of photos called "A Girl and Her Room;" the collection includes pictures of teenage girls in the Northeast juxtaposed against photos of girls in the Middle East, all in their bedrooms. (The MFA show only includes her photos from the Arab world; you can see how all the photos look side-by-side at her website.)

Matar says she chose the bedroom as a studio because it was personal.

"It was like the girls had one room they could control, and it was their bedroom, and it was kind of where they were looking for the identity in who they are," she said.

Matar says one of her favorite images from the series is a photo of a young woman named Christilla; she likes it because it keeps people guessing.

"(Christilla) is like a fake blond — beautiful, young woman, sitting in her chair, with a big poster of Marilyn Monroe behind her," Matar said, describing the picture.

The photo was taken in a suburb of Beirut, but, from Matar's perspective, you can't tell.

"I mean, here she is wearing green Crocs, she has a pink bra hanging," Matar said. "Her whole attitude is typical of a teenage girl."

She says after 9/11, there was so much talk about the contrasts between the Middle East and the U.S. But for her, girls everywhere are the same — they're navigating teen life, trying to figure out how they want the world to see them.

"This for me, maybe it's almost biographical," Matar said of her series. "I'm the one straddling these two cultures. And, for me, they're not so different."

Identity is central to most of the photography in this exhibit, and sometimes that identity inevitably comes in the form of the hijab (the Islamic head scarf) or the niqab (the face veil).

One artist — Bushra Almutawakel, from Yemen — simultaneously defends and critiques the veil in her work. She has a series called "Mother, Daughter, Doll," which is comprised of nine images of herself, her daughter and her doll. They look like studio portraits.

"Coming from Yemen, that’s normally how I dress — the first photo, a coat and a scarf," Almutawakel explained.

Her clothes are colorful, her daughter's hair is uncovered; they're smiling. In each passing photo, their smiles fade and they're veiled under more layers of clothing. The final photo is entirely black.

"One of the things that I noticed over the past 10 years, there’s an extreme type of Islam that you see more and more prevalent throughout Yemen," Almutawkel said. "And, one of the ways that you see it is how women are covered. It didn’t make sense to me, and I felt it had nothing to do with Islam."

She says the images are a critique of her society.

"You want to fix something or change something, you’ve got to at least talk about it, or at least acknowledge that it exists," Almutawakel said.

Newsha Tavakolian also uses photography as a mirror to her society, though in a different context: Tavakolian is a photojournalist in Iran.

Her work has appeared in The New York Times and Time magazine. Tavakolian normally takes photos of news events, but a couple of years ago, her press card was temporarily revoked by the government. So, she says, she had to figure out another way to indirectly tell the story.

"We have a saying when they take your nose, you cannot breathe through your nose, you don't die," Tavakolian said. "You open your mouth, and start breathing through your mouth."

For Tavakolian, art photography became her new way of breathing.

"In art photography, you can be vague," she said. "You don’t need to have clarity, you can show everything in different ways. And, the thing is, that’s why many young people, they’re very interested to do art because they can talk about their subject but don't get into trouble."

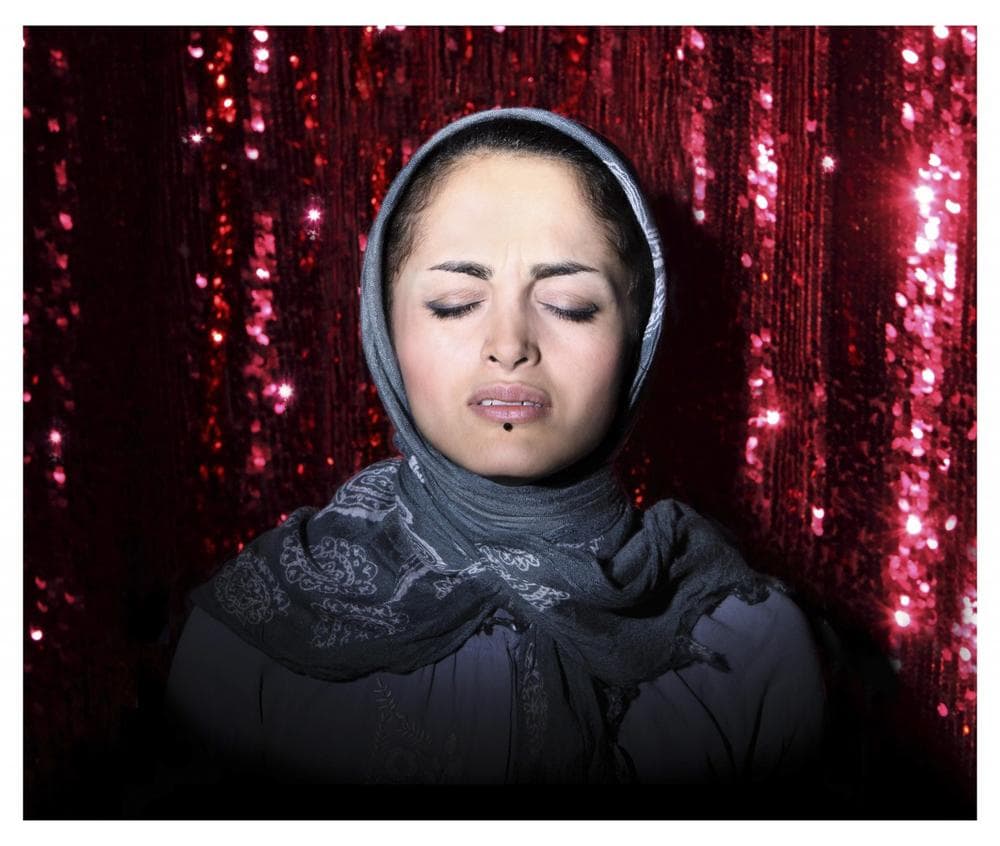

Tavakolian's focus is the plight of women singers in Iran, who are not allowed to perform solo in public. Her series, “Listen,” includes six portraits of Iranian singers against a shiny, glittery backdrop. Each woman has her eyes closed, her mouth open, as if in the middle of a refrain.

Tavakolian also created imaginary CD covers for them, because they’ve never had CDs, and a mute video installation, where you can watch the women sing, but not hear their voices.

Tavakolian says she wants to bring attention to issues, but not tell people what to think.

"I mean I just want to show things, I don’t want to convince anybody to think different," she said. "The thing is I grow up in a country where it’s based on ideology. So, I never forced anybody, I just show people. If they want, they can think. If not, they can just look at it and leave."

For Tavakolian, fine art photography was a way to survive when her press card was taken away.

But for Rula Halawani, from Jerusalem, it was a choice.

"It was very hard for me to do photojournalism because I couldn't keep my feelings on the side and just take pictures of funerals, women grieving," Halawani said. "It was so hard for me to just act like I am not part of the story. You know, like end of the day, I'm part of the story and the story is part of me."

Halawani was a photojournalist for the Reuters news service, but she says she quit the day she saw a young Palestinian boy she knew shot for throwing stones at an Israeli soldier.

"I felt like me and my cameras are not doing anything," she said, recalling the incident.

In 2002, when the Israelis invaded the West Bank, Halawani took to the streets to photograph the tanks, the soldiers, the destruction. Those photos are hanging on the wall at the MFA — a sort of surrealist take on the news.

She calls the collection of images the "Negative Incursion" because she transferred the pictures into their negative original form.

"And, at the same time, the whole situation was so negative to me," Halawani said. "You know, before the negative incursion, I was for peace, and I was for the peace process. But when I experienced this situation, I felt so negative about peace."

Halawani says the images also look timeless and dark; people can't tell if they're from 2002 or 1967. She says she saw the violence erupting at night, and she wants visitors to empathize with how she felt taking the photographs in the dark at night.

"The world is sick and tired of looking every day that somebody's dead in the newspaper," Halawani said. "I wanted to find a way that people will look at the situation in more depth."

Overall, the MFA exhibit includes artwork from 12 photographers. The show is diverse thematically and geographically, covering some 3,000 miles from Iran to Morocco.

But together the photos have a collective mission.

At a recent symposium to celebrate the exhibition, Queen Noor of Jordan made the point that for so long women of this region have had others tell their stories — men, the West, the media. This exhibit offers Middle Eastern women a chance to finally tell their own stories by subtly critiquing those other narratives.

"She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World" runs through Jan. 12, 2014.

Listen to the audio version of this story below:

This program aired on October 9, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.