Advertisement

After Triumph Of ‘Snow White,’ How Did Disney’s Artistic Reputation Collapse?

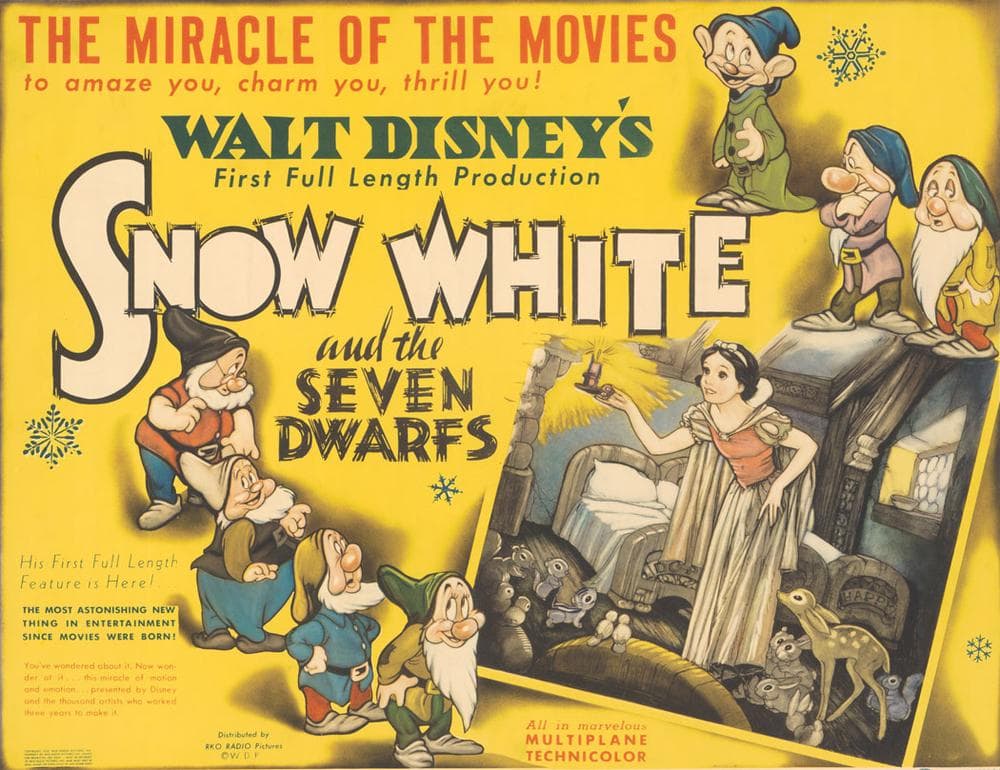

It’s hard to overestimate the success "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” the Walt Disney Studios’ landmark first feature-length animated film, had when it opened for Christmas 1937.

“It is a classic, as important cinematically as ‘The Birth of a Nation,” The New York Times gushed. The New Republic proclaimed: “Among the genuine artistic achievements of this country.” Cecil B. DeMille telegrammed: “I wish I could make pictures like ‘Snow White.’” Harvard and Yale gave Disney honorary degrees.

Audiences agreed, making it the highest grossing film in history, to that point, Neal Gabler reports in his 2006 biography “Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination.”

So how did today’s “sophisticated” take on Disney himself and his company come to be: sentimental, manipulative pap designed to sell crap to kids?

“Snow White” and, oh, its songs by Frank Churchill and Leigh Harline—“Whistle While You Work,” “Heigh-Ho,” “Some Day My Prince Will Come”— continue to resonate nearly 76 years after its debut. As is evident in the exhibit “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: The Creation of a Classic,” on view at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, through Oct. 27. Originally organized by Lella Smith, creative director for the company’s Animation Research Library, for the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco, it features more than 200 artworks drawn from Disney company archives.

You know the story (uh, spoiler alert?): Queen is threatened by the good looks of her stepdaughter, orders her killed, hitman can't do it, sends young Snow White off to escape through creepy forest, she finds haven among woodland animals and in the cottage of seven dwarf diamond miners, Queen discovers Snow White lives, magically disguises herself as old crone, tricks Snow White into eating poisoned apple that puts her into coma, dwarfs fight and defeat Queen, handsome prince’s kiss awakes Snow White, happily ever after.

At root, the film is two mirrored tales—the adolescent girl running away from her family to become an adult; the middle-aged stepmom terrified that her looks are going, that she’s getting old, and willing to do anything to hold back the advance of time.

The film signals its aesthetic ambitions by spending its opening sequences focusing on realistically depicted humans and pigeons that flutter down around Snow White as she sings to her reflection in the bottom of well about wishing for love. It’s only when she runs away into the forest that the critters become cartoony and she meets the more caricatured dwarfs.

“Snow White” was the filmmaking equivalent of the space race that the United States entered between 1957, when the Soviets launched Sputnik, and 1969, when Neil Armstrong made one small step onto the moon. What had seemed like a crazy fantasy a decade before, had—through the combined efforts and ingenuity of hundreds of people and a rocketload of money—become reality.

Similarly between 1934 and ’38, Disney studio staff more than doubled, topping 600 people as it geared up to launch cartoons into the stratosphere. The crew’s aesthetic advances are on view at the Rockwell Museum. The exhibit includes animation cels—final cartoon drawings painted on clear celluloid acetate which were usually photographed, one movement after the next, atop watercolor backgrounds—but most of these are recent recreations based on vintage “Snow White” drawings, and they feel not quite up to the talent of the 1930s artists. Where the studio’s excellence is on display is in surviving, original studies and background paintings for the film.

Grim Natwick, a cartoonist hired away from Fleischer Studios where he drew Betty Boop because Disney folks figured he had a way for drawing women, gives “Snow White” a Boop-ish big head and sexuality in early designs—a style that was soon abandoned. The show also includes sketches of Snow White in a wedding dress floating in the clouds for a sequence cut from the film.

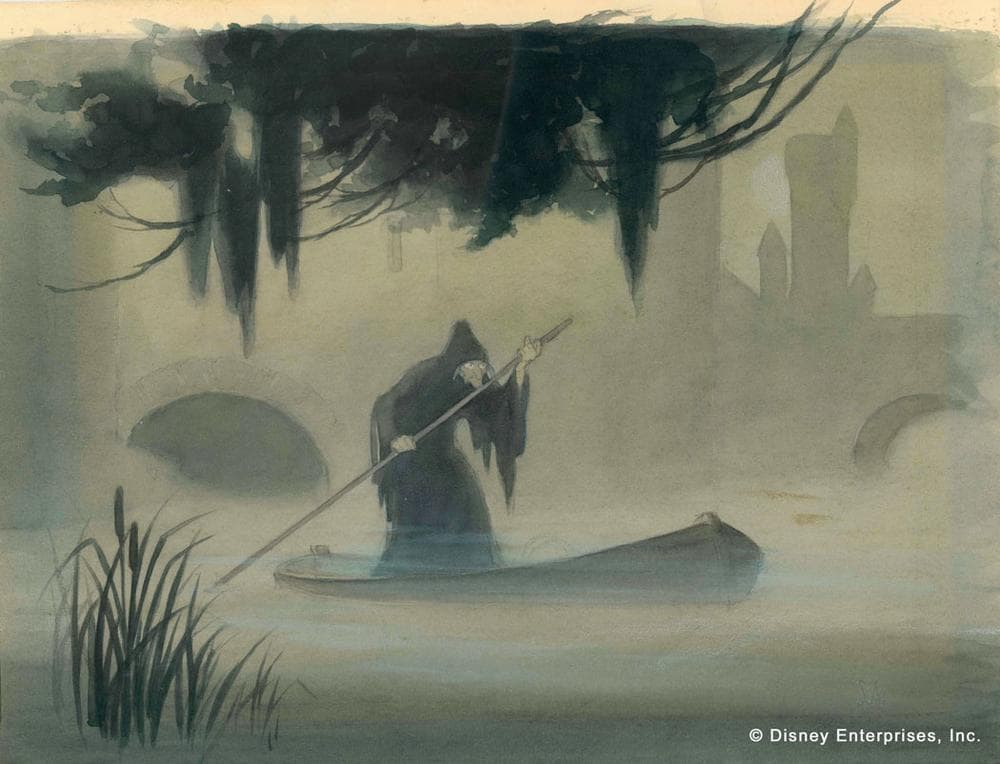

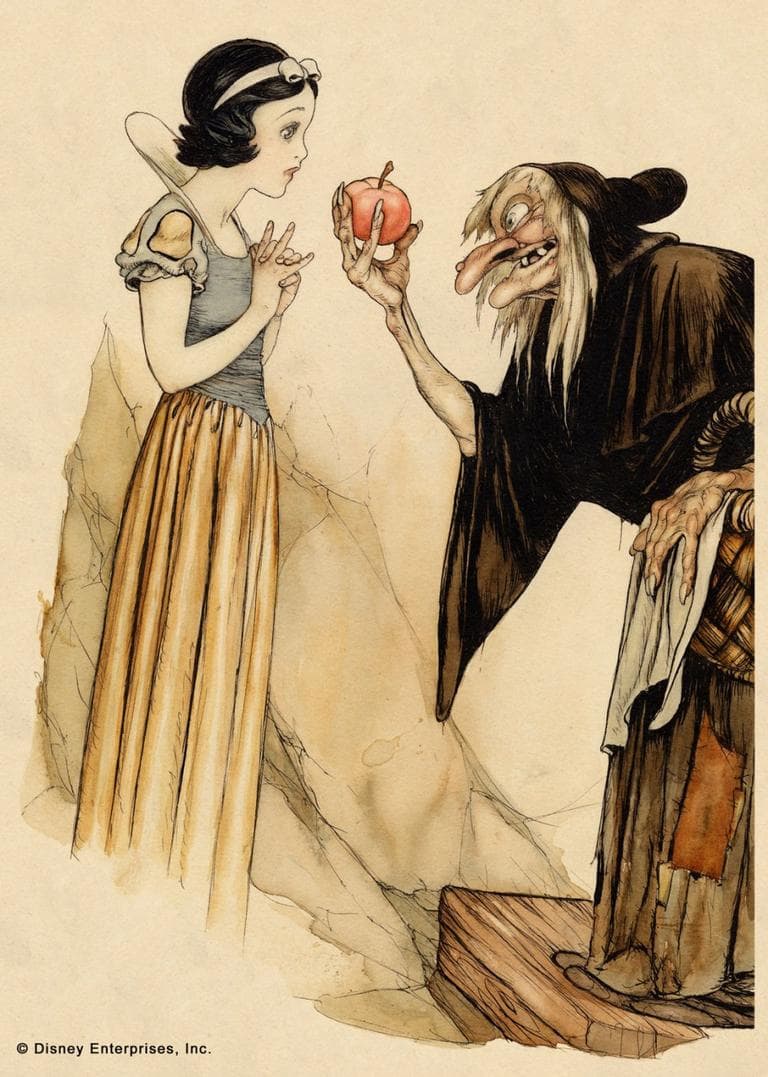

Instead the film moved more toward the style of Gustaf Tenggren, a Swedish-born illustrator now best known for the 1942 Little Golden Book “The Poky Little Puppy.” He brought an Old World fairy tale look to watercolor studies like one here of the crone offering the poisoned apple to a wary but curious Snow White. The witch is more gnarly and Snow White more delicate than in the final film, but you can recognize the foundations of the film’s tone.

Some of the most extraordinary artworks are background paintings for the film—like a terrific pencil and watercolor rendering of the Dwarfs’ cottage in the woods, decorated with elaborate details of woodwork. Elsewhere Maurice Noble, who went on to do major work on Warner Bros. Bugs Bunny cartoons, contributes a watercolor study for the cottage interior including a wood chair with a back carved like an owl.

See how the artists use light to energize scenes—as in sketches of Snow White exploring the Dwarfs’ cottage while holding a candle or the Dwarfs marching across a log-bridge silhouetted by the setting sun. Black and white pencil and watercolor sketches by Ken O’Connor working out the final mountain top confrontation between the Queen and Dwarfs are electric with the drama of the chase, of the rain, of the great rocky heights, of the lightning bolt that does the witch in.

“Snow White” represents a miraculous advance in animated technology and performance, though Snow White herself remains mainly a stock damsel in distress. Just a decade earlier in 1928, the Disney studio had debuted a black and white cartoon—one of the first cartoons with synchronized sound—about a rascally, charismatic, musical, action hero rodent called Mickey Mouse. He was little more than a stick figure, so simple that the first Mickey cartoons could be drawn nearly entirely by one man, Ub Iwerks.

Over a series of films over the next decade—“The Skeleton Dance,” “Flowers and Trees,” “The Old Mill”—the Disney crew mastered acting and synchronized sound and color with one milestone after the next. The cartoons were championed by the intelligentsia. Esquire magazine raved in 1937 that none of “dozens of works produced in America at the same time in all other arts can stand comparison with” Mickey’s first color cartoon, 1935’s “The Band Concert.” A bit of hyperbole, sure, but when the Art Institute of Chicago exhibited a 100 Disney drawings, the museum’s director told The New York Times in 1933 that they “constitute art in nearly every sense.” As Disney biographer Neal Gabler notes, classical conductor Arturo Toscanini invited Disney to visit him in Italy and pioneering Russian director Sergei Eisenstein sought to publish a book of Disney cartoon scenarios.

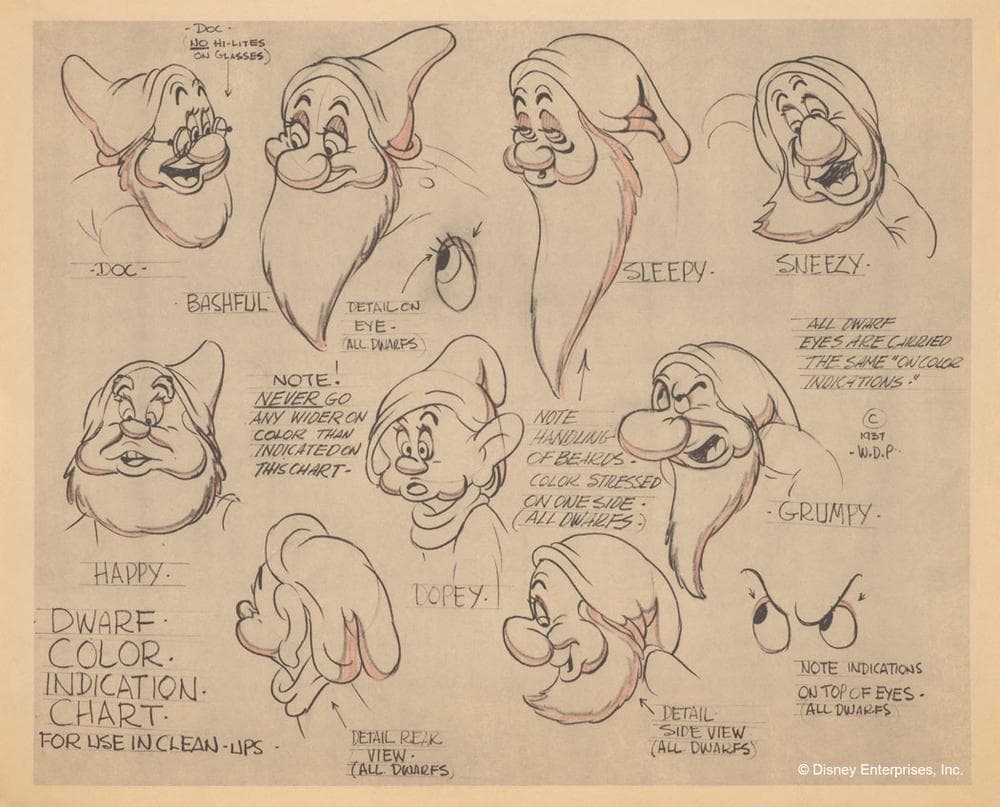

Now the Disney company focused on making the first full-length animated films with vividly realized human characters as well as music and dancing and comedy and pathos. Notice the buoyant, flowing movement in animation drawings here of birds hanging up Snow White’s cape in the cottage. One sign of the Disney artists’ achievement is easy to miss—rather than making the Seven Dwarfs a chorus of clones, they labored to give each an identifiable, different personality as indicated by their signpost names: Bashful, Dopey, Grumpy.

“Snow White” launched a remarkable string of Disney films between 1937 and ‘42—“Pinocchio,” “Fantasia,” “Dumbo,” “Bambi.” Hollywood may not have seen such a remarkable run of terrific work from one company until Pixar’s run of digitally animated features from 2003 to 2010—“Finding Nemo,” “The Incredibles,” “Cars,” “Ratatouille,” “Wall-E,” “Up,” “Toy Story 3.”

So when did Disney’s artistic reputation among highbrows collapse? Peg the shift to 1941 when a group of animators at Disney tried to unionize and Disney fought them tooth and nail, eventually provoking a strike.

Disney wanted to see the group as his family, who’d come through this great project together and revolutionized the field. He felt betrayed by the union’s complaints, like they were just in it for the money. Disney could motivate his people to great achievement, but he wasn’t an easy boss, and he didn’t seem to recognize that as the studio staff had ballooned in the ramp up for “Snow White,” it had changed from a small gang of pioneers to a large company of people, most excited to be there and devoted, but also (with reason) less willing to sacrifice their own income to the cause. Especially as “Snow White” raked in the dough.

The union fight caused Disney to be seen by a liberal-leaning art world as a politically conservative creature—which he ever more became, including joining an anti-communist group and testifying to the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee.

As a practical matter, the union’s eventual victory raised labor costs and, to Disney, made achieving the extraordinary artistry of his early feature films now seem financially unreachable. Then the studio was, in a way, drafted into making military training films for the government during World War II.

The upshot: Disney himself was alienated from his people and his films. In the following years, the company released feature-length compilations of animated shorts, but after “Bambi” in 1942, the company didn’t release another single-story, full-length animation until “Cinderella” in 1950. After spending a decade and a half pioneering animation as it has become known today and in the process producing an incredible string of feature-length masterpieces, Disney himself basically abandoned making big animated films. Subsequent Disney animated features seem to only occasionally have attracted his full, focused attention. Of course, his artistic reputation suffered.

Instead Disney turned his sights to nature documentaries, live-action films, early television, and then, his most enduring masterpiece, Disneyland.

This program aired on October 26, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.