Advertisement

Alice Hoffman Gives Voice To Ordinary People In Extraordinary Times

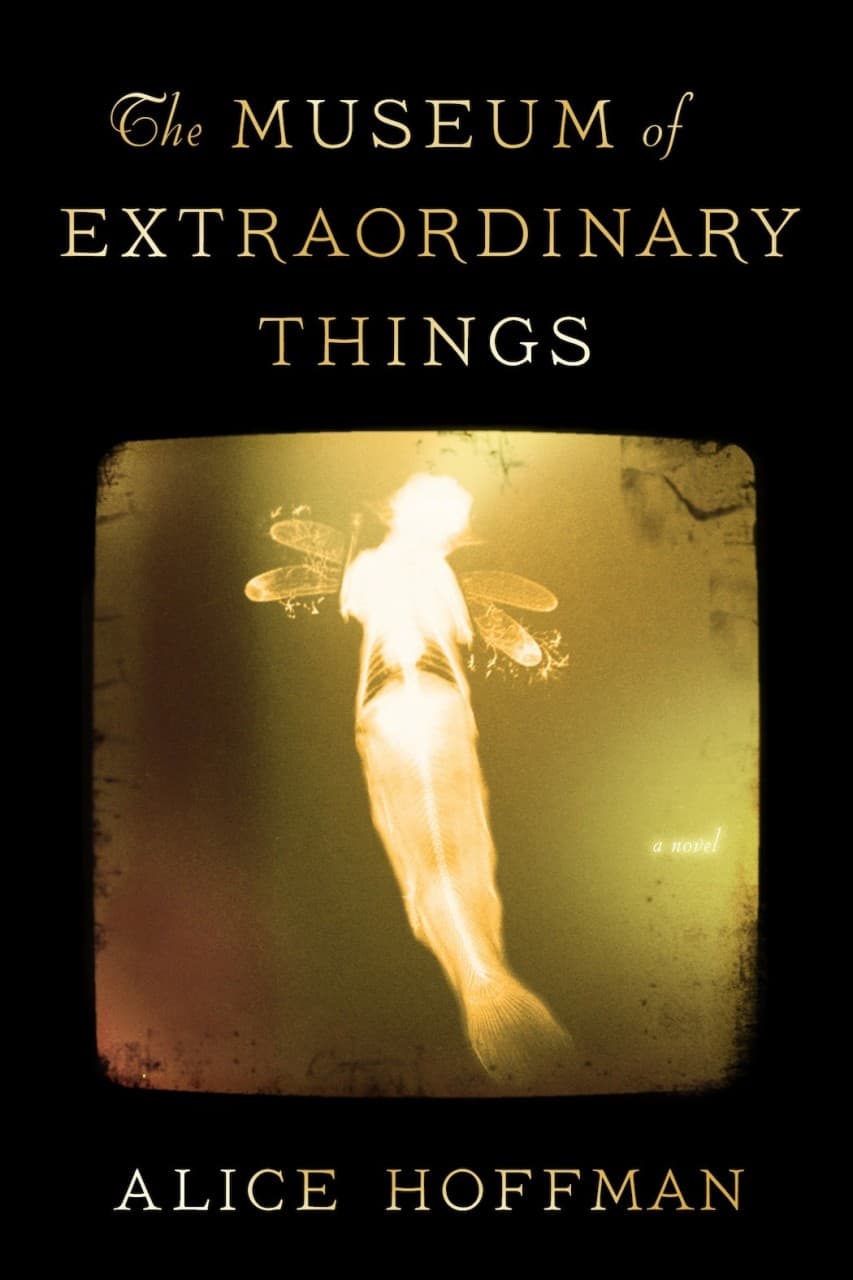

One thing’s for sure. Alice Hoffman knows how to tell a story. “The Museum of Extraordinary Things” takes us to the New York City of 1911 and centers us at a strange funhouse museum in which a professor — “part scientist, part magician” — parades his slightly disfigured daughter as a mermaid, along with the usual assortment of werewolves (a hairy man, actually), butterfly girls and other “living wonders.”

But this isn't Karen Russell territory. As we first enter the museum we seem to be in a world that’s part Ray Bradbury and part Steven Millhauser. How much of a fantastical tale will this be? As it turns out, the delicate balance between the everyday world and the extraordinary is balanced more in favor of the world we know, though not many writers describe that world as elegantly as Hoffman, author of "The Dovekeepers," does. (The Boston-based writer will be reading from “The Museum of Extraordinary Things” at Newtonville Books at 7 p.m. Tuesday.)

She’s also first-rate at describing the people who populate that world, particularly the three main characters — the professor; his daughter, Coralie; and Eddie, a young Jewish man who loses his faith when he thinks his orthodox father acted cowardly in the face of lethal union-breaking. They are each so vividly drawn that Hoffman’s cutting from one character to another, and her shifts from first person to third, feel just right. Not only don’t they wear out their welcome, they keep you lusting for the next development.

Lust? This isn’t “50 Shades of Grey.” In terms of good and evil, it’s almost black and white, somewhat reminiscent of Jayne Anne Phillips’ recent “Quiet Dell,” as these very modern writers create what seem like neo-Victorian, Dickensian morality tales, even drawing from historical events like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factor tragedy.

The lack of moral complexity is not all to the good in “The Museum.” The professor starts out as if there is a fair amount of gray in his character. He introduces Coralie to Shakespeare and Whitman and you wonder if it was the death of his wife that turned him into such a strict, joyless man.

But with every chapter the professor becomes more evil until he feels less like a tragic figure and more like a Gothic villain. The drama toward the end of the book turns a little too melo- as well. Hoffman didn’t have to stray quite as far from the novel’s naturalism to make her points about love in a time of cholera.

On the other hand, whether Coralie is Jane Eyre or Jane Austen heroine, she’s a delight. Her joys and sorrows are achingly felt whether it’s at the maltreatment by her father or the hope of a better life with a photographer she stumbles across — that would be our lapsed Jewish friend, Eddie.

He, in turn, is the most modern of Hoffman’s characters. His bitterness gives him an edge that provides heft to his gradual awakening to the humanity around him, which is grounded less in his relationship with Coralie than in the tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which he photographed. He was later hired to find a missing worker. Most of the 146 victims were young, Jewish or Italian female immigrants working in horrible conditions.

There’s a touch of “People’s History of the United States” to Hoffman’s world view, which she also ties together neatly with the personal narrative. Coralie brings the two threads together toward the end:

“I know we lived among extraordinary things but, perhaps more importantly, in extraordinary times … We no longer expected cruelty or mistreatment. We expected more.”

In her latest, Hoffman gives us extraordinary things and extraordinary times. And more.

More