Advertisement

Donna Tartt's Pulitzer Prize, The Marathon Bombing And A Secret Whisper

A bomb goes off in the unlikeliest of places. Bodies are everywhere. The effect of the loss of life for the survivors casts a pall, perhaps for the rest of their lives.

This isn’t the bombing at the Boston Marathon but at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It didn’t really happen, of course, but Donna Tartt’s description of it in her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “The Goldfinch,” highlighted the all-too-real Boston tragedy in an incredibly powerful way, even though it doesn’t really have anything to do with it.

It’s indicative of how art can touch the soul in unexpected ways, even in ways that the artist didn’t intend when she or he were creating the work in question. As she said in a New York Times interview, “Things will come to you and you’re not going to know exactly how they fit in. You have to trust in the way they all fit together, that your subconscious knows what you’re doing.”

Tartt was actually thinking of the Oklahoma City bombing when she was researching the novel as she needed to know what would happen in an interior space. Nevertheless, what Bostonian reading it today couldn’t think of what it would have been like to be in the middle of the Marathon mayhem last year when she writes through the voice of 13-year-old Theo Decker:

“In a cascade of grit, my hand on some not-quite vertical surface, I stood, wincing at the pain in my head. The tilt of the space where I was had a deep, innate wrongness. On one side, smoke and dust hung in a still, blanketed layer. On the other, a mass of shredded materials slanted down in a tangle, where the roof or ceiling should have been.

“My jaw hurt; my face and knees were cut; my mouth was like sandpaper. Blinking around at the chaos I saw a tennis shoe; drifts of crumbly matter, stained dark; a twisted aluminum walking stick.”

The really terrible discovery still awaits — his beloved mother had run back for a glimpse of Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson” and was killed in the explosion, set off by terrorists.

The loss is horrible enough. What drives Theo nearly mad, and what you hear so often in stories from last year’s Marathon victims and their families is the what/if exercise. Theo was out with his mother because he had been suspended from school and they were killing time before a meeting at the school.

What if he hadn’t misbehaved? What if the main culprit had come forward? What if they hadn’t gone to the Met? What if she hadn’t run back to Rembrandt?

Tartt paints as devastating a portrait of loss as you’d want to read, and you do want to read it because the writing is so exceptional:

“After I got off the telephone [the social worker implies but doesn’t confirm that his mother is dead], I sat very still for a long time. According to the clock on the stove, which I could see from where I sat, it was two-forty-five in the morning. Never had I been alone and awake at such an hour. The living room – normally so airy and open, buoyant with my mother’s presence – had shrunk to a cold, pale discomfort, like a vacation house in winter; fragile fabrics, scratchy sisal rug, paper lamp shades from Chinatown and the chairs too little and light. All the furniture seemed spindly, poised at a tiptoe nervousness.”

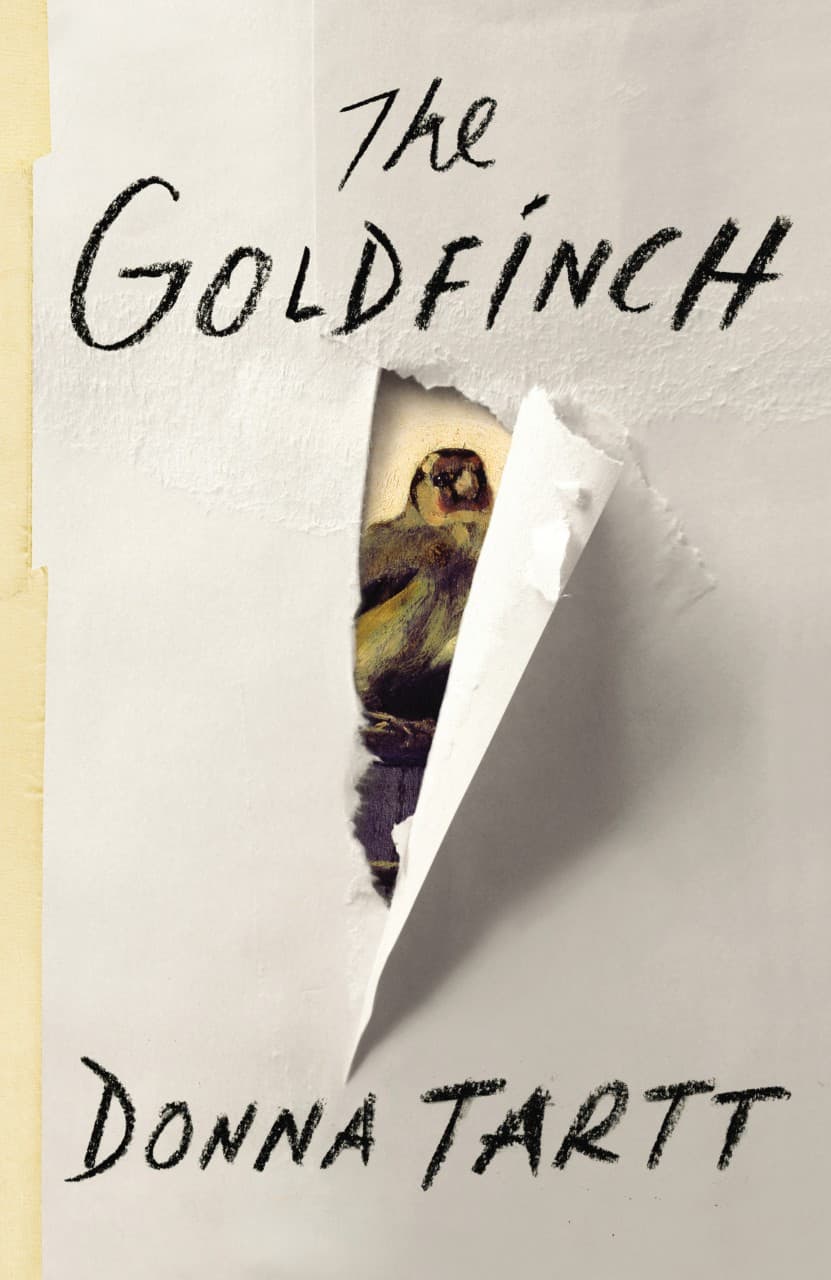

From here the novel takes on a Dickensian aura (and length). Theo lives for a while with his best friend’s family, his ne’er-do-well father in Las Vegas and a kindly antiques dealer (Hobie) who is the partner of a man in the bombing who, with his dying breath, told Theo to take “The Goldfinch,” by Fabritius, a 17th-century painter. Theo also becomes enamored of the young girl with the dying man, Pippa — a twist on Pip from “Great Expectations.”

It’s Theo’s story, not hers, though, as he tries in his own unguided way to find a set of values to live by following the senseless murder of his mother, his falling in with a best Artful Dodger friend from Russia who could eventually be a bit of an anarchist himself, his descent into nihilism, and of course his ownership of the stolen painting.

He’s told by a teacher:

“Well, from your essay, it seems as if you are drawn to … the metaphysical territory. Such as why do good people suffer … And is fate random. What your essay deals with is really not so much the cinematic aspect of De Sica[‘s “Bicycle Thief”] as the fundamental chaos and uncertainty of the world we live in.”

Tartt asks difficult questions of her readers, as well as her characters. There is no easy uplift in “The Goldfinch” and no easy resolution. Our own sympathies are questioned; our own responses to loss and devastation.

“The Goldfinch” is also about the place of art in our lives. What is a needless luxury to some and an investment to others is lifeblood to Theo, and to Tartt. And it isn’t the healing, or rational, or pro-social aspects of art that Tartt is writing about. It’s something much more mysterious, according to Hobie:

“If a painting really works down in your heart and changes the way you see, and think, and feel, you don’t think, ‘oh, I love this picture because it’s universal.’ ‘I love this painting because it speaks to all mankind.’ That’s not the reason anyone loves a piece of art. It’s a secret whisper from an alleyway. Psst, you. Hey kid. Yes you.”

Yes me, when it comes to “The Goldfinch.”