Advertisement

The Boston Bohemian And Walt Whitman — How American Rebels Got Their Voice

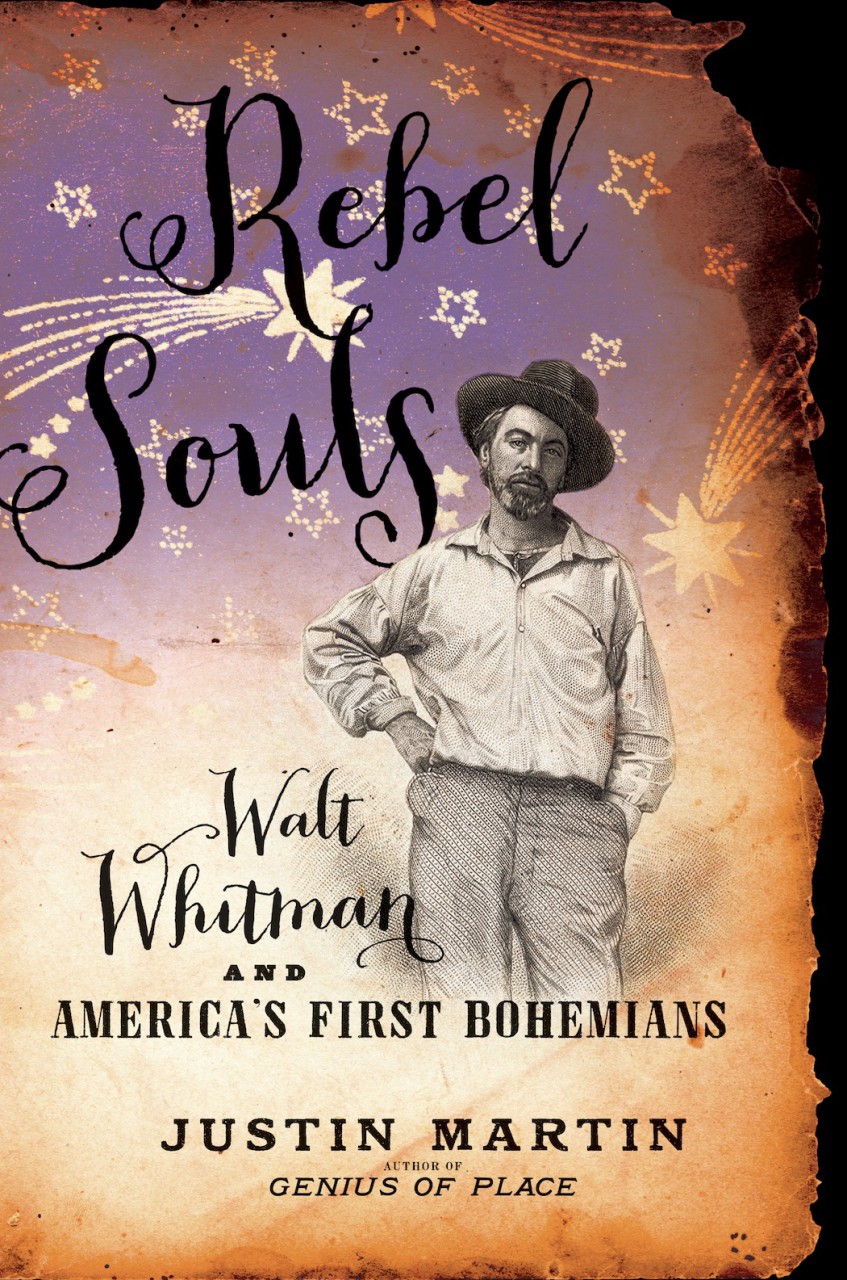

It’s rare for a book to conjure the feeling of being in a bar with one’s rowdiest and most interesting friends. "Rebel Souls: Walt Whitman and America’s First Bohemians" by Justin Martin (Da Capo Press, 339 pages) does just that, highlighting a group of daring individualists who helped shape American culture around the time of the Civil War and, for a time, had a ball doing so.

Martin takes us to New York City into a subterranean bar on Broadway called Pfaff’s, where at a long table beneath a vaulted ceiling a man named Henry Clapp Jr. brought together a group of “boozers, brawlers and barflies, journalists, comics, actors, artists and poets… to create a bohemian paradise.” Walt Whitman is among them, and it is his image that adorns the book’s jacket and his story that gives this narrative its heart and soul.

Martin is a journalist who’s previously tackled topics as diverse as Frederick Law Olmsted, Alan Greenspan and Ralph Nader. After a history professor asked Martin if he’d ever heard of Pfaff’s saloon, the author became intrigued and set upon a journey of discovery that resulted in the new book.

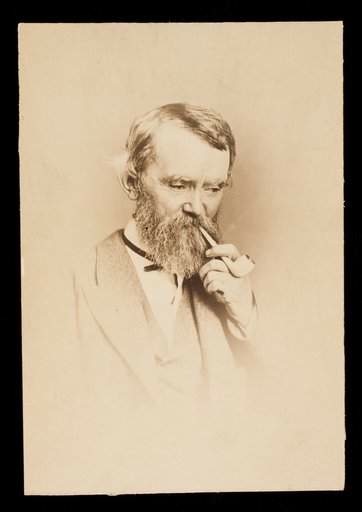

One could argue that bohemianism in America has its roots in Massachusetts. Clapp, a Nantucket native, born in 1814, whose family tree on both sides reached back several generations, is known as “The King of Bohemia.” After moving to Boston and working as a whale oil salesman, Clapp found his life’s calling of journalism after a neighbor asked for help putting together a death notice for the local paper. He worked for publications in Nantucket, New Bedford and Lynn, until he was sentenced to 60 days for libeling a justice of the peace. Clapp had already been well on his way to becoming a radical by then and in his 30s began giving lectures around New England, despite having, what Martin calls, a “shrill voice [that] was once described as sounding ‘like snapping glass under your heel.’”

Clapp would grow to hate his native region. If his life’s rebellion was against anything, it would have to be the strict Congregationalist upbringing and the Puritanical ways of New England, which he believed divided the world into the pure and the wicked. Ironically, Clapp would join the Washingtonian Total Abstinence Society, leading Martin to write, “The contours of Clapp’s character were starting to become evident. He was irreverent. He possessed a ready wit. And he was what today would be called a moral relativist.”

In 1849, Clapp traveled to Paris for a three-day world peace conference, arriving on the heels of an “incomplete” revolution that had nevertheless left the City of Lights humming with idealistic notions and its cafés filled with locals many dubbed eccentric or “free-living types,” at least by the standards of the day. Clapp spent enough time in Paris soaking up the scene with the so-called bohemians that when he returned to the States he headed not for Boston but New York City. He had a plan and he was looking for the right place to put it into action.

“As he settled into the life of the city, Clapp held fast to his idea of bringing Bohemia to America,” Martin writes. At 647 Broadway, a few doors north of Bleecker Street, he found the locus for his plan. Pfaff’s was a bar situated beneath a fancy hotel, marked only by faint lettering on the building and accessible via a hatchway in the sidewalk. Soon, Clapp and his growing cadre of new friends were rewarded for their patronage with a room of their own.

Martin gives us a different side of Whitman: A struggling poet trying to find his place both in the world and among a coterie of noisy fellow travelers. These fellow artists were some of the most interesting characters to haunt American letters and stages in the days just before, during and just after the war. Actor Edwin Booth, comic-writer Artemus Ward, author and drug imbiber Fitz Hugh Ludlow, and provocateur/actress Adah Menken are among them. Martin places them at Clapp’s raucous table at Pfaff’s just as fame is dawning for each, and then follows them through varied careers. Many would contribute to Clapp’s influential journal, The Saturday Press, and along the way they rub elbows with the likes of Mark Twain, President Lincoln and other artists, leaders and writers of the day.

The new bohemians suffer the highs and lows of their chosen lifestyle. Whitman struggles to get “Leaves of Grass” serious notice, wins the support of Emerson that eventually turns into a point of contention between the two, and spends time in Boston slaving over the presses when local publisher Thayer & Eldridge agree to publish his poems.

Elsewhere, “Rebel Souls” follows Artemus Ward across the U.S. and the Atlantic where he slays audiences with his comic lectures (Martin posits him as the world's’ first stand-up comedian). The author also takes us out west with Ludlow who hoped in vain to reverse his recent bad luck with a follow-up to his sensational book, “The Hasheesh Eater,” and puts us onstage as Menken does her “famous naked lady” act — on a live horse, no less. Most of these trailblazers were dead before 40. Clapp himself would make it to 60, but end broken and dissolute, an alcoholic who spent much of his later years in asylums. Vive la vie bohème, indeed.

Whitman’s years in Washington during the war, tending to the souls of the wounded, will endear the poet to readers all over again. He would live on and find growing fame after the war, surviving to pay a final visit to Pfaff’s in the summer of 1881, though by then the bar had changed location a couple of times and grown respectable. Martin writes how the proprietor, Charlie Pfaff, greeted the aged and sickly poet before retrieving a bottle of the establishment’s finest wine. “He poured a glass for Whitman and took a seat across from him. Then they talked about the old times, about that little vaulted room in the Broadway basement, and about the Bohemians… most dead, all gone. ‘Ah, the friends and names and frequenters,’ marveled Whitman, ‘those times, that place.’”

In “Rebel Souls,” Justin Martin renders those times, these bold Americans and the places they strode with telling detail. It’s a story about the risks and rewards of being an original and the far-reaching effects this can have.