Advertisement

MacArthur 'Genius' Money Lives On In A Poet's House

Resume

The winners of this year’s MacArthur Fellowships — the “genius grants” — have been announced, and the recipients include lawyer Mary Bonauto with the Boston-based group Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders and Harvard mathematician Jacob Lurie. All 21 winners will receive $625,000 over five years — no strings attached.

If you're like us, perhaps you've wondered what past MacArthur fellows have done with their money? Well, a 1992 winner’s MacArthur legacy continues to live on in western Massachusetts.

Poet Amy Clampitt was on a Maine vacation when she got the news via telephone from her dear friend, writer Karen Chase.

“And she was furious with me because she thought I was teasing her," Chase recalled. "And by the end of the conversation she said, 'I'm going to buy a house in Lenox!'”

Lenox, nestled in the Berkshires, was home to Edith Wharton, one of Clampitt’s favorite authors. Chase helped Clampitt find her cozy, quiet clapboard house a stone's throw away in nearby Stockbridge*. Chase showed me around recently.

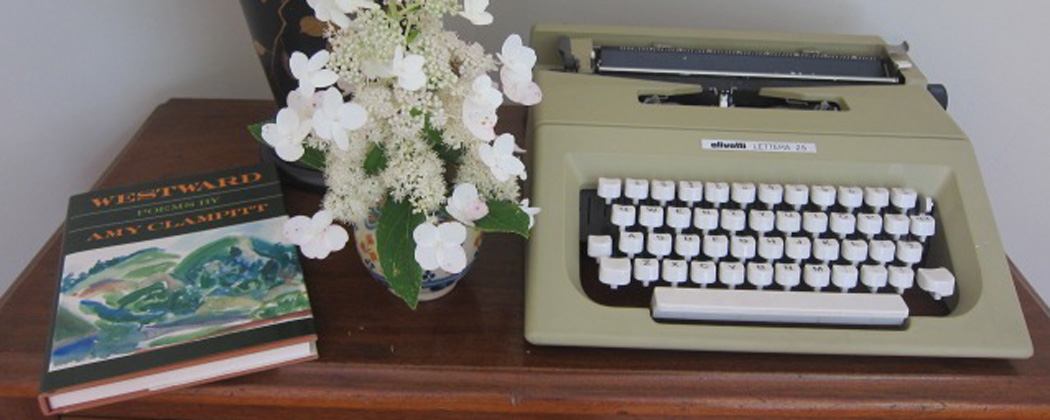

“This was her Olivetti typewriter,” Chase said, pointing it out in the room where Clampitt’s mother-in-law slept.

A tiny child’s writing desk is a focal point in the poet’s bedroom.

“We found this in a little antique store,” Chase recalled. “There was something very little girlish about Amy.”

The house was the 72-year-old poet’s first major purchase — and her first real home. Feeling uprooted and untethered were themes that fueled the Iowa-born writer’s work. Sadly Clampitt didn’t get to enjoy her new house for long. One year after getting the MacArthur award she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer.

Clampitt spent the last months of her life resting in the kitchen. Her bed was moved there so she could watch the birds in the backyard.

Chase remembers those days. She pulled out a folder of notes from a conversation Clampitt had with her husband Harold Korn eight days before she died in September 1994.

“What's going to happen to the house?" Clampitt asked. "I don't want it broken up.”

“It's ours…it's ours together…it always will be," Korn said. "I'll keep it that way the rest of my life.”

After his wife’s death, and before his own in 2001, the legal scholar dreamed up a fund — designed and administered by Berkshire Taconic Community Foundation -- to “benefit poetry and the literary arts.”

Since 2003 the house Clampitt bought with her MacArthur money has been home to working poets for six to 12-month, tuition-free residencies.

Chase is one of the four committee members who come together each September to choose the winners. Surprising as it may sound, she thinks Clampitt would be shocked to know this is happening.

“That 20 years after her death we're all in her house talking about this? She would die again if she could see us all," Chase said. "That's how shocked she would be.”

Clampitt herself didn’t see her first volume of poetry published until she was 63. Her career ignited after getting her work into the pages of The New Yorker. In a 1987 NPR interview, Clampitt recalled the life-changing moment.

“I suppose the first real publication that counts for anything — that amounts to anything and is regarded as breaking point — was in 1978,” Clampitt said. “I'd been sending things there for years and years, and they finally took one.”

Mary Jo Salter remembers that piece too. She wrote the forward to "The Collected Poems of Amy Clampitt" and is on the committee with Chase. In the '70s Salter worked for The Atlantic Monthly where she stumbled on Clampitt’s submission.

“When I was 24 years old I was the lowest form of editorial life at The Atlantic Monthly,” she recalled. “I had been reading the slush pile, as they call it, with work from the people who don't have agents or connections.”

But Salter recognized Clampitt’s name from The New Yorker poem. Not long after that she helped shepherd a manuscript to editors at the publishing house Alfred A. Knopf, including Ann Close.

“I was four or five poems in when I came across the 'Beach Glass' poem,” Close recalled, as she sat on the couch in Korn’s study. “And I thought, 'Oh, we have to publish this woman.'”

Close, who also helps select the residents, said Clampitt skipped around the block when she got the call about her first book deal. And Salter remembers how, almost in an instant, the 63-year-old poet’s life was turned upside down.

“I mean suddenly she is — in the poetry world — famous,” said Salter, who thinks Clampitt would be delighted that her house is something of a poet shelter. “This is the kind of thing that would’ve meant something to Amy if she herself had been given six months or a year not to worry about earning a living and just have a quiet place to write.”

One rising writer who’s benefitted from the Clampitt house is John Hennessy. He was a resident in the fall of 2007.

“You could feel Amy’s presence here all the time,” the poet remembered, smiling. “Sometimes in strange ways. You’d take a book off the shelf and a train ticket might fall out — it had been a bookmark. But more importantly you would find her notes to herself.

“You would leave your work and go into someone else’s — and get rejuvenated — and come back to your own,” he added.

Hennessey composed a healthy portion of his book “Coney Island Pilgrims” here in 2007. It finally came out last year.

Hennessey believes there can be misperceptions about what grant recipients actually do with their money.

“Well, you know, there’s this story of Anne Sexton getting a Bunting Fellowship at Radcliffe — they’re now called the Radcliffe Fellowships — and supposedly she put a pool in,” Hennessy said. “But I think that’s an exception right? Most of us live off grants that — if we get them — they go for food.”

The Clampitt Fund residency committee met this past weekend to choose the 2015 visiting poets. In December the 19th resident of the house Amy Clampitt purchased with her MacArthur purse will settle in and get to work in Stockbridge. And among the things that will likely inspire them is a small, glass box on the mantle that’s filled with Clampitt’s beach glass collection.

'BEACH GLASS'

While you walk the water’s edge,

turning over concepts

I can’t envision, the honking buoy

serves notice that at any time

the wind may change,

the reef-bell clatters

its treble monotone, deaf as Cassandra

to any note but warning. The ocean,

cumbered by no business more urgent

than keeping open old accounts

that never balanced,

goes on shuffling its millenniums

of quartz, granite, and basalt.

It behaves

toward the permutations of novelty--

driftwood and shipwreck, last night’s

beer cans, spilt oil, the coughed-up

residue of plastic--with random

impartiality, playing catch or tag

or touch-last like a terrier,

turning the same thing over and over,

over and over. For the ocean, nothing

is beneath consideration.

The houses

of so many mussels and periwinkles

have been abandoned here, it’s hopeless

to know which to salvage. Instead

I keep a lookout for beach glass--

amber of Budweiser, chrysoprase

of Almadén and Gallo, lapis

by way of (no getting around it,

I’m afraid) Phillips’

Milk of Magnesia, with now and then a rare

translucent turquoise or blurred amethyst

of no known origin.

The process

goes on forever: they came from sand,

they go back to gravel,

along with treasuries

of Murano, the buttressed

astonishments of Chartres,

which even now are readying

for being turned over and over as gravely

and gradually as an intellect

engaged in the hazardous

redefinition of structures

no one has yet looked at.

*Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly stated the location of Amy Clampitt's house. It's in Stockbridge, not Lenox.