Advertisement

What Would It Take For You To Kill A Demon, Real Or Imaginary?

Can you teach an old dog new tricks? Can a writer get out of his or her comfort zone — or more to the point, get out of his or her fans’ comfort zone — and try something a little different? That’s the question raised in new books by two of the best crime writers around, Ruth Rendell’s “The Girl Next Door” and Needham author Dave Zeltserman’s “The Boy Who Killed Demons.”

What “The Boy” and “The Girl” have in common is a willingness to play around with genre writing, not just do what they have won plaudits for, but to stretch their muscles, find different kinds of people to write about, explore new territories.

Zeltserman has long doubled as a mystery and horror writer, and he’s equally riveting at both. “The Boy Who Killed Demons” marks Zeltserman’s flirtation with young adult fiction. A high-school boy is at war with the world of adults. His touchy-feely parents, his suspicious teachers, anyone in authority, really. They just don’t understand kids, particularly kids who have the gift of second-sight, a shining, when it comes to seeing the demons who are out there, plotting to open the gates of hell. What’s a kid to do? Haley Joel Osment, the boy who saw dead people in “The Sixth Sense,” had it easy.

Or are these “demons” really just manifestations of his alienated paranoid mind, a fantasy video game come to life in which a hero has to take the world’s problems onto his young shoulders, a la his heroes Spider-Man and Batman (the Dark Knight version, of course)?

Zeltserman has an answer to that question, which I won’t disclose, but it’s a clearer one than in his excellent “The Caretaker of Lorne Field,” in which you wondered if the caretaker really needed to weed a field to keep monsters at bay or just needed to find the right medication.

We have similar issues with Henry Dudlow, who at 15 ½, notices that there’s something wrong with a guy in his neighborhood in Newton. The amiable face he presents to the world is a façade; Henry can see his real face — that of a ferocious demon. Buffy the vampire slayer at least had a guru and a posse to help her. Henry is on his own, armed only with the Internet and an ancient textbook. (He has to steal his friend’s father’s first-edition Spider-Man to pay for “L’Occulto Illuminato.”)

Zeltserman tries to see the world through the eyes of a coming-of-age Millennial and for the most part it results in some sly humor – “My mom [has] been losing the battle with middle age of late, and her Botox treatments and her near manic hysteria to work out each day in a futile attempt to keep herself toned and slender has left her looking mostly freakish and bony.”

Henry’s also a little too self-possessed, too sure of himself. Zeltserman wants him to make observations that I’m not sure he’s capable of. It’s a dilemma, because those observations are part of the book’s charm. It also takes the story too long to get into full gear. Henry’s research into killing demons can bog the first half of the book down in places.

But as he arms himself for the apocalypse, the book becomes the kind of page-turner that Zeltserman regularly produces. And Henry, himself, wonders about his own hold on sanity: “I have to admit, when I watched the video of me killing the demon Todd Robohoe as if he were only a frightened man, I felt a twinge of uneasiness when I wondered if I could’ve been hallucinating all that demon stuff after all.” And when Henry starts competing with an alleged demon for the love of a beautiful teenager we really begin to wonder if his murderous thoughts are really for the benefit of humanity or the latest version of teenage wasteland.

I’m hardly an expert on young-adult taste, but my guess is that younger readers will take to Zeltserman’s digs at his own generation, as well as to the story itself. Adult readers will be more skeptical, I think, and I wouldn’t say that this is the Zeltserman horror novel to start with — that would be “The Caretaker of Lorne Field.” But it’s a welcome addition to the writer’s prolific collection. I’d rather he get back to adults killing demons (literally and figuratively), but it was fun spending time in Henry’s company.

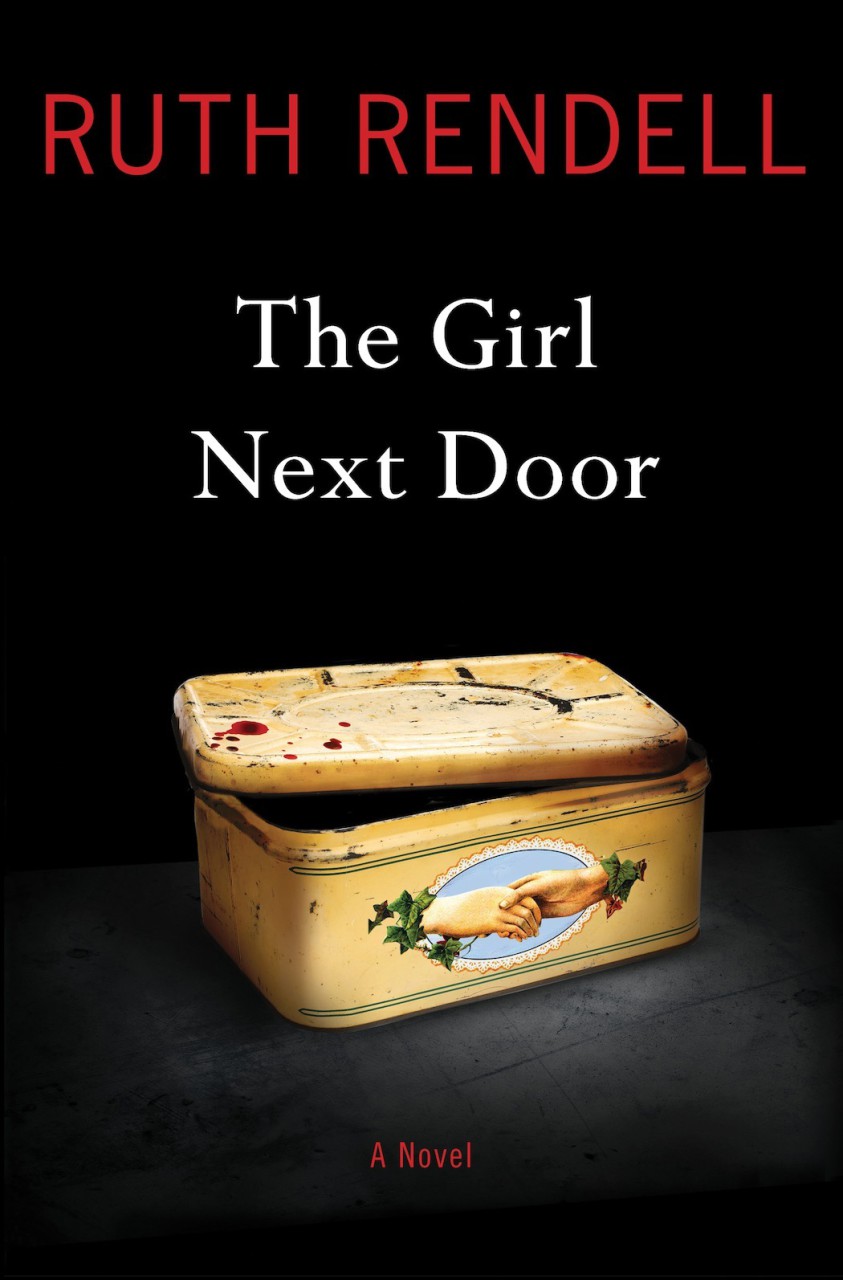

The Girl Next Door

Ruth Rendell (AKA Barbara Vine) is spending her time with folks at the opposite end of the spectrum. A group of British friends, now in their 70s, are jolted by the discovery of two skeletal hands in a biscuit box, one belonging to a woman and the other to a man. A flood of memories is brought back, not only to discover whodunit but to reminisce about roads not taken, relationships not developed.

Rendell has never shied away from the bedroom. While hardly erotica, Rendell’s novels are always alive to sexual possibilities — the Inspector Wexford novels less so. Now 84 herself, she’s not about to let the young folks have all the fun. Her later books aren’t as charged, or as dark, as her earlier ones, but they’re still must-reads.

There’s still that elegant writing and unsentimental limning of human behavior (the book begins with a description of one of her prototypical lethal working-class cads). The overlay of Gothic romanticism from her youth is more likely to be draped by crafty wit these days. (Hear an excerpt.)

She is known as the queen of psychological thrillers and while the thrills aren’t paramount in this book, the psychology is as sharp as ever:

“It is a fantasy many have, a kind of dream, a place to think of to send one to sleep. It begins with a door in a wall. The door opens, confidently pushed open because what is on the other side is known to the dreamers. They have been there before. They have seen somewhere like it, somewhere real, but less beautiful, less green, with less glistening water, fewer varied leaves, and where the magic was missing … The dreamers never leave the secret garden. The garden leaves the dreamers.”

Alan Norris is one of those characters deserted by the garden, but the discovery of those hands brings back the dreams of his youth, particularly of Daphne Jones, the sexy woman with whom he was once entwined. Now he’s settled for a decent, unadventurous life, at least until all his friends have been reunited by the police to see what they can find out about those hands.

As he starts thinking about taking a last chance to make those dreams at long last a reality with Daphne, we wonder which of these characters might be capable of murder. Not as in one of those cozy good-and-evil British mysteries, but as in what any of us might be capable of, given the wrong circumstances.

Rendell’s characters in this book are lovable not because they’re Agatha Christie cute, but because they’re so well drawn, so believably sad as they face the final years, so easy (in some cases) to cheer for in their last stabs at love.

Not your typical crime story then. But it is a typical Rendell book — cunningly observed, elegantly written. As you read “The Girl Next Door,” it’s hard not to root for them to find something meaningful in the end. And for there to be no end to Ruth Rendell novels.

More: