Advertisement

It's Great To Say It, But Are We Really Charlie Hebdo?

How do artists respond to political terror? In dictatorships, often with their lives. Even Shakespeare had to do a delicate balancing act to keep his Elizabethan head on his shoulders. It seemed fundamentally different, though, when editor Stephane Charbonnier and the cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo paid for their satire with their lives.

They weren’t living in a dictatorship, but in a democracy. The killers weren’t kings but terrorists. And instead of art trying to bring solace and understanding to the public, the public brought solace and understanding to the artists in the form of holding up pens at vigils and declaring “Je suis Charlie.” The reaction even brought applause from Salman Rushdie, who knows a thing or two about threats to free speech.

The global reaction is laudable, but there's the nagging feeling that many — most? — of us are really not so Charlie when it comes to threats against freedom of speech. It would be idiotic to compare censors among us with the French terrorists, but it’s easier to say “Je suis Charlie” than to practice it.

Look how quickly, for example, American theater chains pulled the plug on “The Interview” and how Sony had to be shamed by President Obama and others into not kowtowing to the threat of terrorism.

And that’s just the tip of the political iceberg. Comedy Central censored “South Park” — one of the closest entities we have to Charlie Hebdo — bleeping out references and deleting images of Muhammad in one of its episodes in 2010.

In 2006, Deutsche Oper in Berlin canceled Mozart's “Idomeneo” because of a scene depicting the severed head of Muhammad — along with those of Jesus, the Buddha and Neptune. German chancellor Angela Merkel complained about self-censorship, and the show eventually went on.

The New York Post reported in 2010 that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had pulled three paintings showing Muhammad. The Met then did bring the paintings out a year later, according to the Post.

Abraham Foxman and the Anti-Defamation League bullied New York’s Metropolitan Opera into canceling the global simulcast of John Adams’ “The Death of Klinghoffer,” which looked at the Achille Lauro barbarism from all sides, including that of the Palestinian terrorists. Although Foxman admitted that the opera wasn’t anti-Semitic, he argued that it would encourage anti-Semitism around the world.

And Foxman was considered a sellout by some Jewish demonstrators for not pushing the Met to cancel the opera altogether on the basis that it’s too sympathetic to Palestinian terrorism.

Then there’s the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s response to censorship. With music director Seiji Ozawa’s blessing, the BSO fired Vanessa Redgrave as narrator of “Oedipus Rex” in 1984 because of her activism on behalf of Palestinians. And in 2001 the BSO canceled a performance of selections from “The Death of Klinghoffer” after the Sept. 11 terrorist attack in New York.

The BSO cited a fear of disruption from the Jewish Defense League in the Redgrave case and sensitivity to a member of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus who lost a family member in the attack when it canceled Adams. Robert Spano, who was set to conduct the Adams piece, said, “It seems inappropriate to perform excerpts from an opera about a terrorist act right now.” Adams countered in an email to The Boston Globe that he disagreed “not only because it presumes the BSO’s audiences only want comfort and familiarity during these difficult times, but also because it sets a precedent that there is poetry and music that should not be performed at a given moment because of its content.”

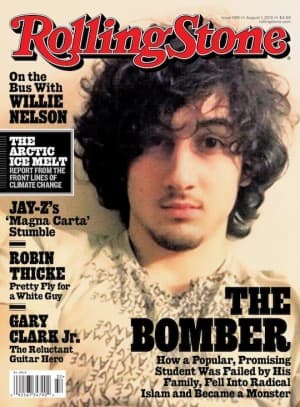

In 2013, stores removed copies of Rolling Stone because the cover was deemed too sympathetic to alleged Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev even though the headline called him "a monster."

Of course you could argue that what happened in France shows that perhaps discretion is the better part of valor. Is “The Interview,” by most accounts a terrible comedy, worth the possible loss of life in a multiplex bombing? Is Adams’ music worth the threat of a bomb at Symphony Hall?

If you’re going to say “Je suis Charlie” then the answer has to be an unequivocal “yes.” Let’s hope that Andris Nelsons’ middle name is Charlie; there haven’t been many Charlies in the BSO’s past.

The Adams opera is instructive in another way. As the 24-hour news cycle makes political events look like episodes of “24” it behooves the arts to present an alternative to culture warriors and ideologues who want to silence the other side. No one in his right mind would equate those who wanted to silence Charlie Hebdo with bullets and those who wanted to silence John Adams with nonviolent threats.

But art needs to go beyond the headlines and beyond liberal or conservative orthodoxy. Zayd Dohrn’s “Muckrakers” does that at the New Repertory Theatre in terms of dramatizing whether transparency is as good a thing as Edward Snowden’s supporters say it is. (I saw it at Barrington Stage in Pittsfield, Mass.) The New Rep also had an insightful play about the drone strike bombers and those being bombed in local playwright Walt McGough’s “Pattern of Life” last year.

The debate in Europe is far more intense than here. Jews who are the victims of new anti-Semitic horrors and Muslims who are the victims of economic racism provide a backdrop that’s artistically as well as politically volatile. In fact, the last issue of Charlie Hebdo before the bombing took to task author Michel Houellebecq for his novel, “Submission,” which imagines a futuristic France with a Muslim president, and Islamic law replacing the secular society. The novel was released Wednesday and was No. 1 seller on Amazon the day before the assassinations at Charlie Hebdo.

Islamaphobia? Maybe. But don’t we want our artists to go outside the orthodoxies of the left and right, to drop their censor and make us think about issues in a different way?

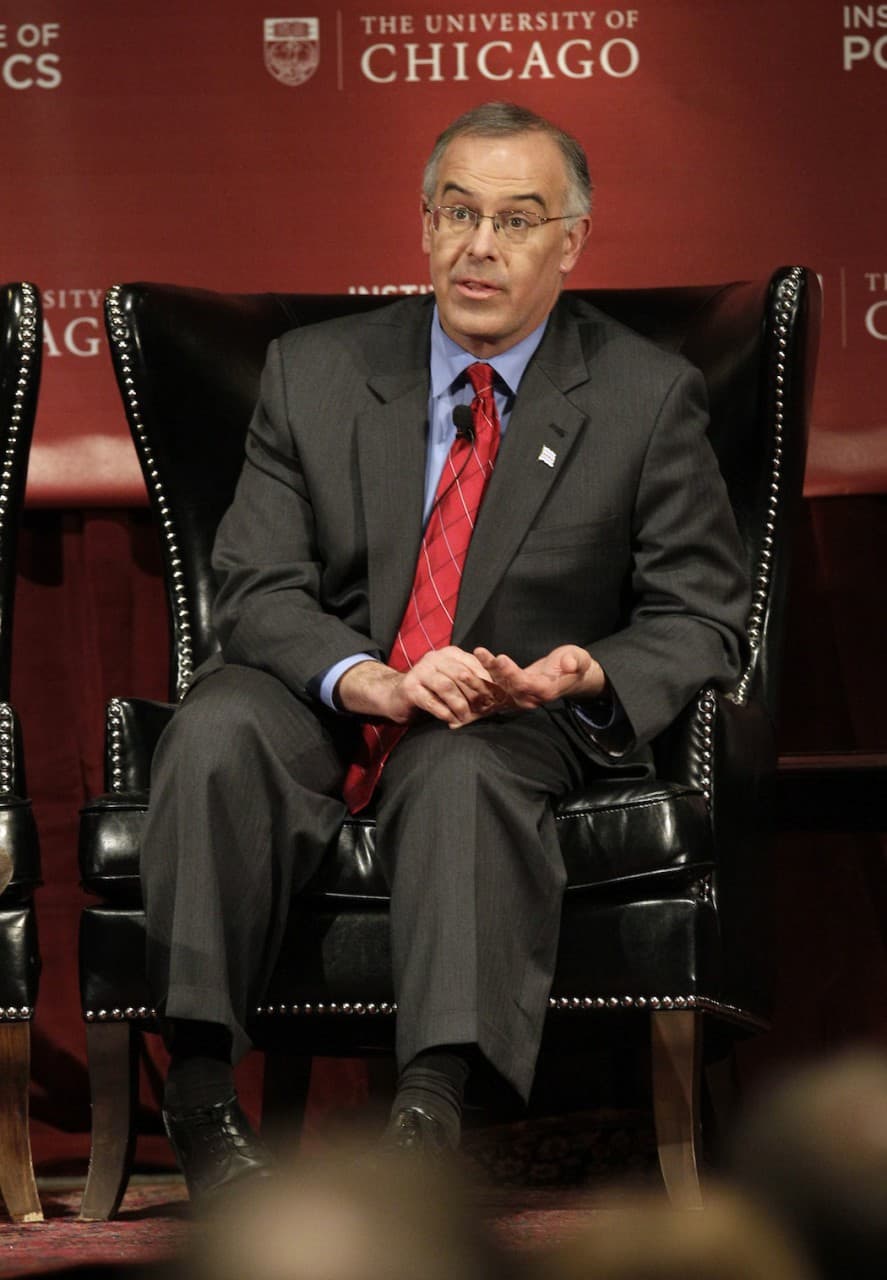

Of course, Charlie Hebdo didn’t call for the censorship of “Submission,’’ but the debate in this country about what can and cannot be said often takes on censorious overtones. New York Times columnist David Brooks noted on Friday:

“The journalists at Charlie Hebdo are now rightly being celebrated as martyrs on behalf of freedom of expression, but let’s face it: If they had tried to publish their satirical newspaper on any American university campus over the last two decades it wouldn’t have lasted 30 seconds. Student and faculty groups would have accused them of hate speech. The administration would have cut financing and shut them down.”

There are calls for academic and cultural boycotts of Israel on one side and Hollywood threats to blacklist Penelope Cruz and Javier Bardem for calling Israel’s Gaza bombings genocide on the other.

So let’s applaud Sunday’s unity mobilization and, yes, let’s all say “Je suis Charlie.” But let’s mean it this time.

Ed Siegel is critic at large and editor of The ARTery.