Advertisement

How’s It Feel To Fill Big Shoes In Devo And New Order? Two Bostonians Find Out

Devo hailed from Akron, Ohio, carving out territory on the acerbic, art-rock end of the new wave spectrum during the late-1970s. New Order rose up out of the ashes of key post-punk band Joy Division in 1980. They hailed from Manchester, England, and brought a certain elegiac grace and sadness to electronic music in the early 1980s.

Both bands became major acts during the ‘80s and have continued on—with various interruptions and iterations—into the 21st century. And both of these iconic bands now boast key members who call suburbs west of Boston their hometowns.

Devo’s Josh Hager, 44, was raised on Long Island and moved to the Boston area in the early ‘80s. For much of the ‘90s, he led the controversial ‘90s Boston band, the Elevator Drops, and later played with the Weezer offshoot, The Rentals. Hager replaced Devo guitarist-keyboardist Bob Casale (aka Bob 2), who died last February at 61, due to heart failure.

Tom Chapman, 42, was born in France, but moved to Manchester, England, at 20, primarily because he loved its music, bands from Joy Division to the Fall and the Smiths. He joined New Order guitarist Bernard Sumner’s side group Bad Lieutenant in 2009 and then, when New Order reformed in 2011, took the place of founding bassist Peter Hook, who’d acrimoniously exited the group in 2007. (Hook’s version of the events.) Chapman, who plays guitar and keyboards, is also part of the Manchester duo Rubberbear with ex-Fall bassist Steve Trafford.

Chapman relocated to the Boston area almost two years ago after his wife, who’s in finance, landed a job here. Chapman figured all he had to do was be near an airport in able to get where the work took him. “It’s fine and I’m enjoying being in Boston,” he says.

New Order is about 75 percent done a new album, Chapman says, with a hoped-for autumn 2015 release and a concurrent tour—“back on the hamster wheel,” says Chapman—taking them into next year.

“The last two albums were quite guitar-ish,” Chapman says, “so we made a conscious choice to work towards a more electronic-based album. We’ve already previewed two tracks last summer in the live show, ‘Plastic’ and ‘Singularity.’ They’ve gone down really well.”

Hager and Chapman live about 15 minutes from each other and were introduced by reality TV show producer Lance Nichols. The became friends—and collaborators. Recently, they laid down tracks in Los Angeles for a new band, Stars of Suburbia, with Devo drummer Jeff Friedl and the other New Order newbie, guitarist Phil Cunningham.

“It’s cool, a really good cross between dark Manchester-y stuff and Liverpool-y Echo and the Bunnymen stuff,” says Hager. “And also this ‘Scary Monsters’-era Bowie with a bit of T.Rex ‘Electric Warrior.’”

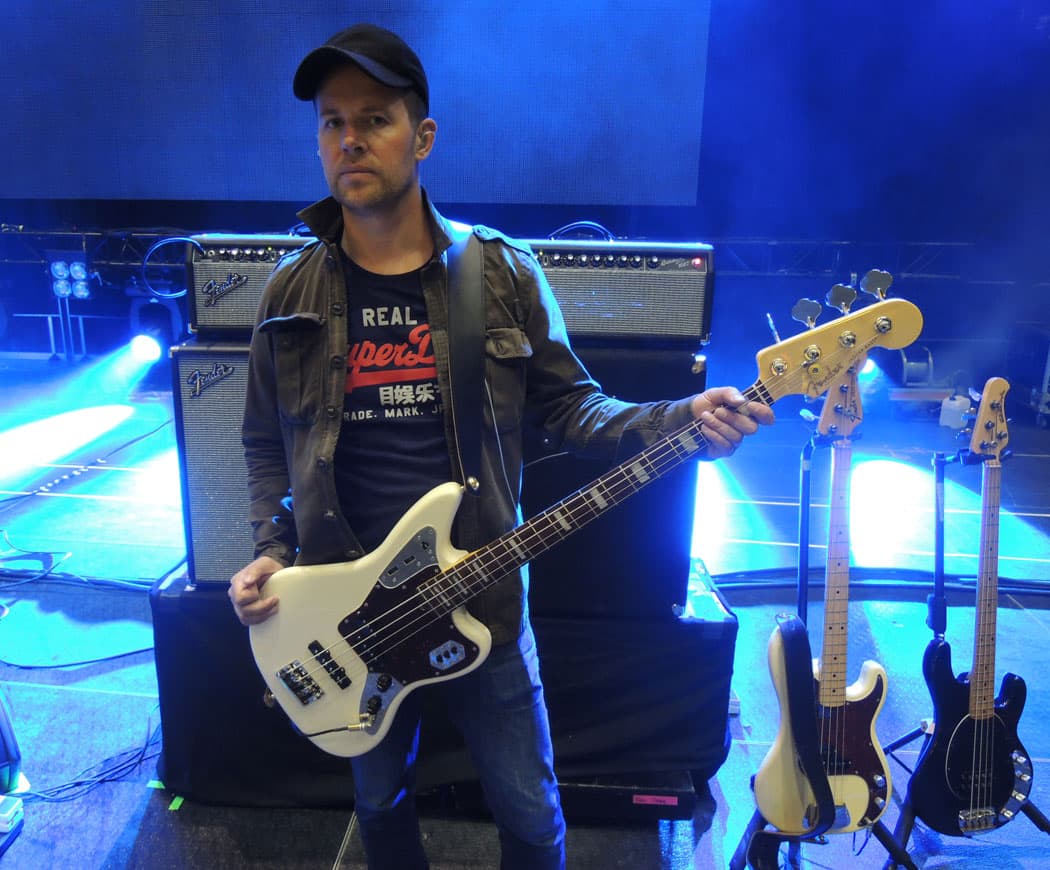

Tom Chapman

You came to New Order through Bad Lieutenant.

Chapman: Bad Lieutenant needed a bass player because Alex James, who plays in Blur was initially part of it, but was based down south [of England] and couldn’t really commute with the rest of the band which was based in Manchester. They knew they were going to need a bass player to fill in for the live show. I came in for an audition and you can imagine there was a bit of trepidation on my part when I walked in the rehearsal room and it was [New Order’s] Stephen [Morris] and Bernard over there and they say, “Right, let’s do “Transmission,” “Blue Monday.” It went really well. I think I played well and I got the job. We toured about two years.

The transition into New Order happened how?

A friend of New Order’s, Michael Shamberg [New Order video producer/founder of the US division of Factory Records]. It was 2011 and he was quite ill—he recently passed away—and he asked Bernard if he would reunite New Order for some charity concerts to pay for his care. Having done so much for the band, it was a no brainer for them. They said yes right away and that was really the reason New Order got back together. 2011, and we talked about it in June and our first show was in October.

Was there any attempt to get Hooky back in this?

No, it was me. There was no attempt to get the ex-bass player back. He wasn’t asked to join the group in 2011 because he left the band in 2007. I must honestly say that there was no alternative plan to carry on as New Order. We were going to do those two shows for Michael and see what happens but there wasn’t a master plan. First thing, when we sat down was “We’ll do those two shows and see what the reaction is like” with me being on bass duty and we took it from there. And luckily those shows went down a storm. I think our manager started getting offers round the world to play as New Order and that was the start of this three-year world tour that we did. We didn’t know what was going to happen.

You mentioned trepidation auditioning with Stephen and Bernard. Was there any trepidation about stepping into Hooky’s role?

I am confident with my abilities as a bass player so I knew it wasn’t going to be a problem to play the part. We used to play New Order songs in Bad Lieutenant as well. However, there was a bit of nerve-wracking, the first night in Belgium, our first gig. I didn’t know what was going to happen, what the reaction from the fans was going to be, but it went down really well and the band sounded great. So that geared me up to say, “I can do this, let’s do it.” It took me a while to realize I was playing in New Order.

What is like working with Bernard? Is he the boss as well as a bandmate?

I wouldn’t say he’s the boss, but I’d say he’s the captain in a lot of ways. He’s the one who sits behind the computer a lot and there’s only one person who can do that. On this new album that we’re working on everybody has contributed musically. We’ve all brought it ideas to work with as a group.

You’re a generation under Bernard and the others. Is there any conflict or clash because of that?

No, it’s funny with them. There’s just that whole thing that playing in a group keeps your mind quite young and fresh. So there’s not been any sort of age difference. It’s not been a problem at all.

Did you need to take a Joy Division/New Order history lesson?

I knew quite a lot because growing up I had a really keen interest in the Manchester music. They’re one of these bands that have an incredible legacy. They were a band that really thought outside the box and wanted to do things differently and with a lot of musical integrity. They weren’t as much after a paycheck as they were creating more good music.

The transition from Joy Division to New Order came about, obviously, because the singer Ian Curtis hanged himself, but the move to a more electronic sound was, at the time, kind of radical. Maybe it seems less so now, over time.

I’ve had this conversation with Bernard, him telling me how they became interested in electronic music, him telling me that he was inside a club in New York one night and looking at people dancing and thinking, “It would be great if people did that to our music.” Stephen and Bernard became interested in new technology; they were drawn to synthesizers and drum machines and wanted to experiment with them, and that made them pioneers with electronic music, obviously also having a rock side to them. It was a perfect hybrid band.

Josh Hager

I wrote about your band the Elevator Drops in 1996 and called you “nasty little pop flies in the rock ointment, styling themselves as a sarcastic antidote to serious grunge." How do you look back on the band?

Hager: Oh my god, it was like a Dadaist mashup of all of your favorite bits of rock ‘n’ roll history. What we were trying to do was take the best elements—a little bit of Led Zeppelin, a little bit of Devo, The Police and Gary Numan and Kraftwerk—condense it and try and put it to a show on a scale of Kiss or Kabuki.

While confusing and pissing people off.

It was a big social experiment. Most of the misunderstanding of the Elevator Drops I think was just the fact that we had an odd sense of humor. We thought everything was hilarious. The E. Drops was like 1993 to 1999. I was Garvey J. It was a character name for a multiple personality disorder I guess. The thing with that incarnation of Garvey J that was really strange that people still don’t believe is I don’t remember much of the Elevator Drops shows, because it was an actual transformation. If I started putting that makeup on by the time I was done I was in such a state that I became another character, like full immersion.

And as a member of Devo you’re sort of playing a character too.

Yeah, you get to a certain point in your life where “Is it a character or is it just you, one of the facets?” The thing with Devo is it’s in my DNA. I’ve been loving that band for so long that it felt completely natural. I had known the guys going back to 2009. My brother Paul was recording with [Devo keyboardist] Jerry [Casale]. I happened to be in California and Jerry needed someone to record on a friend’s project. Paul called me up and we booked some time.

After Bob 2 died a year ago, what did they do?

What happened was they went off and did the “Hardcore Devo” tour [playing material recorded 1974 to 1977] last summer and gave a lot of the money to Bob’s wife. After that they had some dates that were on the books for the greatest hits set, which was a lot more involved and my brother brought it up to Jerry. I had mentioned it to Jerry before saying “If you ever need a hand with anything, I’m your guy.” They must have called me on pretty short notice before the first shows with Arcade Fire [last summer], a month before maybe.

There must have been some learning curve, getting comfortable, or did you drop in, put on the big, baggy yellow suit and say, “Hey, I belong here”?

The only part that was uncomfortable [about joining them] is that Bob 2 is so loved and so missed that that just feels kind of bad. We were about to go on in Times Square in October and Bob 1’s [guitarist Bob Mothersbaugh] sitting there and it’s kind of quiet and he looks at me and says, “I hope you’re not offended, but I really miss Bob right now.” I was like, “Of course, I’m not offended.” At the same time, I feel like I’m trying to keep his name alive in a lot of ways, keep his legacy going.

You had a bit of a mishap at that gig in front of 40,000 people, right?

Yeah. I’d never broken a bone before so it was a completely alien experience. Very Devo. Third song in, “Uncontrollable Urge,” which has that big build-up and I just jumped in the air and parted my legs and you land. And the left leg just completely gave out like it was Jell-O. I hit the ground, popped back up and tried to step back down on the leg and the knee was just floating around in there and the leg didn’t function. I knew I was in trouble. Something was broken. Fractured kneecap.

But the guys in Devo didn’t know?

No, just the guitar tech. He came over and tried to give me a stool and I sat down for a split second and looked out at the audience and said, “I can’t sit down.” I got back up and played the whole set on one leg and made it look kind of normal. We finished the set and I came down the ramp and they put me on a stretcher. The band comes down and is looking at me like, “What’re you doing? What’s going on?” and I said, “I think I broke my leg.” I’m in the hospital and [singer-bandleader] Mark [Mothersbaugh] is texting me saying, “My god, I thought you were just trying to one-up us, really doing your research and doing one of those Bob 2 moves from back in the day where he used to lay on his side and kind of spin around on the floor.”

Did it knock you out of action for a while?

No, fortunately we didn’t have any shows until the Chile shows a month later. It gave me a while to heal and it worked out great.

Are you 100 percent now?

I’d say 90 percent. Probably be a few more months.

Are there plans for a tour?

I don’t know. There’s some things on the table for the summer. It depends on Mark because he is unbelievably busy.

What relevance do you think Devo has in the 21st century?

I always think Devo was so far ahead of their time it’s still relevant. The message, the concept, the ballsiness of what they do and the effect. And here’s these guys at their age kicking the shit out of other bands—professional, tight, doing what they do. They’re just an amazing band, conceptually and musically.

And they always had a cool, ironic take on merchandising—selling scads of Devo stuff, but taking the piss out of themselves and the fans, too. An early goof on rock consumerism.

Exactly. They’re very shrewd, but I don’t think they mean it with malice. There is a concept behind the whole thing. The radiation suits and the domes. It’s funny when people talk about the ‘80s and a Devo hat will pop up, just a single icon for a decade.

Correction: An earlier version of this post incorrectly identified the Devo drummer in Stars of Suburbia.