Advertisement

Full Speed Ahead: Prolific Choreographer Twyla Tharp Not Slowing Down Soon

“50 years ago was my first concert. Not many people have worked 50 years, and I have consistently.”

Choreographer Twyla Tharp studied with Martha Graham (“she was impeccable, regal, and you worked your best for her”), and Merce Cunningham, and danced with Paul Taylor’s company before setting out on her own at 23, founding Twyla Tharp Dance.

Now 73 years old, this famously-scary-to-interview genius is aggravated by the very notion of slowing down to smell the roses. “That’s foolish. That’s not my life. That’s not what it’s about. The roses are speed for me. The roses are not slow. The roses open fast. I’m not known for patience. But that’s okay.”

Having traveled on an early train from her home in New York City, Tharp was in Cambridge to participate in the Creativity Forum at Lesley University. In her room at the Charles Hotel, wearing a big grey sweater, black pants and white socks, Tharp fussed about what she’d wear to her Lesley Forum evening lecture at Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School auditorium. “I brought nothing warm, and it’s, yut, it’s cold here!”

I wondered how familiar Tharp is to people born after the dance boom of the '70s and '80s, this veteran dance-maker who started out 50 years ago by bravely breaking through walls to merge the vocabularies of ballet and modern dance. After she’d given her lecture and was taking questions from the audience it was obvious that students at Lesley were in awe of Tharp’s accomplishments. How could you not be? Tharp has created more than 129 dances, and choreographed a dozen TV specials, six Hollywood films (including “Hair,” “Amadeus” and “Ragtime”), and four Broadway shows, including the 1985 staging of “Singin’ in the Rain,” and, more recently, shows based on music by Billy Joel, by Bob Dylan and by Frank Sinatra. She’s created full-length ballets for the world’s major companies, and set figure skating routines for Olympians.

What’s left to do? Tharp answers, sometimes referring to herself in the third person:

“Look at me: I’m doing everything as fast as I can. We’re working on the archives. We are working on education programs. I’m teaching. I’m writing a fourth book. We have this tour going on in the fall. Just done a third new piece in one year. Ballets go out [to dance companies worldwide] and rep goes out. I look at video of the last rehearsals, give notes, and make that kind of connection with companies performing my dances.”

“The reality for me has always been to work as long and as fast as I possibly could, to learn as much as I possibly could. Now what do you do? You in a way have earned a beginning, where do you go? I’ve got to get through the fall, I’ve got to finish this book, and then we’ll see. I’m still making dances, I’m still evolving dance. That’s the basic mandate.”

Tharp’s three new dances comprise the program for a national tour that’s still in the planning stage. “We’re doing a 10-week tour this fall, with 12 dancers that’ve worked with me over the years, especially the ones who’ve been in the Broadway shows. We’re going to do 20 different stops anyway, which is a humongous undertaking, a really difficult tour. We finish at the Koch in November [David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center] and before that we’re in Dallas in September, Los Angeles, Toronto, in the Midwest. All new work: Bach and jazz.”

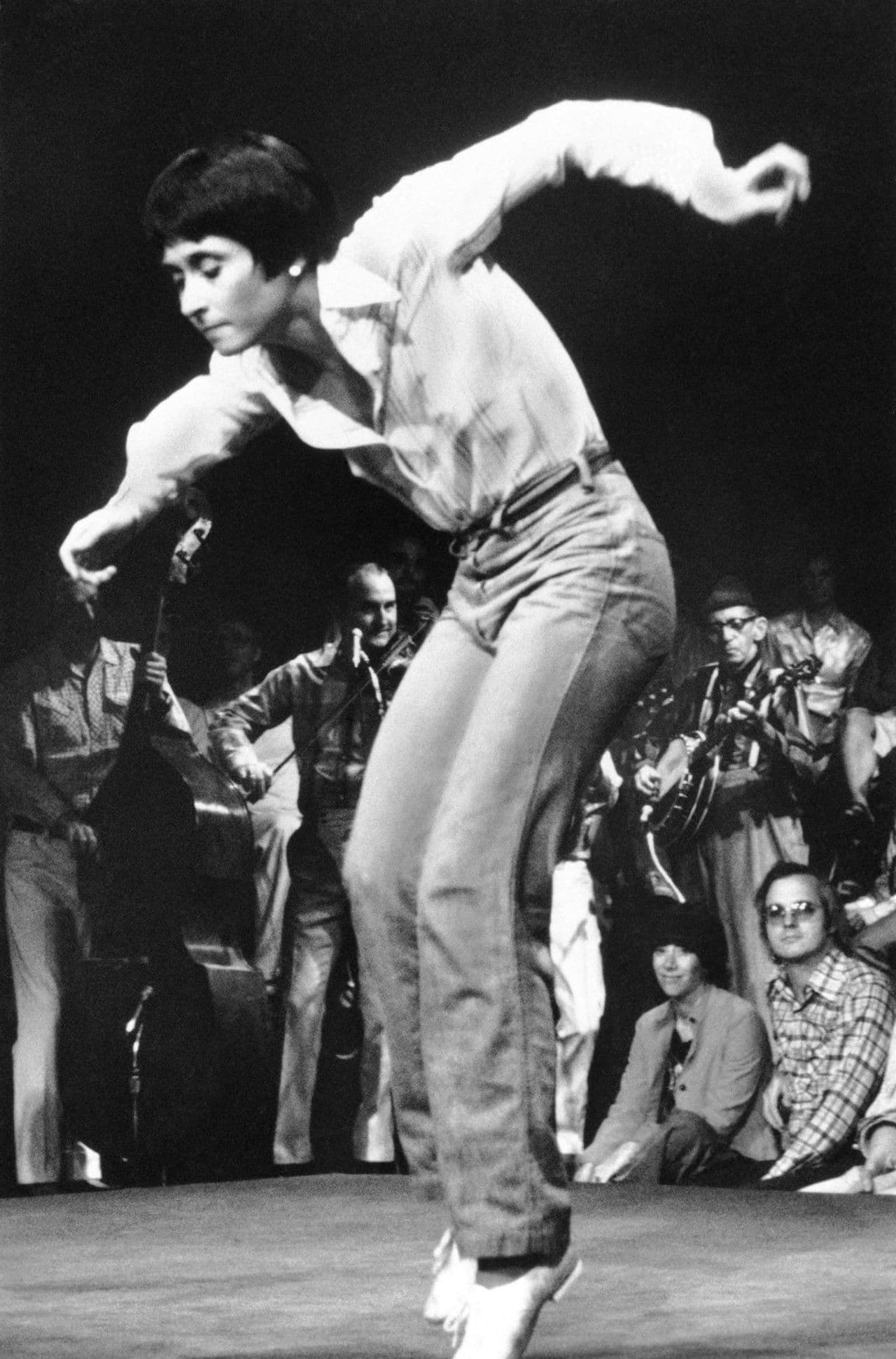

Tharp is proud of the fact that she herself danced professionally until she was 52. She’s an inch over five feet tall, but powerful and quick, a witty, charismatic performer. In a New York Times profile in 2006, Tharp spoke in the third person, atypically wistful about what she can no longer do: “You can see we miss dancing, you can see we like dancing, you can see we were a brave dancer.”

Tharp continues to be brave, looking straight out at the future, at a time when she won’t be around to represent her remarkable body of work. Her current focus is the creation of a complete archive of her work. “Do you know about TwylaTharp.org?” she asks, raising her eyebrows and tapping her big round eyeglasses into place. “No? Gah!” She dives for her iPhone and starts punching at the keys.

“This is something that we worked on over the course of the last couple of years in order to have a reference that would give people an overview of the work.” Tharp continues to punch at her phone, annoyed that the site isn’t coming up fast enough.

“Dance is the one art form without an artifact. It’s one of the reasons that dance is at the back end of the line when it comes to arts, because it doesn’t leave a monument for people to engage with and study and to see the history and tradition. Well, that’s changed because of technology. I’ve been thinking about archives for a long time, and about how people can access them.”

Tharp’s iPhone begins to cooperate, and her website pops up. “Aha! Here it is, see? It’s little on the phone, but you get the idea. For every single work there’s a container that has program information, music, videos, has a very brief comment for every piece and every item. That’s for the entire repertory, over 180 references and it goes by year, not by alphabet. I paid for it myself and I did it myself. I find often that’s the way to get work done.”

Tharp’s mother set her course as a thoroughly-schooled creative worker. “She was the classic tiger mom. She also was the breadwinner, an accountant, a geologist, a phenomenon in terms of her outreach and her insistence that it could be done.”

Her mother named her after Twila Thornburg, the "Pig Princess" of the 89th Annual Muncie Fair in Indiana. Thinking that Twyla with a “y” might look better on marquee lights, her prescient mother changed the spelling. “I had an extraordinary education,” Tharp said, recounting childhood lessons in German and French, several musical instruments (piano, drum, viola, violin), many dance disciplines (ballet, tap, jazz and modern) and stenography.

“The breadth of trainings I had was kind of amazing,” Tharp said. “And so I was able to bring all of that to bear when I was a freshman in college [she attended Pomona College, and transferred to Barnard College] and be able to look around and say what interested me. And the degree I knew I had to get because my mother expected it, that has been useful, particularly having a degree in art history is a very serviceable thing in my profession.”

Having a “serviceable” background may seem an odd goal for a creative intellect, but Tharp is unusually grounded and rational in the way she’s spent her career. “We all know that women have a high hill to climb whatever they do,” she said, “And the world of arts is very chauvinistic. One knows that going in. You’ve got to be able to pick up the tools and start building whatever you’re doing.”

Tharp has always counseled her dancers and students to consciously plan their careers, and she’s written extensively about knowing your audience, and creating work that connects with people.

“I don’t see it as pandering to the public when the work I do becomes slightly commercial in a sense, and succeeds. I always assumed that if one did quality work one would be like any other worker in our culture: able to support oneself, taking the responsibility of not being in an ivory tower.”

“I’m still scrambling to find a direction to keep moving in but I also have this repository of information that I think is important to share with young people. Which is why I wrote 'The Creative Habit,' the book I lecture on. It was written basically for college kids and I’m very pleased that it remains on the shelves and is used in courses. Its lesson is a very simple one, but it’s not so simple. It’s a kind of basic aesthetic, which is: you’re not going to get very far if you don’t know about tradition, so don’t try to take shortcuts. And don’t be intimidated by the past. And don’t think it’s going to staunch your creativity. That is ridiculous.”

In some ways, Tharp lives the same way she always has, staying in extravagantly good shape. “I can do 75 push-ups a day, and I can dead-weight two-hundred-and-some-odd pounds. I go into the gym only two days a week because I had a broken metatarsal. But over the course of a week I still lift a ton.”

However, some things change without Tharp’s permission: “Many of my friends have passed away. Generations are lost, so one becomes more solitary. You can make new friends, this is absolutely true, but friends are very different when they’re not from the same generation.”

What does Tharp see in the future? “I go on. To be honest I really, basically work. That’s what I do.”

Sharon Basco is a journalist, critic and public radio producer.