Advertisement

Never Heard Of 'Hero Of American Art' Thomas Hart Benton? You're Not Alone

Resume

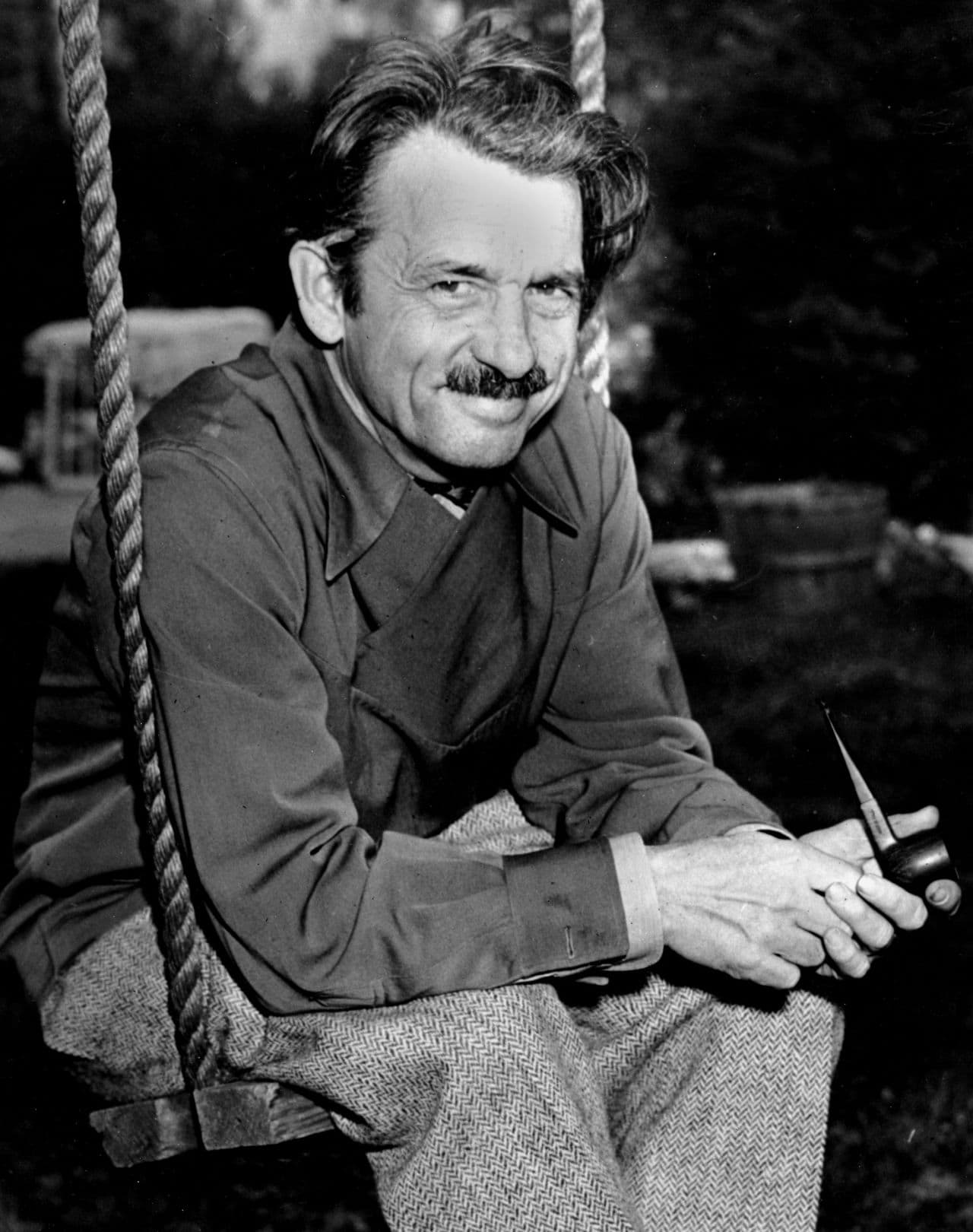

Maybe you've never never heard of 20th century artist Thomas Hart Benton, but there was a time when the Missouri-born muralist was something of a rock star.

"Thomas Hart Benton has been described as America's best-known contemporary painter,” broadcast journalist Edward. R. Murrow said back in 1959, as he interviewed Benton to mark the artist's 70th birthday.

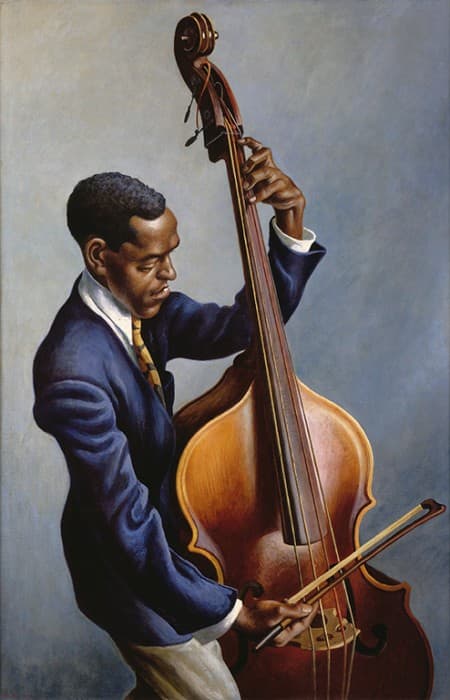

Benton's self-imposed mission was to paint "American histories," as he called them. He did that from the early 1900s until he died in 1975, always pioneering to make ordinary characters and stories into epic, colorful, often controversial works.

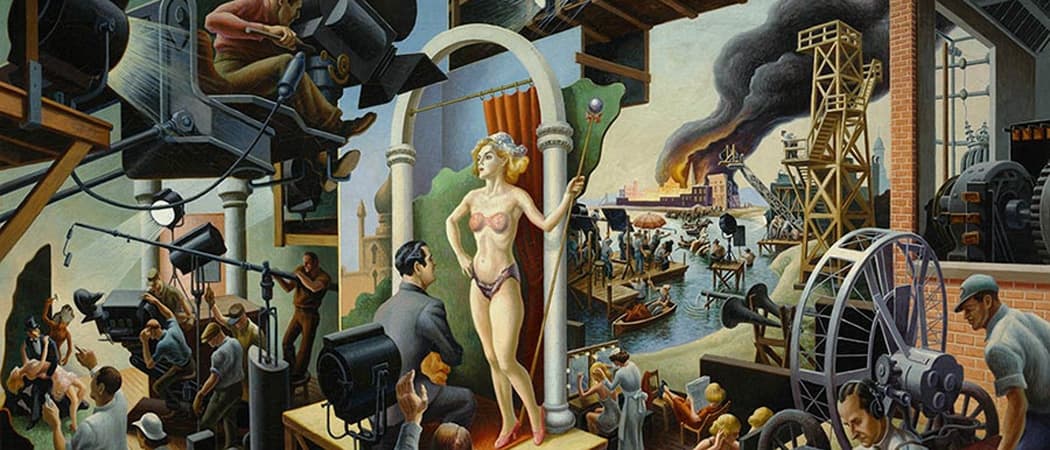

A new exhibition at Salem's Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), titled "American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood," shines a spotlight on the influential painter and his longtime, little-known relationship to Hollywood.

Benton Influenced By The 'Most Modern Form Of Storytelling'

In the 1930s, Benton won commissions to paint murals for places like the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and Missouri's State House. His face graced the cover of Time Magazine, which deemed him a “hero of American art.” But flash forward to now and Peabody curator Austen Barron Bailly says there hasn’t been a major exhibition about Benton in more than 25 years.

“His claims to fame these days, if people even know about him, is as a muralist and as a public artist,” she said.

Some know Benton was also a mentor to abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock. But even with that cred, Barron Bailly says curators from the four museums collaborating on this new exhibition made a pretty depressing discovery.

“When we were putting together the show we did an informal survey of museum-goers at all the participating institutions,” she recalled, “and we learned that only about one in four people coming through the door had ever heard of Benton.”

That’s a loss, Barron Bailey says, because Benton had a major influence not just in the art world, but ultimately on Hollywood and popular culture.

Early in his career — when motion pictures were new — he became obsessed with the narrative, emotional power he found in the cinema. Eventually Hollywood fell for Benton's style too. His on-going symbiotic relationship to the film industry is the focus of the new exhibition.

“Benton didn’t actually work on movies,” Barron Bailly explains, “with the exception of when he worked in the silent film industry — where he was painting backdrops and sets, and doing research for the scenery, playing a few bit parts, assisting directors.”

Benton’s engagement with Hollywood, she continues, was much more conceptual.

“He’s always aware of the dominance of Hollywood in American culture as the primary, most modern form of storytelling,” she said, “and then he does get the commissions to promote the movies. So those are some of the key connections.”

The curator says Benton’s Hollywood connections are often overlooked — or forgotten — even in art history classes. But his fascination with the drama and power in motion pictures played a major role in shaping his visual voice.

To make that point, in this exhibition the curators pair Benton's paintings with film clips. His earliest mural series, titled "American Historical Epic," is compared and contrasted to silent movies, including "The Last of the Mohicans." The artist's 14 large canvases hang in a row, like cells in a film reel. They depict violent scenes of Native Americans battling white settlers, puritans preparing to execute a witch, a slave being whipped.

“The year he conceives this [1919] is known as The Red Summer,” Barron Bailly explained. “There are race riots all over America, it’s the start of the Great Migration. So Benton is very tapped into the very urgent issues of his day, and in thinking about, how can we think about the past in relation to the present?”

'I Feel My Paintings In My Hands'

Benton constantly traveled. He roved the country searching for authentic stories, scenes and characters to populate his works. He found them in factories, rail yards and cotton fields.

In 1937 the artist got a life-changing assignment from Life Magazine. The editors sent him to Hollywood to create images of the movie industry for publication. But being Benton, he was more attracted to Tinseltown's underbelly, its behind-the-scenes work and backstage dramas.

Barron Bailly says Benton also learned more about movie-making techniques and co-opted them. For example, the artist fashioned clay models of characters and scenery that he would light up like tiny Hollywood film sets, then painting them.

“Through those methods he’s able to get a very luminous glow to his canvases,” Barron Bailly said. “There’s a feel of projected light, there’s a feel of three-dimensionality, there’s a feel of motion, of drama, and all of those things we associate with watching movies.”

There’s a replica of a surviving Benton clay model (or maquettes) in the PEM show. The original was too delicate and valuable to ship, so in a first for the museum, curators actually created a 3-D print.

“Visitors will be able to touch it and appreciate the fact that Benton once said, 'I feel my paintings in my hands,'” Barron Bailly said, smiling.

For Wall Street Journal art reviewer Lance Esplund, the 3-D print of Benton’s model is a very effective tool for conveying the artist’s process. His personality comes through in the curation too.

“He's crazy," Esplund said, laughing. "He's got a lot of stuff going on — I mean, he's an interesting guy, certainly."

Esplund says highlighting the artist's links to Hollywood is helping him understand how Benton attained his signature effects in the paintings and murals.

“The drama, the theater lighting has always been evident in his work, but this really drives those points home,” Esplund said after seeing the new exhibition. “And he’s certainly not the first artist, nor will he be the last to be influenced by the camera. But this does put a new lens on him certainly.”

PEM's Barron Bailly says the artist’s relationship with the “dream factory” approached a climax in 1940 when 20th Century Fox studio head Darryl Zanuck hired him to create art to promote director John Ford’s adaptation of “The Grapes of Wrath."

“There’s a real recognition that his ability to get to the kind of quintessence of a character or a scene,” she said.

Benton made black and white lithograph portraits of each character from the film, along with imagery of the Job family's iconic departure from their farm. The film studio blew them up for posters to celebrate the controversial movie's New York premiere. Barron Bailly says Benton's style also inspired the aesthetic John Ford and his team created in the final film.

Also in 1940, Benton and about a half dozen other top artists were invited to the set of “The Long Voyage Home,” also directed by Ford and starring John Wayne. The producers commissioned them to paint images for a marketing campaign — or publicity stunt, depending on who you ask.

Benton’s last Hollywood commission was for the 1955 Technicolor film “The Kentuckian." It was a passion project for Burt Lancaster, who directed and played the main character.

“It was fun as a child to meet people like Marlon Brando and Burt Lancaster, and Jimmy Cagney was a great friend,” Benton’s daughter Jessie told me on the phone from Kansas. The 76-year-old says her father would appreciate the new exhibition.

“It’s like a thumb in the nose to his critics of his own time,” she said.

And Benton has had plenty. He’s been called everything from a cartoonist — not a painter — to a drunk to a racist for depicting white actors in black face and the Ku Klux Klan.

“I think it’s fantastic to bring daddy back — but daddy is not just murals and Hollywood,” Jessie Benton added. “He’s also intimate portraits, and people he knew, and interests he had, which were so incredibly varied and enormous. He never stopped working, ever.”

Except, perhaps, when his family vacationed on Martha's Vineyard every year. In fact, Benton actually worked until the day he died in 1975 — paintbrush in hand.

And the 20th century artist still has fans in Hollywood today. Rob LaZebnik, writer and producer for "The Simpsons," is lending a Thomas Hart Benton drawing he found at an art fair in L.A. to the new exhibition.

“American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood” is at the Peabody Essex Museum through September 7.