Advertisement

First Look: ‘Science Behind Pixar’ Debuts At Boston’s Museum Of Science

The remarkable thing about "The Science Behind Pixar," the exhibition that makes its world debut at Boston’s Museum of Science on June 28, is that it feels as wondrous as the California company’s animated films. The exhibit is like a magician revealing the illusions—and still you marvel at the slight of hand.

“Walt Disney, when he started, was inventing feature telling film with animation, but at the same time was based upon what was the brand new technology of the time,” says Ed Catmull, one of the founders of Pixar and now president of the company as well as of Walt Disney Animation Studios. “And every time something new came out—whether sound or color or xerography—he adopted it. Then when he died all this went away. What people didn’t realize was that it was the infusion of the changing technology with the art that caused a mutual exchange of energy between the two.”

“When computers came in—and originally it was Roy Disney Jr. [Walt’s nephew] who brought Pixar into the picture” at Disney, Catmull says. “He actually understood this and so we entered into a relationship to bring technology into animation. And for Disney, that was to help with the hand-drawn animation, which is what we did do. But at the same time, we had been working for years on 3D animation. The result was this amalgamation of the artists with the technical people, with this incredible cross-fertilization that continues to this day.”

So “The Science Behind Pixar” is not the sort of exhibit that insists that “Cars” offers important lessons in physics or “Finding Nemo” is full of insights into marine ecology. Thankfully. Rather, the exhibit is deeply and honestly rooted in how Pixar turns algorithms and digital code into dazzling cartoon worlds. It convinces that—despite what you may have (erroneously) been led to believe—math and computer science are not intimidating or tedious; in the hands of Pixar wizards, mathematical equations are magic formulas.

Catmull is a great representative of Pixar’s merger of art and science. “My belief,” he says, “is that it’s actually the mixture of the two that is what causes things to move forward.” He studied physics, computers and art in college. His first piece of computer animation, according to Karen Paik’s 2007 book “To Infinity and Beyond: The Story of Pixar Animation Studios,” was a 3D rendering of his hand opening and closing that he made in 1972. He personally helped pioneer many of the foundational concepts of computer animation.

“Our very first film was ‘Toy Story,’ which was the first computer-animated [feature] film,” Catmull says. “But the characters basically were plastic. So over the years, we had to figure out, OK, how do you make skin on a human look right, or how do you make foliage look right, or hair.”

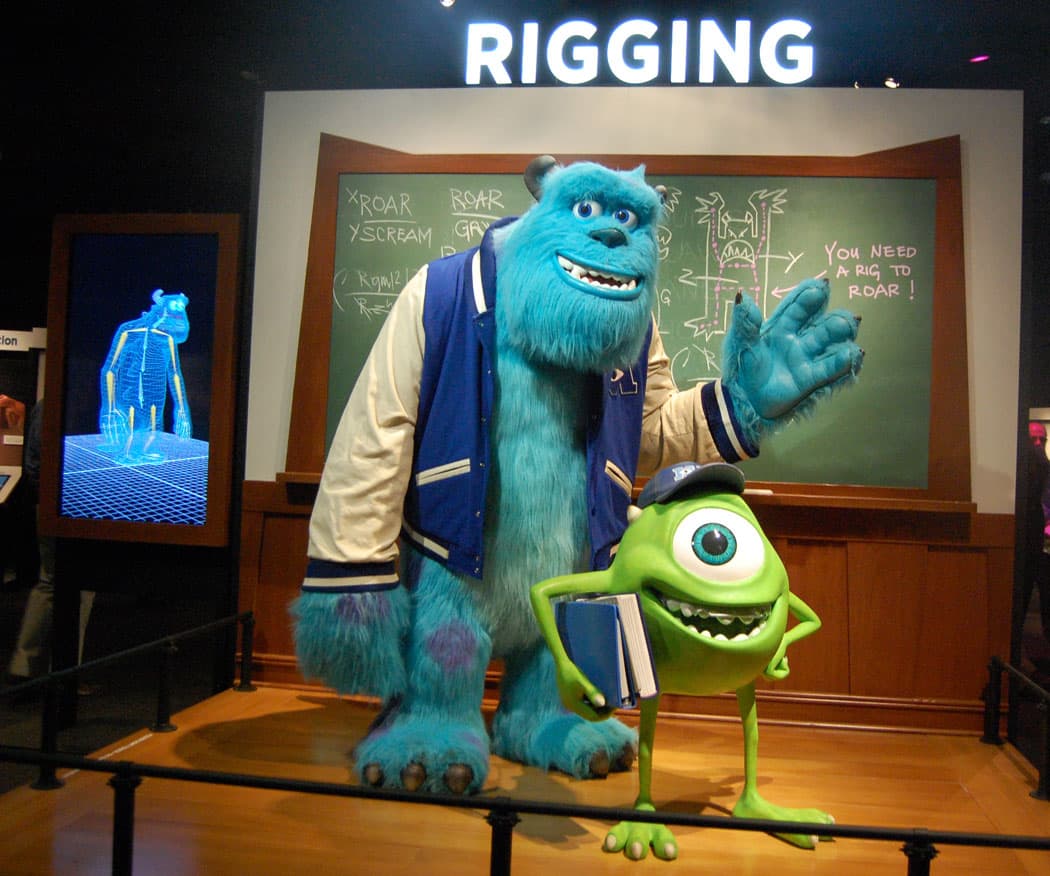

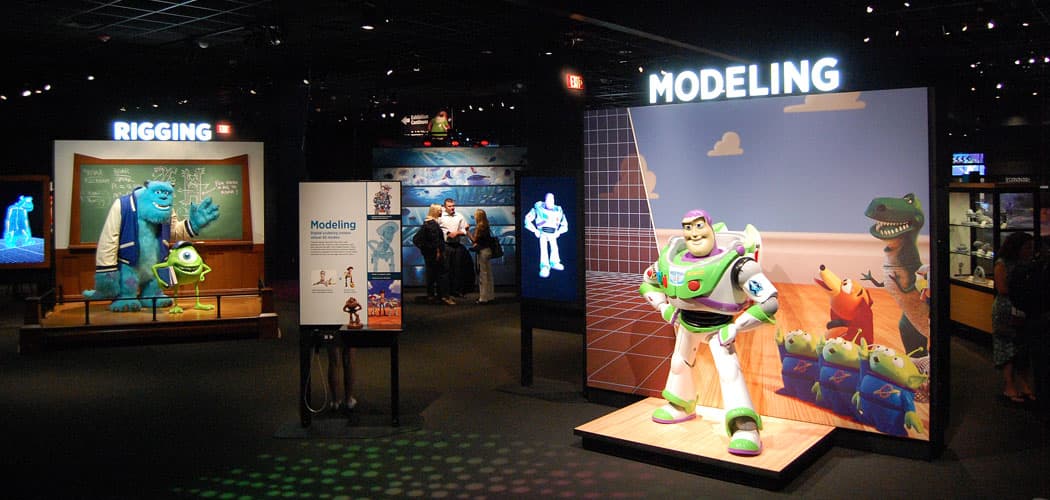

“The Science Behind Pixar,” an original collaboration between Pixar and the Museum of Science, continues through January, before heading off on a five-year, 10-city tour. The initial wows when you enter the show are the larger than life-sized statues of Buzz Lightyear from the “Toy Story” films, Sulley and Mike from “Monsters, Inc.,” Dory from “Finding Nemo,” Wall-E from the eponymous film and Edna Mode from “The Incredibles.” Mainly these are prompts to take out your camera and pose with old friends.

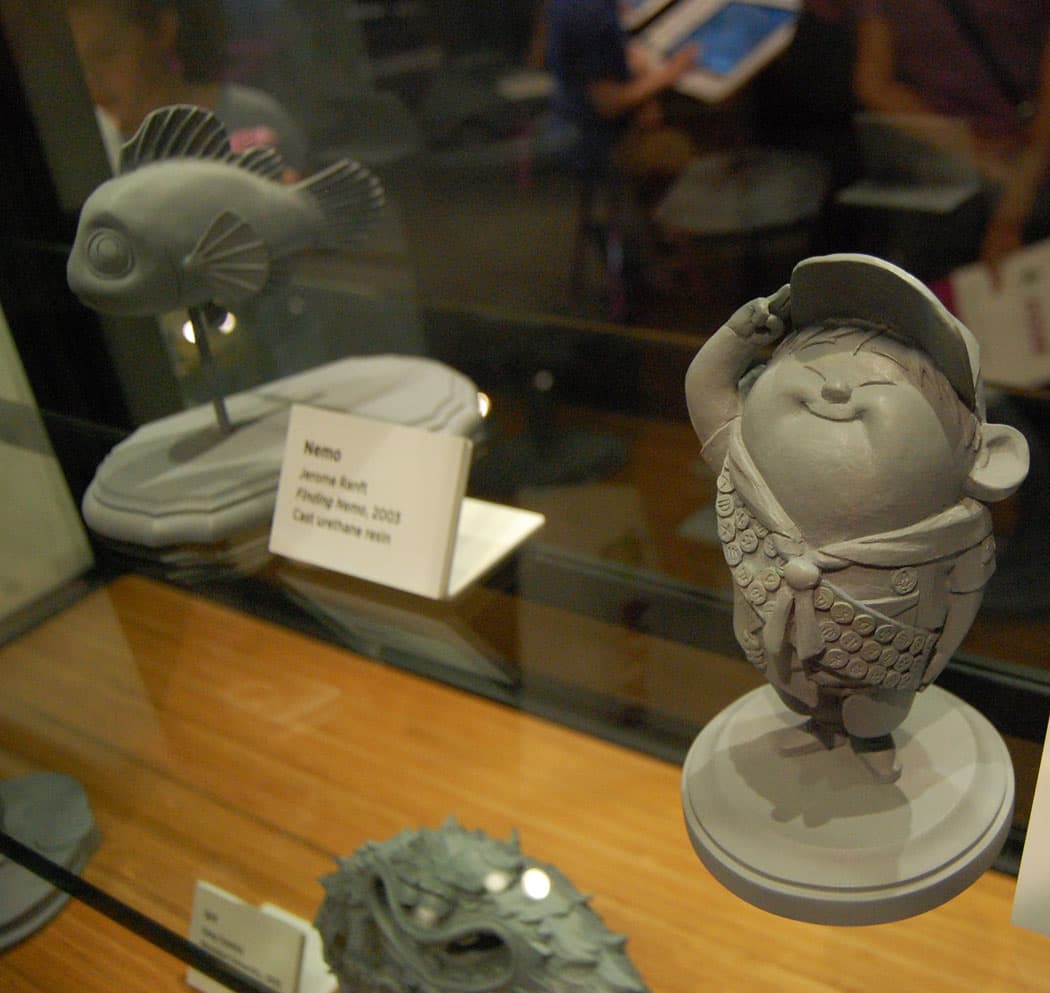

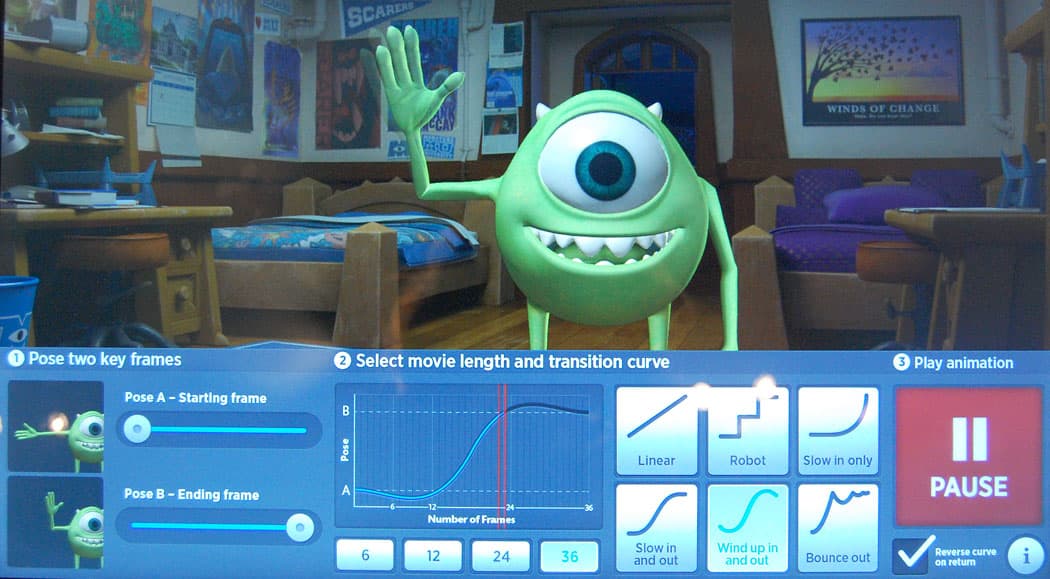

The focus of the show isn’t original cartoon art (except for a case of sculptural character models), but dozens of hands-on activity stations that demonstrate different camera shots, stop-motion animation, lighting effects, how computer programs simulate movement and the mathematical formulas that the studio uses to, say, grow all the grass in “Brave”’s virtual Scotland. There’s an impressive clarity to the way concepts are modeled. For example, to explain how Pixar digitally wraps shapes in different skins and virtual textures, the exhibit offers a metal wedge that you can physically wrap in different fabrics that make it resemble a slice of watermelon or a hunk of cheese.

“The purpose of the exhibit we’ve got here in Boston is to say that there’s a tremendous amount of creative science and math and perceptual issues, just a whole gamut of scientific issues that are part and parcel of what it takes to make the film,” Catmull says. “And if we’ve done a good job, the audience never even thinks about it. What we are trying to do is celebrate it and say, OK, these scientists and mathematicians are an integral part of what we’re doing. Not just because they’re providing tools, but because they’re stimulating the storytellers and the artists.”

“The Science Behind Pixar” is geared toward kids (including, in my experience, children as young as 2) and families. Physical manipulatives (robot models to build, cameras to control) as well as more complex operations controlled by touch screens engage a range of ages. One of the smartest aspects of the exhibition design is that there are two to three copies of nearly every demo station, which means everyone gets to try each particular one out sooner.

Will grownups have fun? I attended a preview at which plenty of adult couples seemed to be having fun dates. And if you’ve never quite understood how Pixar works its magic, this is an amazing primer.

Greg Cook is co-founder of WBUR's ARTery. Follow him on Twitter @AestheticResear or on the Facebook.