Advertisement

Harvard Film Archive Revisits Robert Altman's 'Popeye'

A lone drifter arrives in a ramshackle town. The locals regard him with suspicion at first, slowly warming to his oddball nature despite what seems to be the guy’s lifelong habit of always making the wrong enemies. He becomes smitten with a woman way out of his league, but she coyly withholds her obvious affections. A confrontation is brewing between this misfit hero and a sinister criminal organization aiming to bleed this sleepy little village dry — a showdown for which our man may very well be outmatched. The soundtrack is loaded with melancholy songs from a 1970s troubadour and the dialogue mixed so low and mumbly you can barely understand a damn word anybody is saying.

Sure sounds like “McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” Robert Altman’s breathlessly acclaimed 1971 revisionist Western masterpiece that, arriving just a year after his boisterous surprise blockbuster “M*A*S*H,” cemented the director’s reputation as a freewheeling, counter-cultural muckracker of American malaise. It’s a downright legendary picture, and in 1999 Roger Ebert wrote: “Altman has made a dozen films that can be called great in one way or another, but one of them is perfect, and that one is ‘McCabe & Mrs. Miller’.”

But here’s the thing, I was talking about “Popeye” — Altman’s critically despised, big-budget musical comics adaptation that’s mistakenly been consigned to the dustbin of cinema history and too often shows up on ill-informed lists of Hollywood’s biggest box office bombs. (The movie actually turned quite a tidy profit in theaters, plus an astonishingly lucrative home video run that continues to this day.) Still, so toxic was the 1980 reception of “Popeye” that Altman was left unemployable and exiled to Paris, directing micro-budgeted indie theater adaptations for the remainder of the decade.

Reputation be damned, “Popeye” — showing this weekend in an extremely rare 35mm print at the Harvard Film Archive as part of their “The Complete Robert Altman” series — is a wonderful movie, beguiling and deeply strange. It’s also a stealth remake, as was discovered a few years back when DigBoston critic Jake Mulligan and I found ourselves temporarily unencumbered by relationships or gainful employment and often stayed up all night watching old movies together. Revisiting “Popeye” for the first time since our childhoods at 3 in the morning (some chemical enhancement may or may not have been involved) the realization hit like a thunderbolt: “Dude, this is ‘McCabe’ for kids. Isn’t it?”

That’s the great thing about Robert Altman, there was no subject nor any genre that he couldn’t somehow turn into a Robert Altman movie. Other filmmakers tell stories, Altman created ecosystems. He built minutely detailed worlds, mostly governed by sadness and systemic corruption, and then sent his iconoclastic heroes ping-ponging off the walls of their limitations, often failing spectacularly — think of the drafted doctors in “M*A*S*H," lashing out at rigid military discipline and a pointless war by behaving as childishly as humanly possible, or Elliott Gould’s anachronistic white knight in “The Long Goodbye,” bebop-muttering his way through a broken Hollywood dream factory.

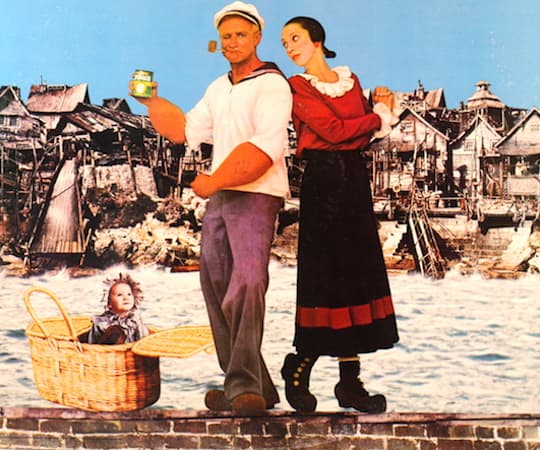

Robin Williams’ Popeye The Sailor Man may indeed be based on the boldly-drawn icon from E.C. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” and the more famous Max Fleischer cartoons, but he’s still an Altman hero through and through, sputtering a running commentary under his breath rife with malapropisms and disgust-ipated with a world gone mad. Popeye arrives in the island village of Sweethaven not to set things right, but the sheer force of his no-guff personality necessitates doing so. “I yam what I yam,” he exclaims — defiantly, heroically.

And what a place this is! Bordered by shipwrecked schooners, it’s an impeccably designed, falling-apart community lorded over by an evil, unseen Commodore on a distant boat who has a tax collector following everybody around making up random fees with which to gouge the populace. Bluto, The Commodore’s 320-pound, 6-foot-4 enforcer calls curfews and sings entire songs about how mean he is. (He’s mean.) Every piece of wood holding together the town’s complex arrangement of bridges and streets appears to be rotting from demoralized decay.

Sweethaven is a cartoon come to life, but Altman doesn’t shoot it in the stylized panels of a comic strip. He films it like Nashville in “Nashville” and just lets a roving camera amble, zooming around as if capturing a documentary. With most of the supporting cast filled out by members of the Big Pickle Circus doing crazy stunts in the far background, this matter-of-fact approach only escalates the movie’s strangeness quotient.

“Popeye” is a weird hinge between 1970s gutter realism and 1980s glossy artifice. Williams’ “squinky-eyed” sailor pines for Shelley Duvall’s Olive Oyl (talk about someone being born to play a role) but they spend most of the movie arguing. In his first starring role, Williams is already in a league of his own, tamping down his crazy standup and Mork from Ork routines, fully committing to the peculiarity of this character and delivering a complete, oddly tender performance. He’s a three-dimensional cartoon.

Eventually, alas, they ran out of money. Altman always favored filming his movies far away on locations where homebody Los Angeles producers and studio babysitters would never venture out to look over his shoulder. Shot on the barren island of Malta (the movie’s set is still a tourist attraction), “Popeye” was a notoriously decadent production. “We were on everything but skates, and then they sent the skates in and things got interesting,” Williams euphemistically quipped.

Nowadays we’ve got nothing but comic adaptations from major studios, motivated more by franchise management and corporate branding than any artistic aims. Ang Lee’s cockamamie “Hulk” adaptation was probably the last time a real artist would be trusted to go for broke with this sort of valued intellectual property.

So we are left admiring the betting parlors and brothels of Sweethaven. I love it when Popeye enters the latter and advises everyone not to touch anything for fear “you’ll gets a venerable disease.” (Eagle-eyed viewers may spot a lady of the night posing in front of a mirror with an opium pipe, just like the last time we see Julie Christie in “McCabe & Mrs. Miller.”)

“Popeye” is so strange and oddly enthralling, a reminder that however big-budget and seemingly easy the assignment, Robert Altman could only ever make prickly Robert Altman movies.

He was what he was.

Over the past 16 years, Sean Burns’ reviews, interviews and essays have appeared in Philadelphia Weekly, The Improper Bostonian, Metro, The Boston Herald, Nashville Scene, Time Out New York, Philadelphia City Paper and RogerEbert.com. He stashes them all at splicedpersonality.com.