Advertisement

Commentary

The Cultural Roadmap Needs To Head Downtown

It seems as if the downtown arts scene is doing its own version of "The Walking Dead."

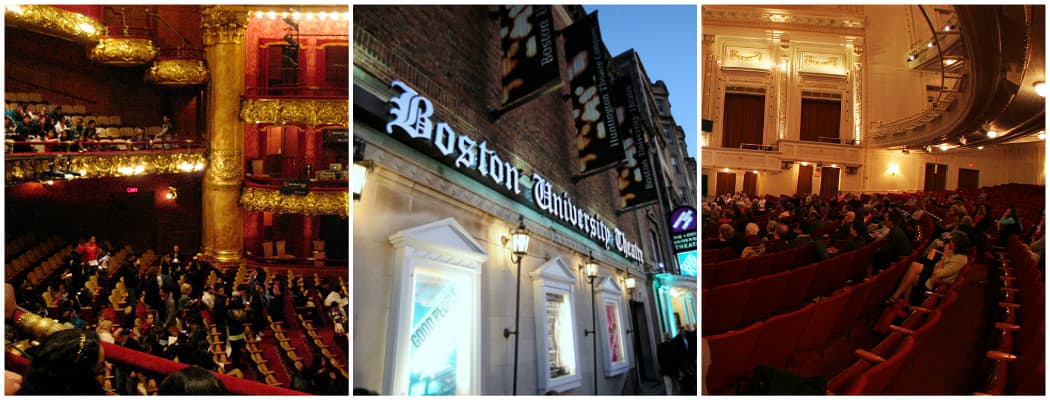

One day it’s Citibank withdrawing its funding from the Wang and Shubert theatres. Boston University parts ways with the Huntington Theatre Company and won’t sell them the property because the Huntington didn’t come up with enough money. Emerson College has a plan on the table to turn the Colonial Theatre into a flexible dining hall/performance space. Then the Boston Lyric Opera announces its plans to leave the Shubert.

But there’s an upcoming event worth noting on the city arts' schedule. On Nov. 2, the mayor’s chief of arts and culture, Julie Burros, will host a Boston Creates Town Hall meeting at Bunker Hill Community College, as part of a plan to develop a cultural roadmap for the city.

As money begins to be disbursed, probably to small cultural organizations, Burros and Mayor Marty Walsh need to reroute part of that roadmap downtown to the Theater District and uptown to Huntington Avenue. It’s time for the two of them to make their presence felt amid the chaos.

UPDATE: The town meeting has been moved to Nov. 2, 6-8 p.m. at Boston Latin School. Mayor Walsh will attend. The post has been updated to reflect this.

I’m not talking about funds. The city of Boston does not have much money to spend on matters cultural. But it has plenty to say about how Boston is laid out, and the city needs Walsh and Burros to start talking in a very loud and clear voice.

In an interview Wednesday, Mayor Walsh said that he and his staff are concerned about the issue, and that they'll be addressing it, but thought that his powers only went so far. They do, but there are still ways to exercise influence.

Think of it this way. Walsh and others, when they ran for the office, promised to do more for the arts in Boston than the late Mayor Thomas Menino did. But thanks to Menino, the Paramount Theatre, the Modern Theatre and the Opera House were saved from demolition, and the Huntington was able to get a second stage within the Calderwood Pavilion, which it also operates. The Strand Theatre in Dorchester was given new life.

As Maureen Dezell wrote in The ARTery two years ago, “In 2002, Menino did one of the things he’s known to do best: called, convened, pushed, prodded, rewarded and froze out the right people at the right time, keeping all interested parties at the table until a deal to bring the Opera House back to its original splendor was done that fall. The city put zoning and building permits and other approvals on a fast track and the theater reopened with a touring production of 'The Lion King' in July 2004."

Although every situation is different, Walsh needs to step into Menino’s shoes and make sure that the energy and commitment that Menino put in place is not diminished.

This is more than a matter of helping large institutions. Without the Huntington’s stewardship of the Calderwood, the SpeakEasy Stage Company would not have grown from a small theater to such an important midsize one. Company One Theatre would probably not have grown from the fringe to one of the best theaters in Boston.

As Jane Chu, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Boston Foundation's Paul Grogan and the Barr Foundation's James Canales have said, there is an ecology to an arts scene. And the health of large institutions is important to small ones as well.

What can Walsh do without the millions of dollars it will take to turn all these situations around? Most importantly there is the bully pulpit. Trigger alert: Mayor Walsh needs to be a bully and say:

“The most beautiful theater in the city, maybe in the country, is not going to become a cafeteria on my watch. The Huntington is going to stay where it is. And Boston needs a real opera house.”

The Colonial

How much sense would it make if the blood, sweat and tears that went into saving the Opera House resulted in the loss of the Colonial? Broadway Across America — Broadway in Boston locally — would most likely still be booking the Colonial on a regular basis if the Opera House hadn’t been revived.

Broadway Across America has a near monopoly on front-line touring shows, and because of the high cost of big-budget theater both in New York and elsewhere, road company versions of shows are limited to safe musicals. Other entities scrape by with leftovers, like second and third runs of musicals, which don’t give them the cushion that’s needed to provide robust competition to Broadway Across America. That means that Broadway Across America doesn’t need to get out of its comfort zone of safe musicals.

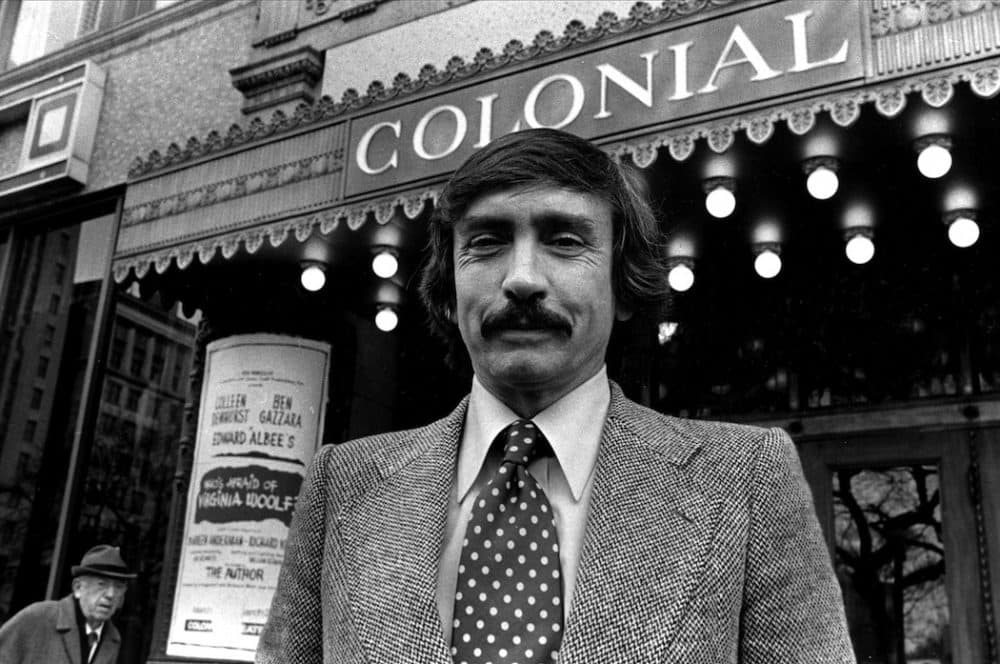

About five years ago, Emerson asked New York producer Jon Platt, who restored the Colonial in the '90s, to run the theater, in hopes that he could bring more adventurous fare from New York and elsewhere, but Platt said at the time that Emerson was putting too much financial pressure on him to make it work.

It should be noted that Emerson has been a terrific Boston citizen in helping to restore the Paramount and the Cutler Majestic Theatre. Emerson has also been a generous patron of ArtsEmerson, which has brought such thrilling theater from around the country to Boston, and given some local organizations like Company One an occasional home at the Paramount.

Still, the college knew when it bought the land that the Colonial stands on that it was also buying stewardship of a landmark theater. Walsh needs to remind them of that stewardship in no uncertain terms, even going as far as saying that “With all the tax breaks that colleges get in this city you don’t want to make an enemy of me.”

At the least he and/or Burros should cajole all the interested parties to the table, maybe even arbitrating a deal between Emerson and Platt or a like-minded curator of the space, and come up with a plan for the Colonial. Bring in architects; Catherine Peterson, head of ArtsBoston; Julie Hennrikus of StageSource; Josiah Spaulding of the Wang and Shubert; labor unions; foundations and other interested parties; and see what alternatives there are to cheeseburgers. There has to be a place for the institution beyond the mixed-use black-box theater and cafeteria that’s on the table (pardon the pun).

People have noted that the Colonial is dark 75 percent of the time. I’m not the greatest math whiz in the world, but that means it’s still lit 25 percent of the time. It should be more, sure, but it’s hardly a dead space and with some creative thinking could be lit a good deal more.

The Huntington

BU might want to sell the theater to the highest bidder as it moves its own student theatrical operations to Commonwealth Ave. In truth, BU has not gotten as much out of the relationship as it might have hoped. BU students aren’t particularly present in Huntington productions. The Huntington mainstage is actually housed at the BU Theatre, but almost everyone refers to it as the Huntington Theatre. And why not. It’s not at BU, but on the outskirts of Northeastern on Huntington Ave., where it is one of the cornerstones of the Avenue of the Arts, along with Symphony Hall, Jordan Hall and the Museum of Fine Arts.

It’s clear that the Huntington wants to stay there and partner with someone to buy the property. But what if someone else wants to turn the whole site into condos? Says Michael Maso, managing director of the Huntington, “The answer to condos in a development project is not a straightforward one. Public amenities play a role in the development process and in what gets built in any site. I am a firm believer in including the Huntington in any development plan, and that there will be more money to be made for that developer with the Huntington there.”

Does the mayor have a role? “The city government,” says Maso, “has a role to play in every development plan in the city.”

So, yes, Walsh should loom large in any discussion of the Huntington staying in that space. But the fact is that no matter what happens, the Huntington will most likely be homeless after 2017 for a year or two, as the space needs to be modernized. The Colonial, at 1,700 seats, roughly twice the size of the BU Theatre, is too big a space to be a permanent solution for the Huntington. But for a year or two? Perhaps with one or both of the balconies closed off for more intimacy?

Mayor Walsh needs to tell Lee Pelton, president of Emerson, “Hold the pasta station, Mr. President. You can’t say no one will be using the space if the Huntington will be the tenant for a year or two.”

The Wang And The Shubert

Josiah Spaulding, who was booking the Colonial for the last few years, has not been the major player he once was in Boston theater, partly because there isn’t the “product” there used to be when he and Platt were competing against each other in the '90s. Spaulding, whose base was the Wang, took control of the Shubert and booked the first touring production of “Rent” for a long-term run. Platt, then running the Colonial, responded by getting the Wilbur for a long-term run of Faye Dunaway in “Master Class.” (The Wang looks back this Friday with an open house, kicking off a yearlong celebration of the theater.)

Those long-term runs aren’t feasible at the moment. Now the Wilbur is part comedy club and music venue; the Wang features music acts higher up on the food chain than the Wilbur; the Shubert has lost the Boston Ballet and Boston Lyric Opera.

The Shubert would therefore be another alternative for the Huntington while things progress on Huntington Ave. or elsewhere, which is something else that Walsh could help broker if it makes more sense than the Colonial.

Boston Lyric Opera

The Shubert was never a great venue for the Boston Lyric Opera. It wasn’t built for opera; the pit and the acoustics have been a longstanding problem. It’s good to have the organization downtown, but it hasn’t led to the kind of artistic growth that the company should be enjoying.

The BLO seems confident that it has better options for the future but is being somewhat coy as to what they are. Could there be business to be done with the Huntington, which has hosted operas in the summer? Or, I should say, the BU Theatre has. The Boston Ballet, too, might prefer to be in a space that had more flexible dates than the Opera House.

I can’t see the two sharing the same space, particularly given the BLO’s problems with the Shubert and the Huntington’s need for a full-time space. But what about a complex, perhaps on Huntington Ave. with side-by-side buildings, as in the successful Playhouse Square in Cleveland?

Here’s what the New York Times had to say about that collaboration between arts, real estate developers and civic leaders:

"Playhouse Square’s residential project may provide a model for other struggling Rust Belt cities that are eager to find the synergy that links the performing arts, urban development and affordable commercial real estate.

'The basic rule in real estate for 5,000 years is value is tied to location,” said Robert L. Lynch, the chief executive of Americans for the Arts, a nonprofit arts advocacy organization in Washington. “Whenever you can do something that enhances a location, you enhance the value. Art and theater are value enhancements.' ”

But why look to Cleveland?

We've already seen dramatic change in the South End and downtown, spurred by the Calderwood and Paramount — and Mayor Menino. A complex housing the Huntington and BLO could do the same for Huntington Ave. (though hopefully with more affordable housing).

Could you imagine such a complex on Huntington Ave.? Why not?

Why not, indeed, Mayor Walsh?

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Broadway Across America's relationship to the Opera House. It rents, rather than owns, the building.