Advertisement

A Loving Look At The Late Pierre Boulez, The Incandescent Master Of Modernism

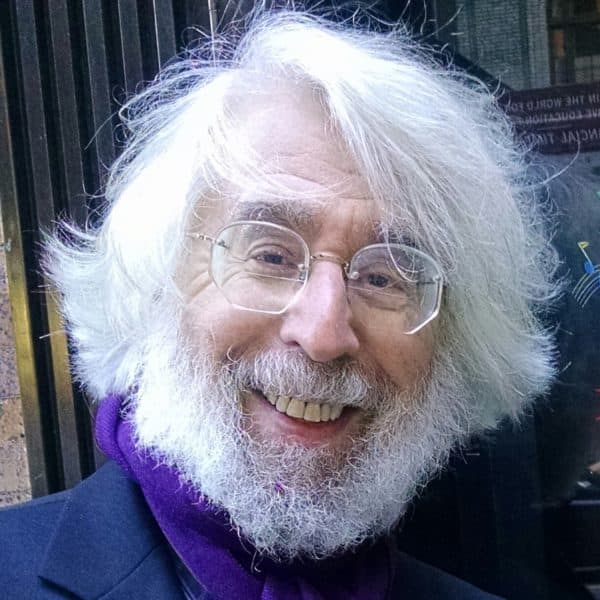

Pierre Boulez, who died on Tuesday at the age of 90, wasn’t just a composer or a conductor. He was in many ways the voice of — and for — the modern world. He was the eye that saw it and the ear that heard it. He had what the Germans call a “Weltanschauung” — a world view.

A bold avant-garde composer who never thought anything he wrote was ever completely finished (the recent Deutsche Grammophon box of his complete works is subtitled “Works in Progress"), he became an astonishing conductor, famous mainly for his performances and recordings of 20th century music. His Bartók Concerto for Orchestra with the New York Philharmonic, for example, is a revelation — no other performance I’ve ever heard comes anywhere near.

But he also became a major conductor of Mahler and Bruckner, and for those of us who had friends with tapes of his radio broadcasts with the New York Philharmonic (which he directed from 1971-1977, in a concert hall designed to make anyone with Boulez’s ear extremely unhappy) or the Cleveland Orchestra (for which he was a regular guest conductor), he was also an incandescent conductor of Mozart, Schubert and — so help me — even Dvořák. I’ve tested friends by playing his lilting live performance of Haydn’s last symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic (now available on a Vienna Phil Haydn CD set) and they couldn’t believe it was led by someone not born in Vienna. His Beethoven Fifth Symphony is weird — those famous opening four notes are almost perversely slow; but it’s unforgettable, conducted as if even though every other conductor had exhausted its possibilities, there was still something new and daring to say.

People who didn’t like him thought him a cold fish — but still praised his ear. No one heard and conveyed even the most complex textures as exquisitely, as transparently, as he did. And no conductor alive had such an intuitive sense for rhythms that made everything he played come instantly alive. When he conducted you heard the music.

I’ve just been listening to my old Nonesuch LP of Boulez conducting Stravinsky’s "Le Sacre du Printemps," with the National Orchestra de la RTF (the French national radio and television orchestra), released in 1964. Its visceral power is overwhelming (so much for cold fish). And so is the sense of profound mystery. That LP also includes Stravinsky’s enchanting Four Etudes — a completely different Stravinsky. I can’t remember now whether this was my very first Boulez experience. My other LPs from that era were Boulez’s own first major breakthrough work, "Le Marteau sans maître" (the hammer without a master --inspired by poet René Char), with its lean, acerbic, yet colorfully inventive sound world — and Handel’s "Water Music"!

Boulez started out as a firebrand. In the 1950s, his call (less radical than metaphorical) for blowing up the opera houses had an unforeseen consequence when four decades later, after the 9/11 attacks, the 75-year-old maestro was dragged from his hotel room by the police and arrested for being a terrorist suspect. “All the art of the past must be destroyed,” he announced after the death of Stravinsky. Yet, there he was on Dick Cavett's late-night TV show, the music director of the New York Philharmonic and soon-to-be founder of France’s IRCAM (Institute for the Research and Coordination of Acoustics and Music), allowing himself to be tested on his perfect pitch (the host kept asking someone in the orchestra play a note and asked Boulez to identify it, which he repeatedly and graciously did).

Far from being cold, he was a charming and welcoming conversationalist. I felt very lucky to have met him and talked to him on numerous occasions. In London a few years ago, I was on a queue at Albert Hall, waiting to pick up tickets for a concert he was conducting, when he walked by and waved at me! He knew, of course, that I admired him above just about all other living musicians — even at a time when it was fashionable to attack him. I always wondered if the people who called him cold, intellectual and mechanical had ever actually listened to his performances.

Then he started winning Grammys.

In celebration of his 90th birthday, major collections of Boulez recordings have been reissued. Both Sony and Deutche Grammophon have issued huge box sets of Boulez conducting. There’s a complete Mahler box, a 20th Century music box, and complete sets of the recordings he made between 1956 and 1967 with Le Domaine Musical and his recordings on the Erato label (mostly avant-garde international 20th Century music, including Elliott Carter, Birtwistle, Grisey, and of course some Boulez). Plus the complete DG set of his own “works in progress.”

If I were to encourage someone who didn’t know Boulez to check him out, I’d suggest the DVDs of Wagner’s complete "Ring Cycle," a stunning souvenir of the performances he first led at Bayreuth, staged by the late Patrice Chéreau, on the centennial of the cycle in 1976 (and videotaped in 1979-1980). It’s a stunning production — one that actually deals with the moral, political and economic issues raised in the opera. Boulez’s conducting is the heart of it. The pacing is swift, but nothing goes unheard. The music moves in waves, surging, plunging, retreating, then resurging. There are even pianissimos. It’s consistently gripping, absolutely mesmerizing and deeply moving. I’ve never seen a production that unwinds so relentlessly, so compellingly. Boulez is the great conductor of such modern masterworks as Debussy’s "Pelléas et Mélisande," Berg’s "Wozzeck" and "Lulu," and Janáček’s "From the House of the Dead" -- and his Wagner seems to carve a direct path to those extraordinary works.

Boulez’s own music has the daring qualities of his conducting, yet unlike some musicians who compose on the side, Boulez’s own challenging music — mostly serial, without the foothold of melodic repetition and occasionally using electronics — is central to his whole enterprise. Probably his best known pieces, besides "Marteau sans maître," are his three Piano Sonatas. I’m a big fan of his elegant string quartet, and the fabulous and much-revised flute concerto with electronics “…explosante-fixe…” (a memorial to Stravinsky, quoting Stravinsky’s memorial to Debussy).

Who could resist his scintillating early "Notations" for piano or his later (breathtaking) expansion and orchestration of them? It’s amazing that a seductive short piece like "derive" could evolve into a monumental work like "derive II." His short piano piece "incise" became one of his most ambitious, alluring and evocative works, "sur incise," with its uncanny combination of three harps, three pianos and three percussion instruments. Here’s an excerpt:

I heard him conduct in Boston four times. In 1986, while the BSO was on tour, Boulez led the contemporary music chamber orchestra he founded, the Ensemble InterContemporain (in those days the group capitalized the C to emphasize the portmanteau pun joining “international” and “contemporary”), in two shake-up-Boston concerts at Symphony Hall. The first was an all-Boulez program, in which the seats on the floor were removed so that folding chairs could surround the platform on which the musicians played "Répons," a piece uniting electronics and traditional folk instruments like the Hungarian cimbalom. The following week’s program, in a more conventional arrangement, included music by Varèse, Schoenberg, and the Boston premiere of Elliott Carter’s knotty and mysterious "Penthode." A couple of weeks later he was back leading the BSO for the first time since 1969. The program was Stravinsky, Boulez ("Notations"), and by far the most refined and intense live performance I’ve ever heard of that BSO staple, Ravel’s "Daphnis and Chloe."

In 1998, Boulez returned to Boston as part of a remarkable event — a special concert combining players and conductors of the BSO (Seiji Ozawa), the New York Philharmonic (Boulez), the Cleveland Orchestra (Dohnányi), and the Cincinnati Symphony (Masur) to help raise money for the prohibitively expensive rehabilitation of BSO manager Ken Haas, an affiliate of all four orchestras, who had suffered cardiac arrest that resulted in a serious brain injury. Boulez opened the program with a brilliant Dukas fanfare and magical, shimmering, transparent performances of the “Nuages” and “Fetes” movements of Debussy "Nocturnes."

I think the last time I spoke to him was in 2010, during the Berlin Philharmonic’s two-week celebration of his 85th birthday (imagine something like that happening here for a living composer). He said that some of the pieces being played seemed very old to him. And that he seemed old to himself. Yet in the one program he himself conducted (“…explosante-fixe…” and Stravinsky’s opera "Le Rossignol" -- a piece he said he had loved since his childhood), he had all his customary precision, passion, and youthful energy.

Here’s a clip from that very concert:

In 2003, as composer Tod Machover, who worked with Boulez at IRCAM, describes it, Boulez “launched the Lucerne Festival Academy to give the best young music professionals an opportunity to create, perform and understand new music with an unparalleled mix of rigor and radicalism, the two qualities that Boulez always embodied.” “Tradition is mannerism,” he told the Harvard Music Department at a symposium on French Modernism in 2003. “The desire to please at any cost is something I am deeply suspicious of,” he told the Boston Globe’s classical music critic Richard Dyer in 1986. “The desire of the artist must be to communicate, not to please.” Pierre Boulez was a revolutionary, a visionary, a monumental figure, a great musician, a hero of our time. His loss is a profound one.

More On Boulez:

Lloyd Schwartz is a music critic for NPR’s Fresh Air and senior editor of Classical Music for New York Arts. Longtime classical music editor of The Boston Phoenix, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 1994. He is the Frederick S. Troy Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Follow him on Twitter at @LloydSchwartz.