Advertisement

The Nobel Prize Goes Electric — Bob Dylan Takes The Prize In Literature

In a year of consummate outsiders, a man who draws as much sustenance from Hawaiian ukulele music as the Oxford Anthology of Poetry is this year’s winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. And what an inspired choice it is.

Bob Dylan has spent the better part of 70 years breaking down boundaries and those who are complaining that Dylan’s work isn’t literature sound as hollow as the folkies who booed when he went electric.

Dylan’s lyrics rarely stand alone on the page as well as, say, Leonard Cohen’s, but when they do they’re unsurpassed, as in his white-hot mid-‘60s period. Take “Mr. Tambourine Man”:

Then take me disappearin’ through the smoke rings of my mind

Down the foggy ruins of time, far past the frozen leaves

The haunted, frightened trees, out to the windy beach

Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow

Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free

Silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands

With all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves

Let me forget about today until tomorrow …

And that isn’t really the point. A common definition of literature I’ve found in a couple of places is: “Writings in which expression and form, in connection with ideas of permanent and universal interest, are characteristic or essential features."

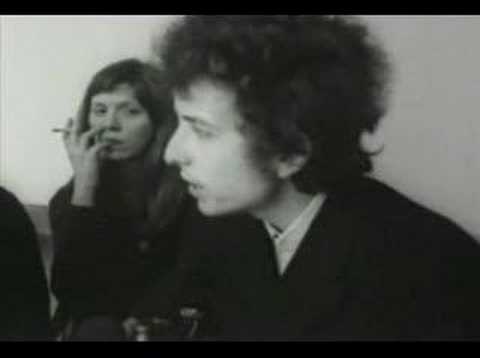

“Expression and form” are the keys there. Some folks prefer Dylan’s lyrics sung by, say, Joan Baez or Garth Brooks, but Dylan wasn’t just whistling “Dixie” (a song he covered) when he told a Time magazine reporter “I’m just as good a singer as Caruso.” It’s at the six-minute mark of this excerpt from “Dont Look Back”:

If anything, he was underselling his singing abilities. Ray Charles may have had the only other voice in music, popular or classical, that conveys as much lyrical history. In Dylan’s case you can hear beat poetry, the blues, rabbinical sermons, Christian gospel, anti-authoritarian protest, country and western music of all kinds, Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly folk music, wry narration and even short story writing in songs from “Bob Dylan’s 115 Dream” to “Desire” and, most recently, “Tempest.”

Lately he’s incorporated the American songbook into his cavalcade. Nobody’s going to confuse his singing with Sinatra’s, but as his voice has aged into a growl it’s also grown into something warmer and more embracing, and the emotional directness of these songs must speak to him on a profound level.

He’s also signaling a kinship with some of the great songwriters of an earlier time, like Harold Arlen and Jimmy Van Heusen. But even Cole Porter isn’t “literary” in the sense that Dylan is. When you add up the lyrics, the voice and the musical accompaniment from The Band to the great backup groups he’s traveled with since 1997's “Time Out of Mind” there is an artistic story to be told that goes beyond songwriting.

Dylan has morphed from folk and protest singer to beat poet, Woodstock dropout (before there was a “Woodstock”), rueful returner to the world at large with “Blood on the Tracks,” depressive drug user, born-again Christian, lost soul in the ‘80s, and finally to the looming eminence grise he’s become since “Time Out of Mind.”

As I said about his most recent writing after the Tanglewood concert last summer: “These story-songs generally tell the tale of an artist sadly, but wryly, looking at a world gone wrong — levees breaking, leaders lying, lovers cheating, workers reeling.”

It’s a Homeric odyssey that’s led from a righteous '60s embrace of changing the world to a more challenging view of 21st century decadence, accompanied by his own romantic search for love among the ruins.

Is it literature? You bet, even though he couldn’t care less what you call it. Remember his jibes about “the old folks’ home in the college.” That he’s made this journey to the accompaniment of a rock ‘n’ roll beat only makes it, and him, the more remarkable.

The poet Michael McClure once wrote in Rolling Stone about bumping into late media theorist Marshall McLuhan at a Dylan concert. “McLuhan believes that rock & roll comes out of the English language — using its rhythms and inflections as a basis for melody … The future of rock, he felt, would be the same as that of the language; that it would have ups and downs as the language does.”

That language — in all its aspects — has been in great hands when it comes to the Nobel Prize-winning artistry of Bob Dylan.