Advertisement

Cambridge Writer Tells Of Little-Known 1941 Belcher Island Murders In 'At The End Of The World'

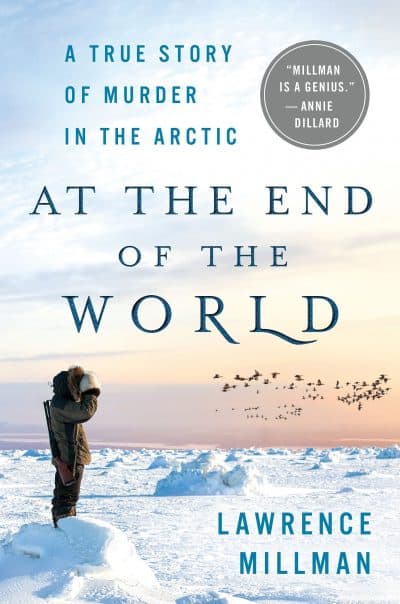

In "At the End of the World: A True Story of Murder in the Arctic," Lawrence Millman tells the little-known tale of a horrific series of murders in Canada's remote Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay in 1941. In recounting the story of a short-lived but intense religious fervor that turned a close-knit of band of Inuit against one other, Millman also aims to warn readers about what he sees as a modern fervor for tech devices that turns people away from the natural world. However, a self-righteous tone on all things digital makes his argument veer wide of the mark.

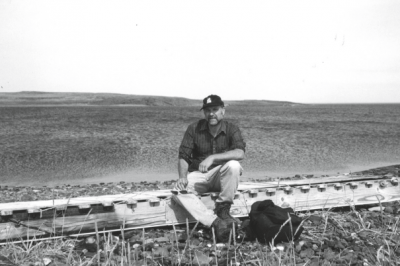

Millman, a Cambridge resident, is the award-winning author of 11 travel books, as well as numerous travel articles in magazines such as National Geographic, Sports Illustrated and Smithsonian. In this book, he notes the power of telling stories, and that for "At the End of the World," he realized, "I couldn’t write about the past without also writing about the world immediately around me."

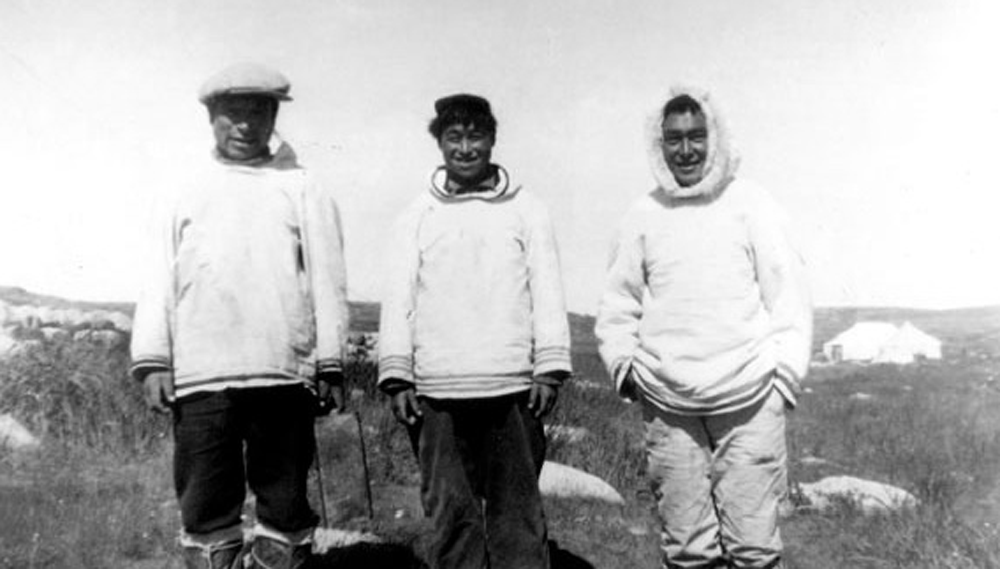

The winter of 1941 was a harsh winter even for northern Canada, and especially so for the Inuit on the Belcher Islands. The remote archipelago, just below the Arctic Circle, offered very little vegetation even in warmer months, and that winter there were few seals or walruses or even arctic hares for the Inuit to hunt. The residents spent long nights inside their igloos, sometimes reading translated copies of the New Testament portion of the Bible, brought to the Belcher Islands just a few years before by traders and missionaries.

One night during this bleak season, a spectacular meteor shower illuminated the skies. One man, 27-year-old Ouyerack, connected the celestial event with a passage from Matthew: “the stars will fall from the sky… and [you] will see the Son of Man coming.” His interpretation? Soon, it would be the end of the world.

Ouyerack considered himself an “angakok” (a shaman), and considered Jesus “the white man’s angakok.” After the meteor shower, Ouyerack proclaimed himself an Inuit Jesus, saying, “I am Jesus Christ preparing the people for when the other Jesus comes.” He named Peter Sala, the islands’ best hunter and ice navigator, as God.

The two men painted an uplifting vision of a fabulous life, fast approaching, that would be free of hunting, fishing, work, and hunger. At the same time, they ordered most of the sled dogs killed (no need for sled travel at the end of the world, and also fewer means of escape for nonbelievers).

Blending old and new religions, Peter told his fellow Islanders that even though he looked the same on the outside, on the inside he was God. The Inuit believed that everything in nature — people, animal, rocks, rain — had a soul, and that a soul of any kind could travel from one being to another. A person might still look the same on the outside, but could now have a completely different spirit.

When a teenage girl disagreed that Peter was God on the inside, he declared her to be Satan. Her half-brother, a zealous follower of the two self-anointed men, brutally murdered her. Soon after two men, nonbelievers, were killed. In March of that year, six people died in one day, frozen to death, after Peter’s sister Mina, believing that Jesus’ arrival was imminent, herded men, women and children onto ice in the harbor, and ordered them to strip off their clothes so they could meet their Savior naked.

Millman tells this tale in a free-flowing narrative style, interspersing his interviews of the remaining survivors and their relatives with a history of the region (including a sardonic account of the filming of the 1922 documentary "Nanook of the North" on the mainland), a liberal peppering of quotes from diverse authors on nature and on technology and the consequences of old and new cultures clashing. News of these crimes finally reached the mainland, and the principals were tried and convicted by a Canadian judge and a six all-white male jury later that year.

For this subject matter, the raconteur style works only part of the time. In his zeal to depict digital technology as the (not so) new dangerous religion, he often loses the thread of the main story, leaving the 1940s narrative often and abruptly to fume about how today we shun the real world for the virtual one.

There is some validity in comparing tech worship to religious fervor, and there have been numerous books and articles in recent years that have sounded the alarm on how our devices are changing us. But in “At the End of the World” Millman weakens his case by including too many self-congratulatory anecdotes of him being the only person in a conversation not staring at or anxiously checking a digital device. He also makes breezy, sometimes dubious, assumptions about technology use, as when he theorizes that people like to watch movies on smart phones because "[maybe] they get a sense of superiority by observing minuscule members of their own species?"

Millman’s casual tone, perhaps unintentionally, reduces certain tragedies — the 1941 Belcher Island murders, 9/11 and the Boston Marathon bombing — to simple springboards for anti-computer rants. For example, Millman was returning to Cambridge in 2013 after area towns had been on lockdown as police pursued the Boston Marathon bombers. He became distressed to learn that many acquaintances had spent most of their enforced time at home on their laptops. He flippantly posits, in a tone jarringly at odds with the circumstances: "It’s an exaggeration, but not much of one, to say that most of those residents would have remained indoors anyway."

Ironically, in a book about the dire consequences of religious fanaticism and about the difficulties of letting in elements of a new culture without completely losing the old, Millman’s own passion about “climate-controlled” citizens who “fear the natural world” too often engulfs a story that is both unique and that may well have some cultural connections to today.

Lawrence Millman is speaking at Porter Square Books in Cambridge on Tuesday, Jan. 17 at 7 p.m.