Advertisement

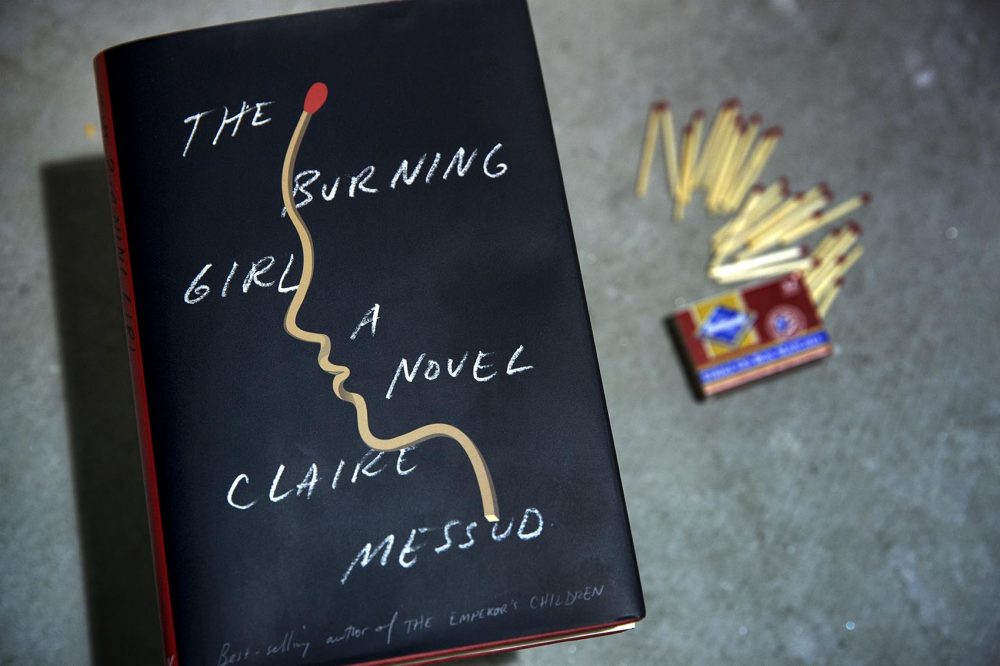

Claire Messud's 'Burning Girl' Forces Us To Recognize How Perceptive Teens Could Be

“I’m always at the edge of the circle,” says acclaimed author Claire Messud.

The observer on the periphery is a position familiar to writers and also to adolescents, and it’s the vantage point from which high school senior Julia Robinson paints the mysterious coming-of-age tale in Messud’s latest novel, “The Burning Girl.”

Julia recounts troubles that one might expect of a plot that starts in middle school years: an unrequited crush, coming to terms with her parents’ expectations for her future and the estrangement from her dear childhood friend, Cassie, which stands at the center of the story. This narrator, however, is not ordinary, even for an outsider.

This narrator, however, is not ordinary, even for an outsider.

She relays the events that haunt her formative days in small-town Massachusetts with the drama and confidentiality one might expect of a teenager’s diary, but her ability to articulate what is happening to her, and how it feels, has a precision one might expect from an older, more experienced protagonist — or a practiced storyteller. For example, as Julia, Cassie and their peers grapple with distinguishing grim hallway gossip and fairy-tale imagination from true danger, Julia observes, “Sometimes I felt that growing up and being a girl was about learning to be afraid... You came to know, in a way you hadn’t as a kid, that the body you inhabited was vulnerable, imperfectly fortified.”

In granting the teenage narrator this verbal acuity, Messud might sacrifice some verisimilitude in exchange for access to the full range of her own skills, but the choice also forces readers to recognize how perceptive a person of this age can be.

“Young people know what they experience,” the author and mother of two teenagers says. “They have the insight, but they don’t necessarily have the words to say it.”

In many ways, Julia’s emotional intelligence drives the plot. Her sense of intimacy with or alienation from her peers and the adults brings them into sharp focus at times, and at others plunges them into shadowy suspicion. When it comes to the central crisis, Cassie’s disappearance, Julia reconstructs her lost friend’s story vividly, based partly on second- or third-hand information but even more so on what she trusts as a heartfelt understanding of what the girl who had been like a sister to her experienced. We’re compelled to believe her, not in spite of but because of the narrator’s youth, because of her uninhibited ability to know and say what she feels so deeply and acutely.

The effect is captivating, and in some ways the outcome vindicates Julia’s intuition. At the same time, neither Julia nor readers can deny that, at its root, the story on the page is at least in part an invention of the teller’s mind. Julia explores frankly some of the circumstances that might place her in that privileged position over her friend. In her fictional hometown of Royston, the haves and have-nots live close together, but class plays a big part in the extent to which they are expected to live — or leave — on their own terms. Julia’s traditional nuclear family, her parents’ white-collar jobs, and her academic success all seem to set her on a path for a promising future, and Cassie’s lack of that security seems to inevitably put her at emotional and physical risk. Even if Cassie’s actions are her own, we only know them in Julia’s words.

Or perhaps the privilege of the storyteller works the other way around. Maybe Julia’s tendency to skirt the outside of the adventure, to insulate herself in observation, keeps her safe. The risk only comes later, when she re-opens the tale and confronts the truth that her own power has limits, too. “Whatever choices we think we make, whatever we think we can control, has a life and a destiny we cannot fully see,” she says.

Readers of the “The Burning Girl” might like to think that we can venture to the edge of the story and feel its intensity, but remain with our hands coolly gripping the pages. We might do well to consider Julia’s warning, “That I can sense the way the plot will go ... it's only an illusion I cling to.”

Claire Messud will be in conversation with Radio Open Source's Christopher Lydon at the Brattle Theatre on Tuesday, Sept. 5.