Advertisement

A Homicidal Patricia Highsmith? A Heroic Samuel Beckett? 2 Novels Take A Smart Look At 2 Artists

It’s not exactly a new literary form, but the idea of making a writer the main character in a novel, namely Samuel Beckett and Patricia Highsmith, proves to be a unique way of looking at these two iconic artists. In many ways it brings you closer to them and their work than biographies of the two great writers.

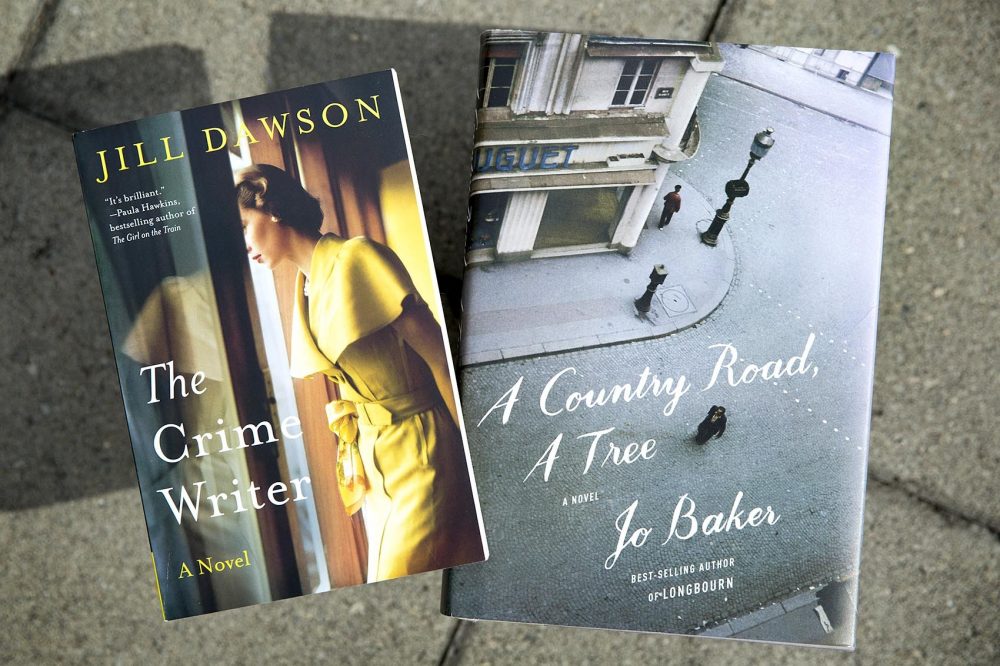

Both now available in paperback, Jill Dawson’s “The Crime Writer” imagines Highsmith as a central character in a murder mystery while Jo Baker’s “A Country Road, a Tree” takes a deep dive into Beckett’s years in the French Resistance. Both are, at the least, finely-written pageturners and, at their best, a means of humanizing their charismatic subjects.

“The Crime Writer” is the more fun of the two, which isn’t surprising because, well, crime writing is more fun than being on the run from Nazis or confronting the abyss. But “A Country Road” is the more insightful — you might not think of “Waiting for Godot” in the same way again.

Dawson and Baker don’t try to ape their subjects’ style, but summon up their worlds — both literary and experiential — to tell stories that Highsmith and Beckett would likely have appreciated, combining a thematic echoing with biographical detail, as in Beckett and his lover on the lam in a way that evokes the two major characters in “Waiting for Godot.”

Highsmith was long identified as a crime writer, but Dawson is in part using the title ironically because she detested Agatha Christie and hated being lumped in with the popular crime writers. True, every novel except “The Price of Salt” AKA “Carol” has a crime in it, but not all the short stories do. Highsmith railed at the stereotyping, thinking that her stories were no more crime novels than “Crime and Punishment” or “The Stranger.” Gore Vidal called her “one of our great modernist writers.”

The writer has also gained recent attention for “The Price of Salt/Carol” her “lesbian novel,” which she wrote under a pen name and made into a terrific film by Todd Haynes in 2015. But if that love dared not speak its name in 1952, Dawson makes up for it in 2017, with Highsmith involved in fairly graphic sex with her lovers.

Dawson places her in a small village in Suffolk, England, where Highsmith did, in fact, hole up in 1964 to write “A Suspension of Mercy” and “Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction.” “Mercy” is one of Highsmith’s odder books in that it’s almost a great one, but suffers too much from motivational lapses to be as believable as her other books. Here, too, a writer has retreated to the English countryside with his wife. She’s a painter, but the two artists seem to be most creative at getting under each other’s skin. When she goes missing has he killed her or is he imagining her death as a plot device?

Which is the similar device that Dawson uses in “The Crime Writer,” but with healthy doses of “The Price of Salt” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley” thrown in. Highsmith, herself, is the main character. She’s having an affair with a woman in a loveless marriage, a la “The Price of Salt,” which in turn was sparked by Highsmith’s infatuation with a married woman.

As things get more violent among the triangle we’re left to wonder whether it’s all in Highsmith’s head as she’s plotting “A Suspension of Mercy” and putting her theories of suspense writing into play — or is it real. Highsmith is being interviewed by a journalist, which gives her the opportunity to expound on some of the themes in her books. Are we all capable of murder if provoked? Is there a Tom Ripley beating in all our frustrated breasts?

Writer Alison Bechdel feels capable of murder just reading Highsmith:

Dawson draws on Highsmith’s notebooks as well as two biographies — Andrew Wilson’s excellent analysis, “Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith” and Joan Schenkar’s tabloid “The Talented Mrs. Highsmith.”

Highsmith was not a nice person, to say the least, but reading Schenkar’s book, which got the lion’s share of attention, she is little more than a grotesque. Dawson doesn’t shy away from Highsmith’s negatives, but in this work of fiction you feel that you’re getting to know the woman far better than you do in Schenkar’s biography.

Schenckar gives you Highsmith as seen through the world’s disapproving eyes. “The Crime Writer” shows you the world as seen through Highsmith’s disapproving eyes. It’s a seemingly more realistic, and definitely a more interesting way of knowing what Highsmith is all about as an artist and a human being.

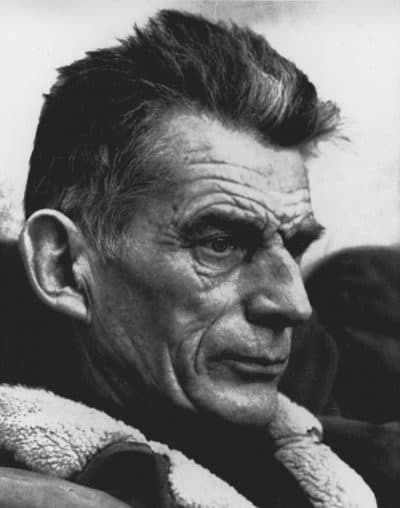

Beckett, meanwhile, comes across as a less austere figure in “A Country Road, a Tree.” Not that he’s a barrel of laughs as Jo Baker catches up with Beckett and his lover, Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil. They are part of the ‘40s artistic expatriate scene in Paris, where Beckett is helping James Joyce with “Finnegans Wake.” Beckett has been writing novels himself, books that evoke Joyce’s style.

It’s his plays, of course, that made Beckett Beckett in the eyes of the world, particularly “Waiting for Godot,” in which two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, wait for a man who will lead them … somewhere? A 1990 National Theatre poll voted it the most significant play of the 20th century. The play is open to all kinds of interpretation, but often it’s seen as a statement of having to go on — “I can’t go on, I must go on” — even though life is essentially absurd, or even meaningless.

“A Country Road, a Tree” takes a different path. Beckett and Suzanne are also waiting for word, but they’re waiting for word of where to go and what actions to take during World War II. Beckett did, in fact, become a member of the French Resistance, but always downplayed what he did for them.

As he and Suzanne trudge along, often starving, often freezing, often looking just to find a safe harbor, Baker is obviously drawing parallels with the “Godot” characters. Survival is paramount and there’s a constant struggle not to give in to despair. There are echoes of Roman Polanski’s great film “The Pianist” (Polanski was also on the run from the Nazis in Poland), in which survival is more a matter of luck and randomness than of heroism.

But if Beckett’s and Suzanne’s actions aren’t heroic they’re hardly meaningless and the choices they make are courageous. This isn’t faceless dread they’re up against, it’s Hitler’s minions. Baker isn’t the first person to draw parallels between Beckett’s wartime experience and “Godot,” but she so convincingly has us walk in his threadbare shoes that it would be hard to see “Godot” after this without thinking of Beckett’s wartime experiences

That doesn’t invalidate other interpretations of “Godot.” As Baker says in her author’s note:

“The war changed Beckett as a writer, and probably as a thinker, transforming him from “an (albeit brilliant) adolescent, overburdened by his influences … those years in occupied France seem to have established many of the key themes, images and preoccupations of Beckett’s later work. They also marked the start of his paring away at language: a stripping back of Joycean wordplay and polyphonic extravagance, towards bare bones, and silence.”

How good are “A Country Road, a Tree” and “The Crime Writer” if you’re not familiar with their works? I think they both hold up well on their own, but it’s hard for me to answer that question, having read all of Highsmith’s novels and seen all of Beckett’s plays in one form or another. What I can say is that I think I know these writers better. In Jill Dawson’s hands, Patricia Highsmith comes across as far more human figure, and in Jo Baker’s novel, Samuel Beckett is far more humane.

I don’t know how much these socially fragile folks would have liked the attention, but Highsmith and Beckett — and their works — are all the richer for it.