Advertisement

Boston New Wave Band Human Sexual Response Promises To Reunite In ‘Fabulous’ Style

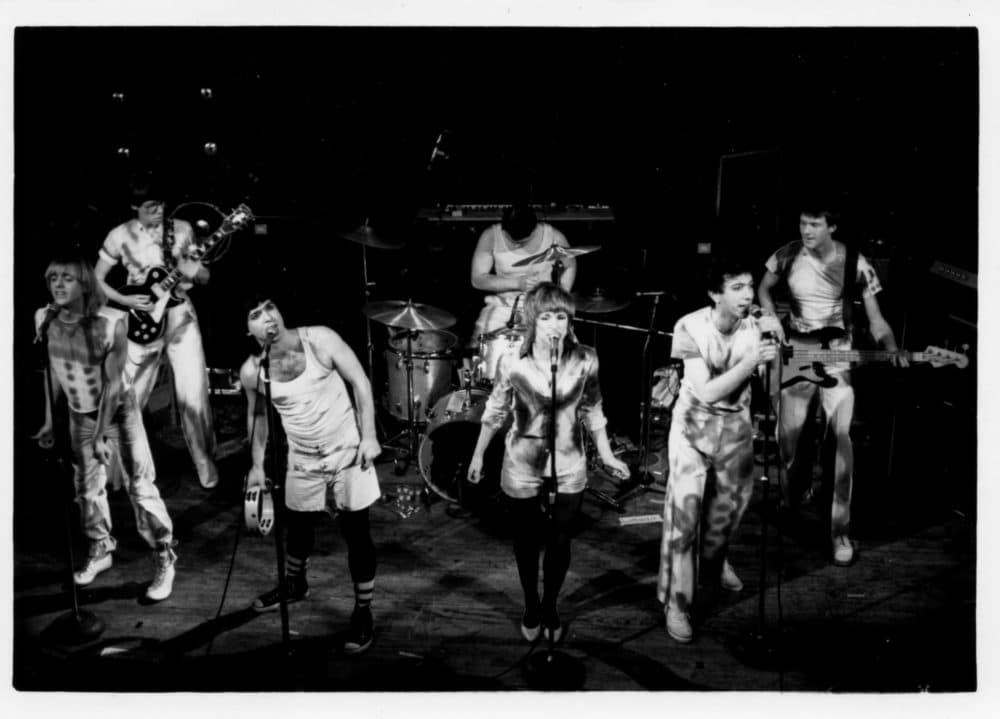

There were a few nights when they took the stage dressed as spiffy, white-uniformed nurses from the 1950s. On another night, they adorned their nearly naked selves with foliage — branches and leaves — causing a breakout of poison sumac on one band member. Then there was the time they bought yards of fabric with Donny and Marie Osmond’s faces plastered all over it and created their stage garb from the cloth.

And there were the Halloween shows, one in Boston and one in Los Angeles, where they did “orangutan outfits.” “We wore black jockstraps and painted our bodies black, with long black tails attached,” says lead singer Larry Bangor. “Except for our butts and our hair, which were bright pink to match.”

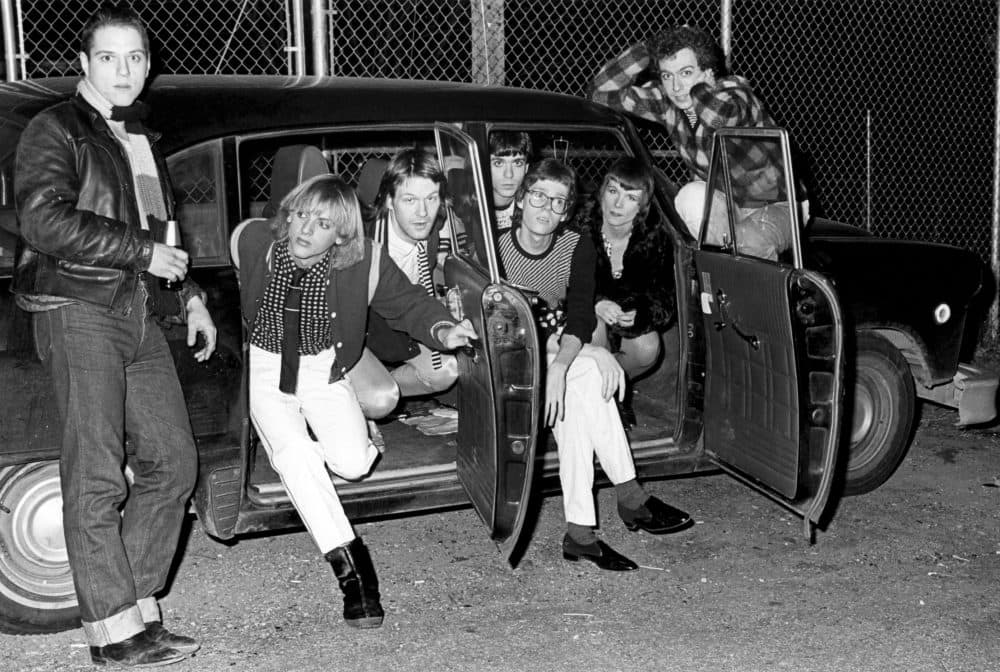

They were Human Sexual Response — six men and one woman, a mix of gay and straight musicians, who became a key part of the Boston new wave scene from 1978 to 1982. They’re back again Friday, Nov. 3 at House of Blues, five years after their last reunion show at the same venue, which was two decades after their previous reunion show.

“We were always trying to make it an event,” says guitarist Rich Gilbert, of the costuming. “Not just for the audience, but for us as well. We really enjoyed making our own costumes and coming up with new ideas, the thrill of it all, making it a real show, not just a gig. Some people did deride us for that. That we were too campy or flamboyant or not true to the punk aesthetic or ideal, but we all loved [Brian] Eno and look at Eno on the cover of that first Roxy Music album.

“We were actually very serious about the band, the music and the material,” Gilbert continues, on the phone from his Nashville home, where the band was about to gather to rehearse. “But once you introduce humor into it — and we definitely introduced humor into our songs and our stage performance — that’s tricky, that’s a tightrope act. Because we had such an unusual stage show and the personalities of the people in the band and even the subject matter of the lyrics, some people immediately dismissed the value of what we did by somehow equating humor in music as being of a substandard quality, which I don’t agree with at all.”

Singer Casey Cameron adds, “We were provocative and we were daring. We could be calculating at times and guileless at others. We had a group dynamic that allowed us to move in a lot of directions at once. We knew we were different from a lot of other bands at the time, and we reveled in that, enjoying the ride, relying on the strength of our determination, laughing with insouciance at ourselves and the society around us.”

No band had a lineup like the Humans. There were four singers: A main singer (Bangor) and three backup/occasional lead singers (Cameron, Bangor’s younger brother Dini Lamot and his then-boyfriend/now husband Windle Davis). Gilbert was joined by a rhythm section comprising drummer Malcolm Travis and bassist Chris Maclachlan (who replaced original bassist Rolfe Anderson).

“Human Sexual Response was just the best new wave band in town, period,” says Maclachlan. “I can say that from an audience viewpoint in 1979. That’s why I wanted to join when the chance came. Human Sexual Response was absolutely, organically right.”

Bangor agrees. “I think we were very much a band of our time. Without the musical and social culture we were part of, we would have been very different, or not have existed at all,” he says. “Since we were who we were, however, the idea of changing or streamlining anything didn’t make sense. We weren't aware of having a multiplicity of styles; we just played how we felt. We played as one instrument — not a lead singer with backup members, not four singers with a power trio.”

The Humans evolved out of Honey Bea and the Meadow Muffins, an a cappella country-western quartet which sang in four-part harmony. “For about a year or more we sang our ‘hit’ song ‘Plain Brown Wrapper’ at parties, outdoor festivals and ice cream parlors,” recalls Cameron. “After a while, we realized we were just fooling ourselves and we really wanted to be in a rock band, so we ditched the glitter cowboy outfits and went over to punk/new wave just as it surged in the late ‘70s. We soon met the musicians, and by 1978, we were Human Sexual Response.”

Looking to assemble a band, they plastered flyers around Boston. “Dini, Windle, Casey and I assembled them together, and stuck them up in music shops and convenience stores,” says Bangor. “It included a nice picture of Patty Hearst, who was at large as Tania at the time.”

That flyer didn’t exactly bring in the right people.

So, they tried again and in a follow-up Boston Phoenix classified ad, Bangor says they took this approach: “In the hope of attracting like-minded musicians, we listed a number of those we admired. I can't remember them all, but it did include Eno, Lesley Gore, Jonathan Richman, The Mamas and the Papas, Bowie, the Chipmunks and the MC5 and Jackson 5.”

The ad piqued Gilbert’s interest — “experimentation, humor, fun,” he thought — and he joined the band, the sizzling hard rock guitarist in the midst of all these swirling, dive-bombing vocalists and these fascinatingly off-kilter songs.

“We didn’t know how to write traditional songs,” Gilbert says. “None of us had ever done it.”

Human Sexual Response made two albums, “Fig. 14” in 1980 and “In a Roman Mood” the following year. The band was nothing if not eclectic. While early Roxy Music might be the best starting point — with its mixture of experimentation, affectation and accessibility — there was also a love of classic Motown, garage rock and art rock.

When I interviewed them en masse in 1981 at a long-gone Boston bar, Bangor described performing one of their more somber songs, "Anne Frank Story," as "never totally serious, nor is it totally a joke — it's somewhere in between." Bangor's sentiment could pertain to the Humans' music in general; at its best, it is rich with undertones and contrast.

In “What Does Sex Mean to Me?” they explored the issue with frank imagery and humor, but also with serious intent, questioning the role sex played in everyone’s lives, including the correlation between the act itself and China’s policy introduced in 1979 limiting family size.

Here's the band performing “What Does Sex Mean to Me?” at Streets, a long-gone club in Allston, in 1982 (video is produced and edited by Benjamin Bergery and Jan Crocker):

With “Andy Fell,” they crafted a crunching riff-rocker with a spine-tingling tragic theme. Andy didn’t exactly fall; he was a student who committed suicide by jumping to his death.

Bergery and Crocker's video of the band performing “Andy Fell” at Streets in 1982:

There was droning, almost industrial rock in “Dick and Jane,” and a virtual mini punk-rock opera in “Dolls.” They could be giddily gay, as in “Butt F---,” and campy, as in “Jackie Onassis,” their “hit.” In the latter, Bangor wrote the lyrics that boasted this opening couplet, sung by Cameron: “I wanna be Jackie Onassis/ I wanna wear a pair of dark sunglasses.” Later in the song, she later pined to fight off autograph hounds, change her name to Jackie K., have her painting done by Andy Warhol and have a doll made in her image.

Here's Human Sexual Response's "Jackie Onassis" in a Bergery and Crocker-produced video:

Stewart Mason, writing for AllMusic.com on the 1991 CD reissue called “Fig. 15,” said: “Far from being a dirtier version of the B-52s, Human Sexual Response were a unique group with an unsettling thematic vision.”

Bangor, who wrote or co-wrote all the material, suggests that perhaps the number of members in the band attribute to their wider range of themes. “Musically a lot of the songs sounded different from each other. But it’s something we noticed more after the fact. It wasn’t like we were trying to cover a lot of territory.”

Gilbert adds, “We knew we were taking a risk with the audience by constantly coming up with material where the next song didn’t sound anything like the previous song. At the same time, it was who we were as creative people. It just naturally came out at that stage of our lives in the band. It was also an era where taking risks, especially in the punk/new wave scene was encouraged.”

Was sexuality an issue? A pro or con?

“I think we ruffled feathers in a lot of other ways more than being gay,” says Bangor, “and everyone in the band wasn’t gay. Also, it was the era when gay and bisexuality was cool — there was no AIDS thing. It gained prominence from the post-Stonewall thing and gay clubs were really hot.”

The Humans had a strong following in the Northeast — Boston, Providence, New York City, Washington and Philadelphia — but Bangor notes they toured the country a number of times and built bases in most major cities.

Still, the Humans didn’t go beyond a certain new wave glass ceiling. Given some breaks — the right record company promotion, the right management, the right timing (they broke up just as MTV entered the world) — they might have had the kind of quirky, but long-term success achieved by Devo or The B-52’s.

“I think very possibly, had we been around during the MTV years, that definitely could have helped us because we had such a visual nature to the band,” says Gilbert. “And we’d probably have had some interesting videos. But who really knows?”

Why the breakup?

“That’s something I really don’t want to go into,” says Bangor. “It’s too complicated. I basically made the decision that I didn’t want to keep doing the Humans.”

Davis is a little more open on the topic. “In 1982, on our way home from a very successful tour,” he recalls. “We were playing a sold-out show in D.C. at the 9:30 Club when Larry confessed to me that he was weary of writing songs for four singers. The band broke up when we returned to Boston.”

After the Humans went down, The Zulus — a more straight-ahead rock band — emerged. It was, essentially, the Humans without the three other singers. They made two albums and broke up in 1992.

Whatever rifts might have existed over the years, Bangor says, “We were best friends and we still are. That’s the amazing thing. We talk to each other all the time.”

The Humans should have at least 25 songs at the ready in Boston, including cover songs they will work up in Nashville. Mum’s the word in terms of costumes, save Gilbert’s promise that “we’re going to look fabulous!” They want it to be a surprise to all.

Human Sexual Response takes the House of Blues Boston stage on Friday, Nov. 3.