Advertisement

Meet Elizabeth Bangs Bryant, A Victorian-Era Spider-Woman Being Celebrated At Harvard

ResumeReed Gochberg was digging through the archives at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology when she stumbled on some striking information buried in some old annual reports.

“What I noticed is that starting in 1869 there's this note that talks about how they've started hiring women as assistants,” she said of the museum's male leaders, “and how they found them to be very good workers.”

Fascinated, the guest curator started piecing together stories and gathering photographs for the online exhibition, “Women of the Museum: Behind-the-Scenes at the Museum of Comparative Zoology.”

One of them was Elizabeth Bangs Bryant. She started as a part-time volunteer in 1898. “And she only began to receive a salary for her work in the 1930s,” Gochberg explained.

Bryant's life-long specialty could make a lot of us squirm.

“She focused on spiders,” Gochberg said, then acknowledged with amusement how the job title “spider curator” provokes a creepy-crawly “eek” response.

Gochberg studies 19th century American culture and the history of museums. Louis Agassiz founded the zoological research museum on the school's campus in 1859. It was a boom time for natural sciences and Gochberg said there were a ton of specimens – fossils, birds, shells, insects – that needed to be cataloged, preserved, labeled and prepared for display. The women listed in the historic ledgers took on those crucial tasks, but Gochberg said they've rarely been given the credit they deserve.

“One photograph I decided to include in the exhibit was of the museum staff, but it's a photograph of all the male curators and professors seated on the steps of the museum,” Gochberg said, “and none of the women are present.”

The invisible roles women have played in science throughout history have been revealed in recent years thanks to books and films including “Hidden Figures.” What Gochberg discovered also reminded her of a parallel story that unfolded right down the street from the zoological museum at the Harvard Observatory. Females there made significant astronomical discoveries as human “computers” while making less than half of their male counterparts.

At the museum Gochberg said, “They were first hired as assistants and secretaries, and sometimes as librarians. But it took a few decades before women started to be appointed at the level of assistant curator.”

Bryant earned her position. Throughout her life she built her own impressive collection of eight-legged specimens on excursions through New England and the Caribbean. Two spiders are even named after her: the Bryantella and the Bryantina.

While she didn't complete her degree at Radcliff because her father died, Gochberg said Bryant kept pursuing her passion with male mentors in her field, including the spider curator at the zoology museum.

Bryant was one of a few women there whose names appear alongside their work. She was also able to get numerous research papers published. But finding information about her personal life has been another matter.

“One of the challenges with Bryant in terms of the available source material I've had so far is that mostly I've been working with her professional correspondence,” Gochberg said, “Although I should say the fact that so many of her letters are in the archives is actually quite notable.”

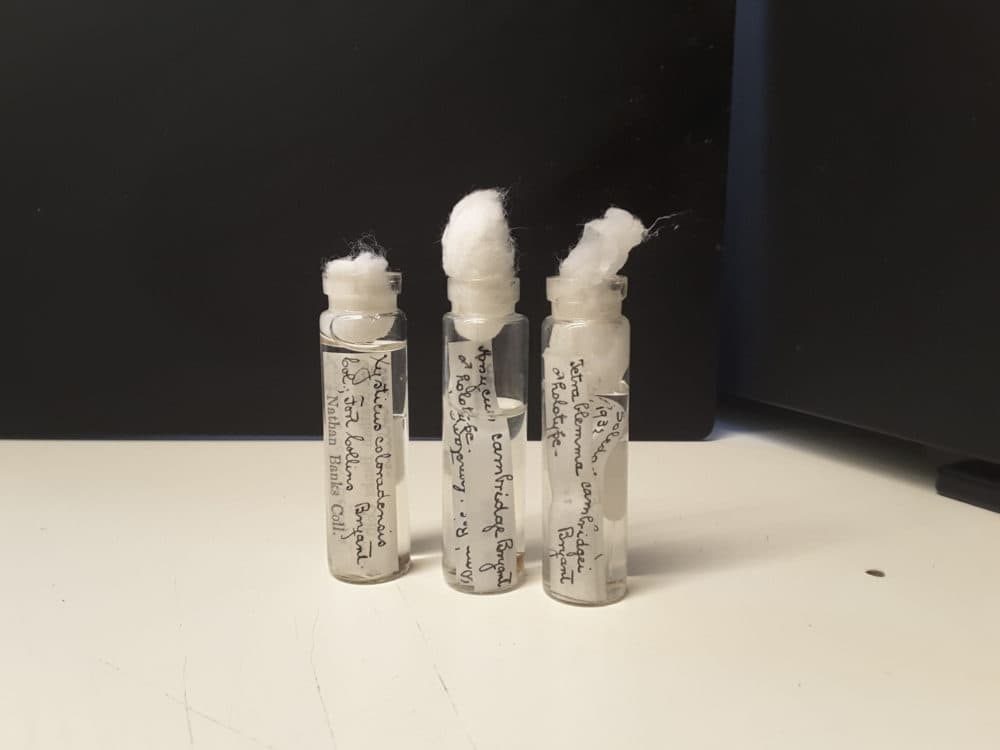

Gochberg said seasoned and aspiring arachnologists wrote to Bryant asking for help identifying the spiders they had collected. They often sent their finds to the museum, and if there were duplicates the assistant curator of arachnids added them to Harvard's holdings.

In Bryant's time women were commonly excluded from the scientific community. When she started her career during the late-Victorian era, they were widely thought to be too frail to endure the stresses of rigorous intellectual work. But Bryant's female correspondents knew otherwise.

“They sometimes will joke with her, talking about men in the field and their dismissal of women who are working on spiders,” Gochberg said.

Bryant's letters offer glimpses of her as a mentor to younger women, but in them she also admitted that refilling vials to preserve the tiny, hairy creatures wasn't exactly riveting.

“She found it often to be very tedious,” Gochberg said, “but she also recognized how important that was in terms of maintaining these collections and making them available to people in the future.”

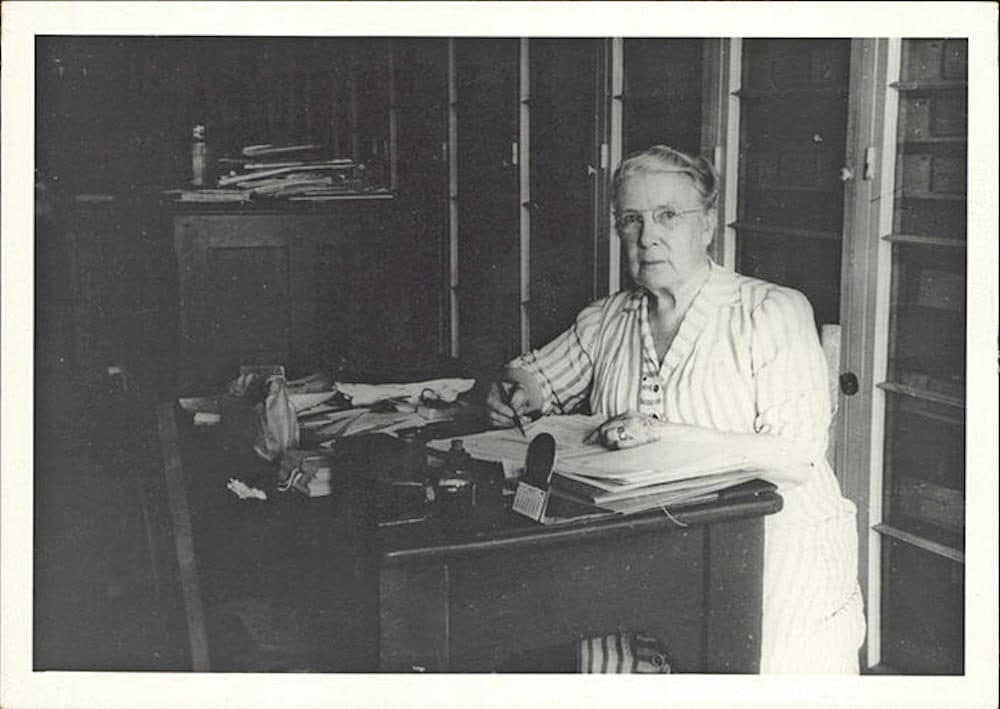

In a photo Gochberg added to the exhibition we see Bryant sitting behind a desk with her pen poised over a notebook – or maybe a letter. She's looking directly at the camera. For years at the museum Gochberg said Bryant cobbled together her own microscopes and earned a reputation as a “thrifty spinster.”

“She was well known for being very frugal and I believe would hand-deliver something in order to save money on a stamp,” Gochberg said. “But she was also known for being a very smart investor. And so the money that she did have, I believe, she invested well enough in order to actually leave a donation to the museum in her will.”

When Bryant died in 1953 she also left her personal spider collection to the museum. Now Gochberg hopes the legacy of this largely invisible arachnologist – along with those of the other pioneering women at Harvard's zoological museum – will help people think differently about who's cared for Harvard's world class collection of shells, fossils, birds, mammals, dinosaur bones and spiders. Today it boasts over 20 million specimens.

Women of the Museum: Behind-the-Scenes at the Museum of Comparative Zoology is presented by the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture.

This segment aired on May 7, 2021.