Advertisement

Hall Of Fame Voters Got It Almost Right. Here's What They Should Have Done

Sorry Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa.

Given your well-publicized and longstanding association with performance enhancing drugs (steroids, for everybody keeping score at home), the Baseball Writers’ Association of America has declined to give you the necessary votes for enshrinement into baseball’s Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

While this is causing much consternation among many chroniclers of the sport, I think the BWAA got it basically right. Cheaters or morally challenged individuals should not be rewarded for their misdeeds.

But I also think the BWAA can go a step further.

The current Hall of Fame is chock full of unworthy players, managers, and executives who should have their bronze plaques removed from its hallowed halls.

Here’s a small sampling of who needs to go:

Ty Cobb

Although he is considered the greatest hitter of the Dead Ball Era (1900-1919) with a lifetime .367 batting average and 4,191 total hits, Cobb was a borderline psychotic who went out his way to alienate fans, opponents, and teammates with his wildly erratic behavior.

“I was like a steel spring with a growing and dangerous flaw in it,” he once confessed. “If it is wound too tight or has the slightest weak point, the spring will fly apart and then it is done for.”

Cobb was a borderline psychotic who went out his way to alienate fans, opponents, and teammates with his wildly erratic behavior.

In 1912 the Detroit Tigers outfielder, who once boasted of killing a man, became so enraged at a fan’s taunts that he bolted into the stands and beat his tormentor viciously. As it turned out, the fan was physically disabled with several missing fingers and therefore unable to defend himself. It didn’t matter to Cobb. “I don’t care if he has no feet,” he said.

Cobb took the same take no prisoners approach on the field. “The base paths belonged to me, the runner,” he later claimed. “I always went into the bag full speed, feet first. I had sharp spikes on my shoes. If the baseman stood where he had no business to be and got hurt, that was his fault.”

He would later get in hot water when he was accused of fixing a 1919 regular season game against the Cleveland Indians with opponents Tris Speaker and Howard Ellsworth "Smokey Joe" Wood. He was eventually exonerated by baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis only after the person making the charge, former teammate Hubert “Dutch” Leonard, refused to make an appearance at scheduled hearings on the subject. Apparently he feared for his physical well being. Such was the reputation of the infamous “Georgia Peach.”

Tom Yawkey

Easily the worst owner in modern baseball history.

After using his inherited millions to purchase the Red Sox in 1933, he spent the next several decades trying to field a world championship team for the Fenway faithful. But the Yale university graduate and longtime South Carolina resident always came up short. Why? It seems that far from being in the racially progressive mold of Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey, who broke baseball’s infamous color barrier in 1947 by bringing Jackie Robinson up to the majors, Yawkey was an unapologetic obstructionist when it came to integration.

Yawkey was an unapologetic obstructionist when it came to integration.

Under his watch, the Red Sox stubbornly dug in its heels and became the last team to sign a black player to their major league roster in 1959. Along the way, Yawkey and his team passed up on the opportunity to sign Robinson and arguably the greatest ballplayer of all time, Willie Mays. In fact, Mays, who clouted 660 homers during his spectacular 22 year career, was considered “not a Red Sox type.”

Yawkey also had no issue with employing managers like Michael “Pinky” Higgins who once boldly announced that there would be “no niggers on this ball club as long as I have anything to say about it.” These bad racial vibes continued even after the team officially integrated.

Pitcher Earl Wilson, Boston’s second African-American player, later revealed to writer Dan Shaughnessy how difficult it was to work in such an environment. Yawkey “had his farmers on his farm,” Wilson said. “They were black. What other people call great is bad for other people. Some people probably thought Hitler was a great person. And they truly thought he was, but they wasn’t Jewish and didn’t have to deal with it.”

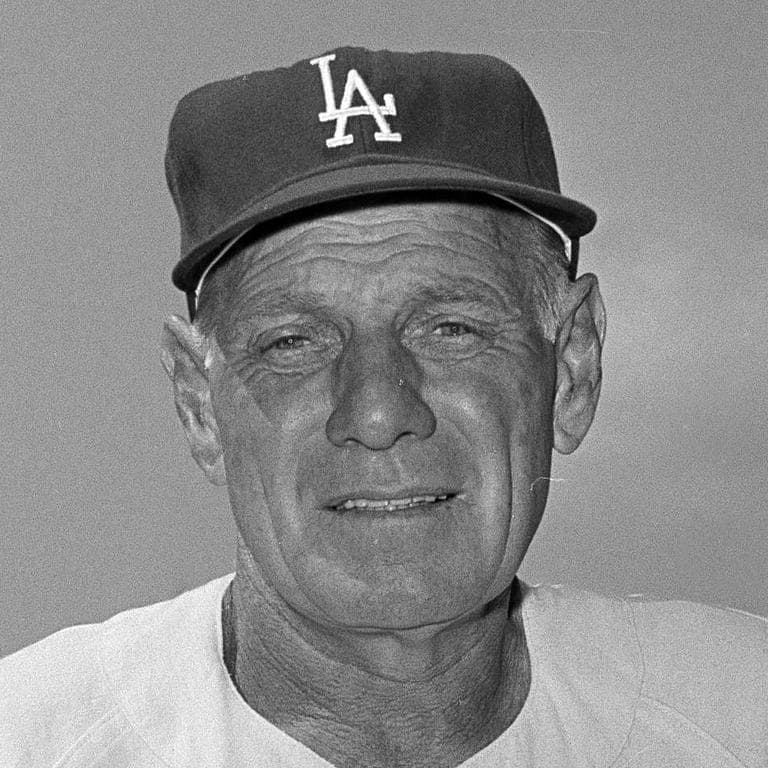

Leo Durocher

This onetime teammate of Babe Ruth made a name for himself by managing the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants to pennants in the 1940s and 1950s. But beyond his proven acumen as a baseball tactician, he had an unfortunate penchant for creating chaos both on and off the field. A precursor to Bobby Valentine, if you will.

Hired and fired several times, the cocky West Springfield native often enraged opponents by ordering his pitchers to throw directly at their heads and engaging in the crudest of bench-jockeying.

For his alleged underworld ties and other perceived sins against the game, Durocher was suspended for the entire 1947 season...

“To tell the truth, I hated the loud-mouthed bastard,” Jackie Robinson once confessed. Indeed, not for nothing was Durocher nicknamed “Leo the Lip.”

Still, this misbehavior paled next to allegations that he consorted too closely with known gamblers and mobsters like Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. For his alleged underworld ties and other perceived sins against the game, Durocher was suspended for the entire 1947 season by then baseball commissioner Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler.

“I believe in rules,” Durocher once said. “Sure I do. If there weren’t any rules, how could you break them?”

Alas, it was this same kind of attitude that probably doomed the induction chances of Bonds, Clemens, and Sosa this time around.

The fictional Roy Hobbs from Bernard Malamud’s 1952 novel, “The Natural” put it best: I guess some mistakes you never stop paying for.

This program aired on January 11, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.