Advertisement

The NFL's Cartoonish Approach To Player Safety

In the ludicrous fines department, this week has been a doozy.

There was the news that the National Football League is taking $10,500 from San Francisco 49ers running back Frank Gore for wearing his socks too low.

But perhaps even more galling, given recent context, was that the NFL docked Patriots quarterback Tom Brady $10,000 on Wednesday for a cleats-up slide [VIDEO] into Baltimore Ravens safety Ed Reed during Sunday’s AFC Championship Game. Disregard for a moment that the play appeared as innocuous as Brady’s leg-lift appeared unintentional and received only a passing comment from analyst Phil Simms.

Against the backdrop of Junior Seau and countless other players like him, fining Tom Brady for reflexively lifting his leg to avoid being hit, is itself the definition of irony.

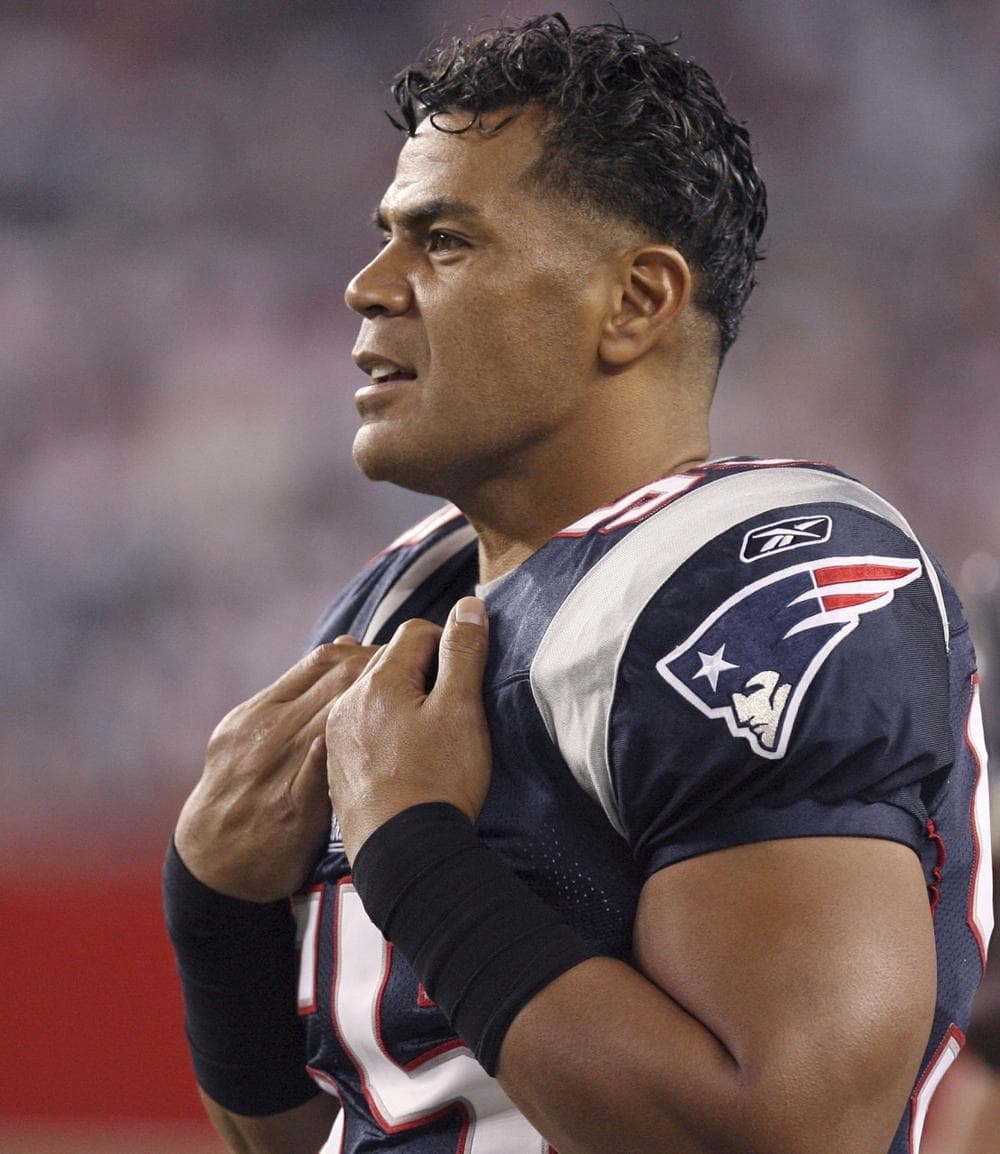

The play and subsequent fine illustrate in cartoonish fashion the inconsistency of the NFL’s rules around player safety. We now know, for instance, that former Patriots linebacker Junior Seau, who committed suicide last year, suffered from a brain illness known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (or CTE), which likely developed as a result of repeated hits to the head over his 20 season career. And here’s the thing: in all that time, Seau was never sidelined with a concussion, despite a former teammate’s assertion that he’d suffered 1,500 or more during his pro career.

Also this week: the linebacker’s ex-wife and four children filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against the NFL for its “acts or omissions” that hid the dangers of repetitive blows to the head. I don’t blame them.

If the NFL can cite Brady for endangering another player with his cleat, why shouldn’t the family of a deceased former player be able to cite the league that sent their loved one into harm’s way, play-after-play, for five times longer than the average player’s career? Because every football play is inherently dangerous, maybe the NFL should fork over ten grand per player, per game for endangering their safety?

Of course, there are many who argue the other side, saying players know what they’re signing up to do and what the risks will be — and are nicely compensated for their work. In other words, football, like boxing, is widely known to be a risky sport, and it is up to the players themselves to decide whether they agree to the risks.

But it is also up to the league to send players onto the (battle) field with the best armor available, so as to minimize the inherent risks. The frightening reality is that Seau played professional football in an era when equipment is better than ever before. Yet despite the state-of-the-art protection, the repeated blows to the head of one of the league’s all-time most-feared players ultimately took their toll.

Furthermore, the arguments from football libertarians are incomplete (at best) because I’d argue these players don’t know the extent of the risks associated with playing football for five seasons, let alone 20. After all, science is just beginning to get a clear picture of the devastating effect the sport has on players’ brains over the course of a career, despite continued denials from the NFL that football causes brain damage.

But the case of Junior Seau should finally put that argument to rest. Against the backdrop of Seau and countless other players like him, fining Tom Brady for reflexively lifting his leg to avoid being hit, is itself the definition of irony. Attaching to the citation “player endangerment” amounts to stupidity in a sport that thrives on hard hits and risky play.

In the wake of the recent brain trauma scandal and the impending exodus from youth football programs, the NFL’s survival depends on its ability to radically transform itself — perhaps removing tackling altogether — instead of pretending idiotic fines and impotent rules actually address the problem.

Related:

This program aired on January 25, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.