Advertisement

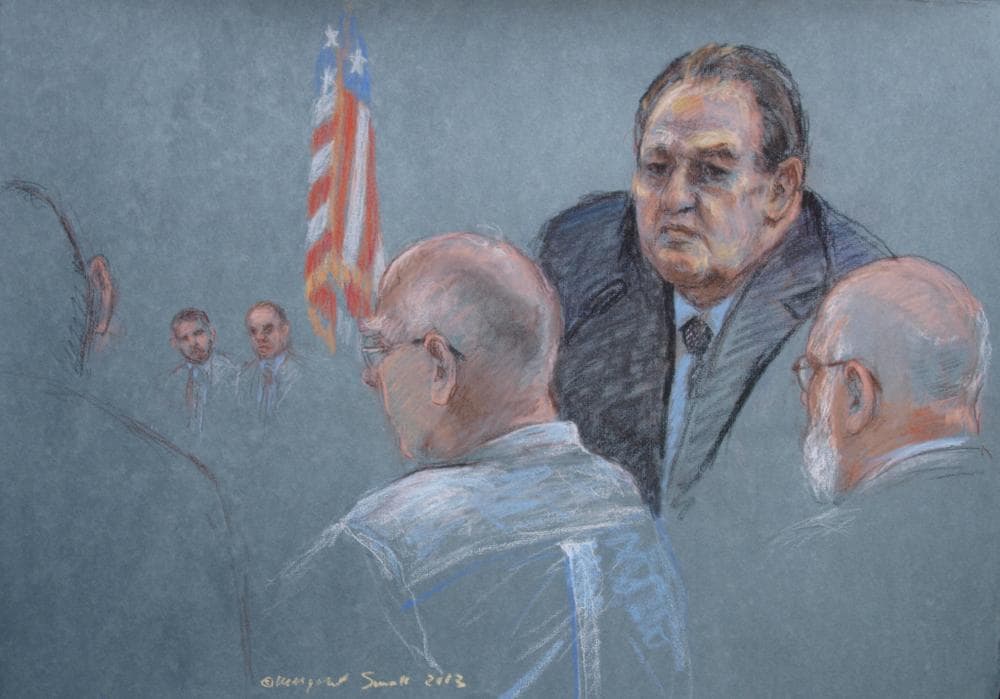

Why Justice Fell Short In The Trial Of 'Whitey' Bulger

In the minutes following Monday’s verdicts, the hall outside Courtroom 11 had the feel of a hospital trauma unit. Inside, federal prosecutors Fred Wyshak and Brian Kelly had racked up an overwhelming conviction of the vile and vicious James “Whitey” Bulger on 31 of 32 counts. But just outside, their statistical triumph was belied by the grief and shock of families who had just heard that the government had “not proved” Bulger’s role in the murder of their husbands, fathers and brothers.

Those 19 murders were at the heart of the government’s case, but the jury found the government had proved Bulger committed only 11 of them.

It was as if the prosecutors, the good guys, thought they couldn’t win if they exposed the full extent of corruption, collaboration, and willful blindness that had enabled a June bug to become a giant.

That scene in the hall will stay with me as long as I have a memory. Tears streamed down Connie Leonard’s face as she sought and embraced her twin sister, Brenna. Separated because the courtroom didn’t have enough room for both of them, they each endured the news alone that the government had failed to convince the jurors Bulger was criminally liable for the murder of their father, Francis “Buddy” Leonard, almost 40 years earlier. He had been shot 17 times. “I just don’t understand,” Connie said. Hugging me, she said it felt like her father had been shot 17 times again.

Walking through the stunned group, where even those who had gotten justice were quiet in their joy and compassionate for the grieving, Kelly walked up to Wyshak, who was standing next to me, and pronounced, “The jury didn’t like John Martorano’s testimony.”

As the gunman in most of the murders the jury didn’t pin on Bulger, Martorano had been the government’s main witness. He is a fat, mostly monosyllabic, and transparently unrepentant killer of 20 by his admission, and had gotten the most fabulous of deals, including an escape from facing the death penalty, freedom from prison after 12 years, and $20,000 walking money.

“Everything Martorano says is a lie,” one juror later quoted another juror saying during deliberations. If it is possible for a jury’s conviction of Bulger on 31 of 32 counts to seem somewhat hollow, here was the evidence. And here was the jury’s repudiation, in part, of “the government."

For Kelly and Wyshak it had to be bitter. They were the ones who had forged the indictment, in 1994, that caused Bulger to flee, and another indictment, in 1999, that finally brought Bulger to some justice. But to their great frustration, they kept getting tangled up in the widespread criticism of “the government” in this trial, as in “government corruption, government cover-up, and government misconduct.”

They saw themselves as the good guys. And for years, knowledgeable reporters and the team of state cops and one DEA agent who spearheaded the case against Bulger called them the good guys. The families of many of the victims had thought of them as the good guys, too.

But Wyshak and Kelly couldn’t exactly say “we’re not the government.” And the climate had changed and so had their tactics. Instead of distancing themselves further from the FBI and Justice Department, they had uncharacteristically defended the institutions or downplayed much that was indefensible.

The highest motive for bringing Bulger to trial was to give the families of Bulger’s 19 alleged murder victims an equal chance to see justice done. That brought them together, here at the trial. Yet together, the families posed a powerful indictment of the government's misconduct and indifference, which, while not nearly so violent and vicious as the defendant’s, had denied them justice and, in many cases, deprived victims of their lives.

In presenting their witnesses, Wyshak and Kelly showed a tendency to soften their image, to present them as men who decided to do the right thing. The families saw them the same way defense attorneys did: as calculated opportunists. And here, in an extraordinary turn of events, the likes of which I have never seen before and don’t imagine I will see again, the families of Bulger’s alleged victims started to cheer for the defense attorneys whenever they took to cross-examination.

“Mr. Martorano, you are a mass murderer, aren’t you?” asked attorney Hank Brennan in his opening question, quickly winning the respect and appreciation of the families.

Only in his closing argument did Wyshak acknowledge the struggle of conscience he and the prosecution faced before “the government held its nose and made the deal” with the contemptible Martorano. The rationale, he explained, was that if they hadn’t made the deal, so many murders would have remained unsolved.

In an extraordinary turn of events, the likes of which I have never seen before and don’t imagine I will see again, the families of Bulger’s alleged victims started to cheer for the defense attorneys whenever they took to cross-examination.

It was as if the prosecutors, the good guys, thought they couldn’t win if they exposed the full extent of corruption, collaboration, and willful blindness that had enabled a June bug to become a giant. But to fail to bring this out before the defense did only made it look like the prosecutors were hiding the truth. It alienated the families and, we now know, some of the jurors as well.

In his closing argument, Wyshak vented his full frustration, in an angry, sarcastic attack on the defense. Don’t let them turn your focus from Bulger, he told the jurors. "He’s the one on trial here, not the government, not the FBI,” or other witnesses. “They want you to believe how big bad government needs to learn a lesson in this case.”

Behind Wyshak, there were three rows of victims’ family members who believed just that. “A lot of people say the government wasn’t on trial here,” said Tommy Donahue, the son of murder victim Michael Donahue. In a louder voice, he pronounced, “Yes, they were.”

The irony of this trial is that in seemingly trying to defend the institutions, Wyshak and Kelly created more doubt among the jurors about the guilt of the killer they had fought so hard to prosecute. I won’t forget the image of Bulger smiling as he walked out of the court unburdened of eight murders. His thumbs were up.

Editor’s note: A longer version of this piece was originally published on WBUR’s Bulger on Trial site.

This program aired on August 16, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.