Advertisement

A Son Relives His Father's Tribulation At Writing 'Death Of A President'

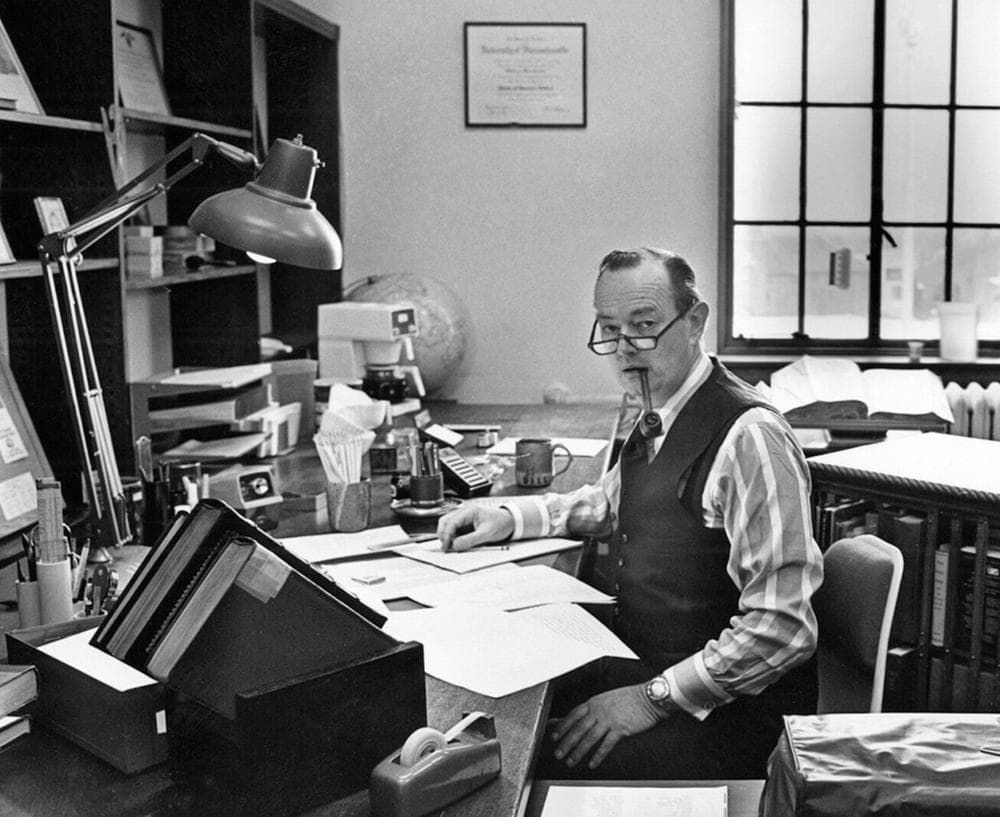

My father, William Manchester, wrote one of the definitive accounts of JFK’s assassination, “The Death of a President.”

Most Fridays in the fall of 1963 my father was working at American Education Publications, publishers of “My Weekly Reader.” I was typically in my eighth grade classroom.

But that Friday, November 22nd, my father picked me up early from school to drive me to a soccer game — the first and last game of mine he’d ever attend. Which was fine by me — I was as hopeless at team sports as he’d been as a kid.

I was strangely hopeful what had been missing all along in my game was my dad’s presence. That wasn’t the case. With him there I was worse than ever.

The world stopped. Someone stalked onto the field and announced, “The president has been shot.”

The world started again. Now I made no pretense of trying to connect with the ball, because I was blinded by tears. How could we still be playing this foolish game?

Finally, the game ended. My father didn’t say anything about our loss, or about the news. He just got in his car with a strangely apologetic expression, gave a little wave and drove off without me. I rode home sardined into the back of some mom’s station wagon. In that era before seat-belts, we usually took that opportunity to horse around. Not today. We didn’t make a sound, didn’t move. There was just that voice on the radio, and the faintest candle of hope. Sometime during that ride the voice snuffed it out:

“President John F. Kennedy died at approximately 1 p.m. Central Standard Time today, here in Dallas.”

The car dropped me at a friend’s, where I stayed for the next four days. I didn’t see my father until I got home. We never discussed it, but I can only think it was because he couldn’t bear for me to see him do what his father had forbade him to do: cry.

That March, Jackie Kennedy asked him to write the definitive account of her husband’s murder. He’d met John Kennedy on the Boston Common shortly after World War II, and counted him as a friend. He found the writing agonizing. Getting the book published was worse.

My father gave his all in the writing of “The Death of a President,” investing part of himself that he and my family never completely retrieved.

In the spring of 1966, Bobby and Jackie Kennedy decided they didn’t want him to publish the book and for nine months battled him in print and court to suppress it, as detailed in Vanity Fair, among other places, and in this essay by my father.

Finally on January 16, 1967 a settlement was reached allowing the book to be published. It was a bestseller. People would ask me, “What’s it like having a famous father?”

I’d answer, “I never think about it.” And I didn’t, because it was just too enormous. Until September of 1968.

I walked into my first class at Wesleyan University, English 101.

The professor introduced himself, and said, “We will start with a book by a great American author, William Manchester, a man whom I am privileged to call a friend. “The Death of a President.” And, I am pleased to have his son in our class!” He pointed at me. I blushed and slunk behind my desk. I didn’t hear another word he said, and when the bell rang I fled and never came back.

At the end of that semester I crept to the office of that professor. We were both in a bind. How was he going to explain to his good buddy Bill Manchester that he’d failed his son in English, of all subjects? Flunking English would put me on the fast track to Vietnam.

His proposed solution was that I read the book and write a long paper on it. With only hours left in the semester I read “The Death of a President” in one sitting — all 750 pages, wrote the paper, and escaped by the skin of my teeth. Despite the bizarre occasion, I thought the book was great.

Due to the terms of my father’s settlement with Jackie Kennedy, the book was long out of print. I am pleased that it’s finally available in a new paperback edition, and as an e-book, which I’m hoping will attract younger readers.

My father gave his all in the writing of “The Death of a President,” investing part of himself that he and my family never completely retrieved. That’s what lends the book such passion, and what makes it indispensable to understanding the wound that dark day in Dallas wrought on America.

A longer version of this essay appears at John Manchester's blog, Luminous Muse.

This program aired on November 22, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.