Advertisement

Secret 'Added Sugars' Threaten Your Health: Will Disclosure Help?

“Of the 600,000 items in the American grocery store, 77 percent of them have added sugar,” says Robert Lustig in a recent article published in the MIT Technology Review. “You can’t even reduce your consumption when you’re trying to.”

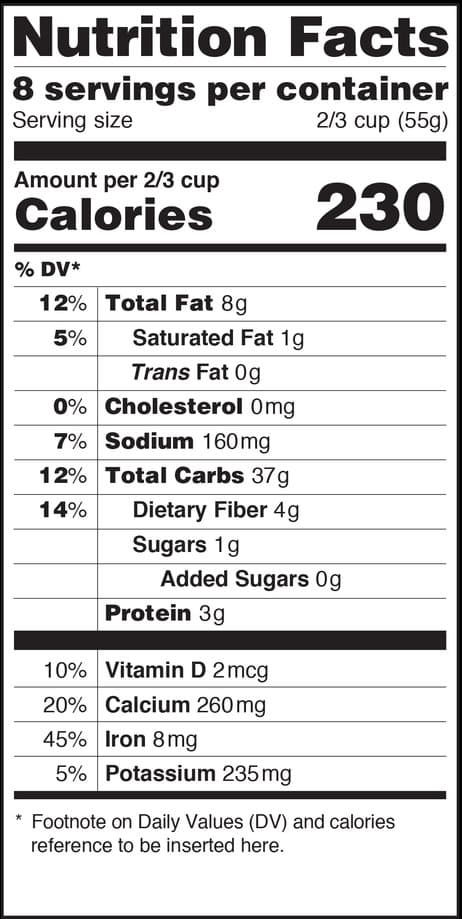

But proposed changes to the Nutrition Facts label on every package of food Americans buy may help. Among other things, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is adding a line for “Added Sugars.” The goal is to encourage Americans to eat less added sugar to lower obesity and improve health.

Disclosure has many naysayers. Mandated disclosures are seldom read, poorly understood and often misused. When the FDA first added a line for artificial “trans fat,” even the most at-risk consumers were likely to misinterpret the new disclosure, not knowing that just a few grams of trans fat was much more than anyone ought to eat.

Of the 600,000 items in the American grocery store, 77 percent of them have added sugar. You can’t even reduce your consumption when you’re trying to.

Robert Lustig

But the trans fat story is more complex than the label change alone, and convinces us that the added sugars disclosure holds promise.

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, artificial trans fat created through the partial hydrogenation of vegetable oils gradually replaced natural butter and other saturated fats in many packaged foods. At the time, trans fat was favored because it was cheaper, had a longer shelf life and seemed healthier than saturated fats.

By the 1990s, however, scientists had determined that trans fat has no health benefits. Instead, it clogs arteries, raises cholesterol and increases the risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. The Institute of Medicine recommended that people keep their trans fat intake as low as possible.

Although news stories about these developments alerted Americans that trans fat was undesirable, the average American in the mid-2000s was still eating nearly five grams of trans fat per day, in foods like French fries, microwave popcorn, chips and pastries.

Then, in 2006, the FDA put trans fat on the Nutrition Facts label. Soon thereafter, places like New York City banned the use of trans fat in restaurants.

True, many consumers did not read the trans fat disclosures, and at first, many of those who did misinterpreted them. But when companies started putting labels like “Zero Trans Fat!” on the front of packages, consumers got the idea.

Once Americans began choosing foods with no trans fat, companies had a strong incentive to get the trans fat out of their food. From McDonald’s fries to Crisco to Oreos, companies have found ways to substitute healthier oils while still maintaining taste, quality and shelf life.

By 2012, the average American ate only about a gram of artificial trans fat per day. Today, the FDA is working on a complete ban on artificial trans fat.

Added sugars may be at the beginning of a similar story.

Added sugars are strongly linked with obesity and chronic health problems. The American Heart Association recommends limiting daily added sugar intake to 100 calories for women and 150 calories for men. But Americans on average now consume 350 calories per day in added sugars, not only in soda and candy, but in everything from sandwich breads to spaghetti sauce. These sugars appear under dozens of names, including high-fructose corn syrup, dextrose, saccharose and fruit nectar.

Many added sugars can cause blood sugar to spike, which in turn contributes to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Scientists measure this by a food’s glycemic load. Glycemic loads of 10 or under, such as that of an apple (6), are considered low and healthy. Glycemic loads of 20 or more, found in a can of coke (25) or a plain bagel (36), are considered high and unhealthy.

Added sugars containing fructose are problematic in other ways. Our livers convert extra fructose into triglycerides, a type of fat. High triglyceride levels are a strong risk factor for heart disease and fatty liver disease.

But consumers do not need to understand glycemic load and triglycerides to scan the shelves and pick out which jar of peanut butter has “No Added Sugars!” emblazoned on the front. Although consumers are rightly skeptical of front-of-package “health” claims, putting added sugars on the Nutrition Facts label allows companies to credibly compete to provide healthier food.

New York City has already taken aim at added sugars, beginning with an attempted ban on large sugary sodas and an advertising campaign against sugary beverages. Lawsuits have argued that companies mislead consumers by disguising added sugars as “evaporated cane juice” and “concentrated fruit juice.”

Bans and lawsuits raise awareness, labeling educates consumers further and an added sugars disclosure on the Nutrition Facts label seals the deal.

If consumers start choosing foods with no added sugars, like they did for foods with no trans fat, companies will have an incentive to remove added sugars from their products. In a virtuous cycle, reformulated products give consumers more healthy options, and when consumers choose more of these foods, companies are further encouraged to reduce added sugars.

Will an added sugars disclosure stop Americans from eating sweets? No, and who wants to live in a world without ice cream and birthday cake, anyway? But do Americans want added sugars in everything from their fruit drinks and protein bars to their coleslaw and ketchup? The only way to find out is to give people the chance to make a choice.

This piece was co-authored by Marina Cassio, a second-year law student at Harvard Law School. Together, Willis and Cassio are conducting research on the use of disclosure as a regulatory tool.

Related: