Advertisement

What They Saw: The Liberation Of Majdanek 70 Years Ago Today

For over a month now, we have been marking and will continue to mark a procession of 70th anniversary milestones that originate in the final year of World War II in Europe. The Allied landings in Normandy, the liberation of Paris and, finally, the deaths of Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler as Allied forces began the assault and capture of Berlin.

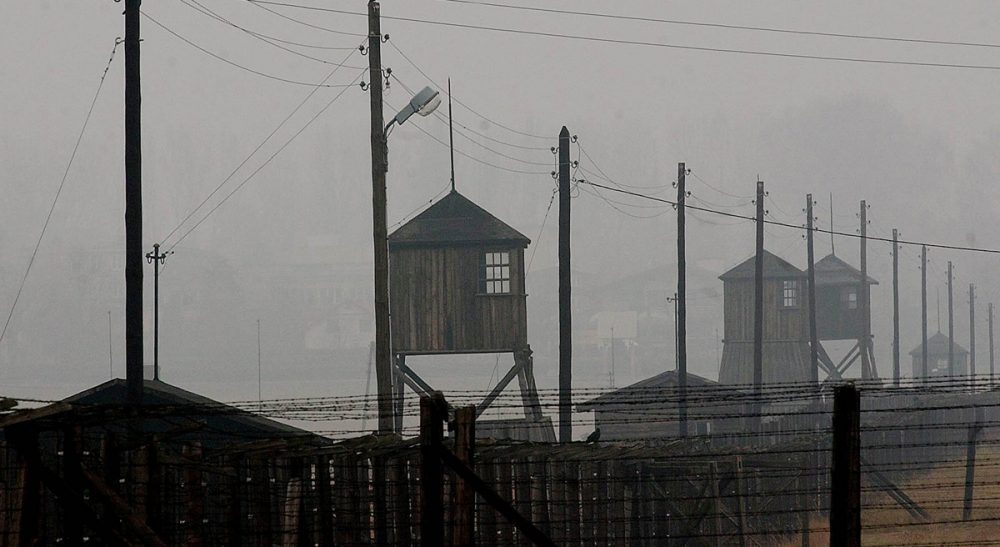

July 23 marks another of those milestones. Seventy years ago today, Red Army soldiers entered Lublin in eastern Poland and liberated the first Nazi death camp to be discovered by the Allies. Initially, the soldiers did not understand what they were finding. They had not been ordered to capture this particular site for any particular reason. But seeing the high walls and the large gate, they figured it was a sufficiently important enterprise to warrant inspection. The brick buildings, the smokestacks, the barracks — they all signified some kind of factory or industrial plant. But as the soldiers opened the doors to a gas chamber, an officer explained to them what they were about to see and how it operated. Not long after, they came across a crematorium that was still warm.

Initially, the soldiers did not understand what they were finding...The brick buildings, the smokestacks, the barracks -- they all signified some kind of factory or industrial plant.

It required many weeks before a disbelieving world came to grips with the news. The Soviet war correspondent, Konstanin Simonov, was flown into Lublin to write about the camp. His articles appeared in a long three-part series in Krasnaya zvezda (Red Star), the newspaper of the Red Army, and were the first to alert the world to its existence. Soon after, The New York Times dispatched its own correspondent, W. H. Lawrence, to Lublin so he could see the evidence for himself. His report, which ran on the front page on August 30, 1944, bore the headline, Nazi Mass Killing Laid Bare in Camp. It was the first such report to reach a broad American audience.

The articles by Simonov and Lawrence exemplified the problems that some correspondents experienced in understanding both the surface and the deeper significance of what they were seeing. Simonov made clear that he could only begin to outline the full scale of the horror he had witnessed.

“At some period in the future, after thorough and painstaking inquiry, the full immensity of the crime against humanity committed here by the Germans will come to light. I myself am at present in possession of only a fraction of the facts; I have spoken to perhaps only one-hundreth of the witnesses, and have seen maybe only one-tenth of the traces.”

But he still saw plenty. It was Simonov who was the first to describe a gas chamber and imagine the agony of the victims, to see canisters of Zyklon gas, to write about enormous piles of shoes that were overflowing warehouses on the grounds of the camp. “In one of the rooms of the camp offices, its floor literally carpeted with documents, identification papers and passports belonging to the victims,” he picked up papers at random that once belonged to a range of people, including children and the elderly. He also explicitly mentioned that “an immense number of Jews [were] brought to the camp to be exterminated from literally every country in Europe, from Poland to Holland.” In line with much, though not all, of Soviet treatment of what came to be called the Holocaust, the Jews as victims were listed along with Poles, Russians and others, as if the Nazis had not been targeting them uniquely for total annihilation.

Bill Lawrence's lead for the Times was grim and straightforward:

“I have just seen the most terrible place on the face of the earth — the German concentration camp at Maidanek, which was a veritable River Rouge for the production of death, in which it is estimated by Soviet and Polish authorities that at many as 1,500,000 persons from nearly every country in Europe were killed in the last three years.”

Scholars now believe that the number of victims at Majdanek was less than that, but still a staggering number in the low hundreds of thousands. Without verifiable records, it is only possible to give an estimate. Lawrence, as well, listed the Jews, along with “Poles, Russians, and…representatives of twenty-two nationalities” as the victims, as if he and his editors were still not ready to recognize that Jews had been singled out.

Related: