Advertisement

Do Clothes Maketh The Man?

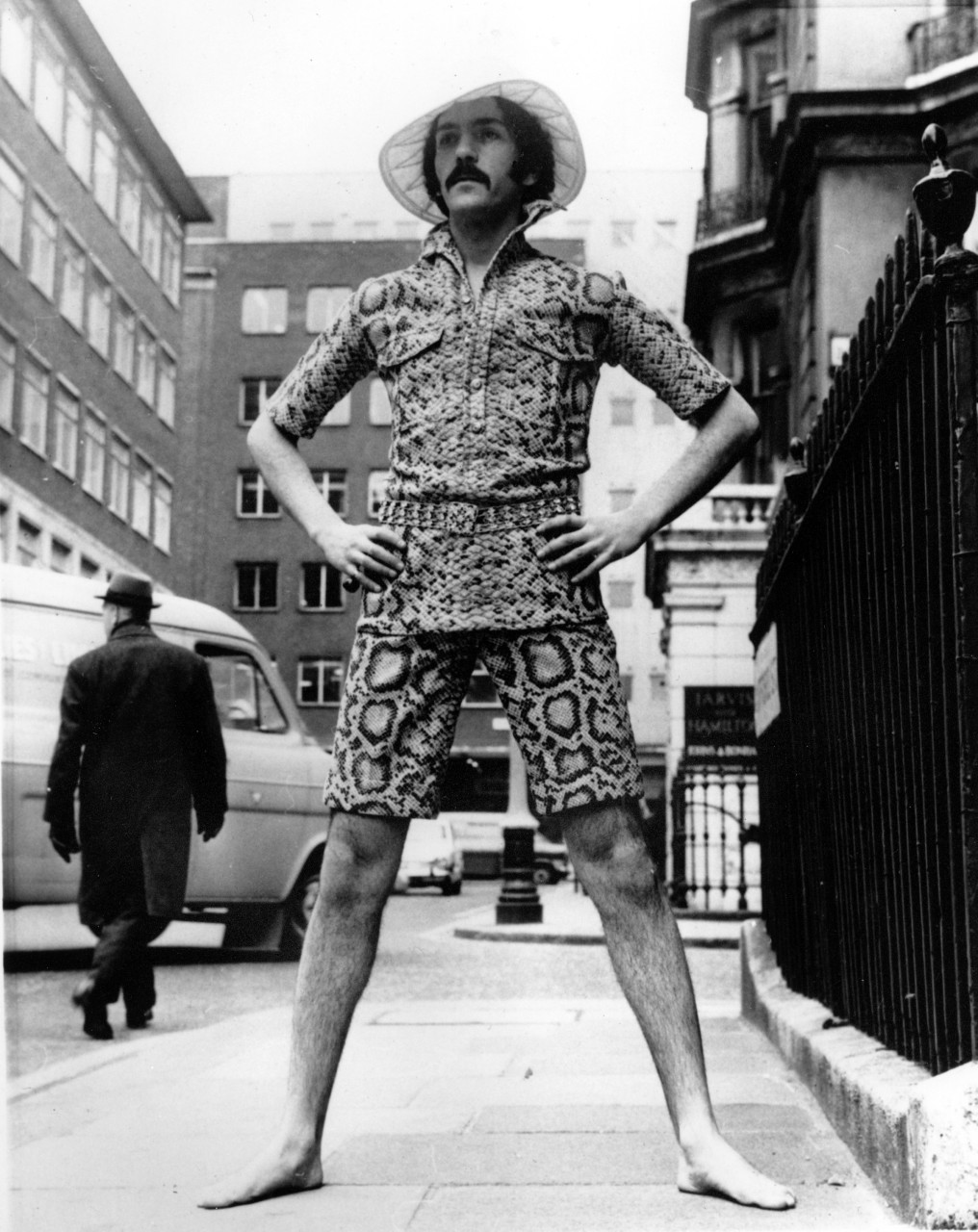

It recently occurred to me that I look terrible in clothes. Don’t get me wrong: I look worse out of them. But there is nothing I own that, on me, looks like it was meant to look. I am the black hole of fashion. Clothing designers look at me and immediately consider the virtues of a burqa for men.

My personal clothing goals are simple: cover the illegal parts, make me appear thinner, and don’t make me look like a tool. I admit it’s a tall order.

Clothing dates back 150,000 years or more. We don it for protection, ceremonial purposes, warmth and to make attractive people look at us and think, Hmmm, maybe after a few drinks... My personal clothing goals are simple: cover the illegal parts, make me appear thinner, and don’t make me look like a tool. I admit it’s a tall order.

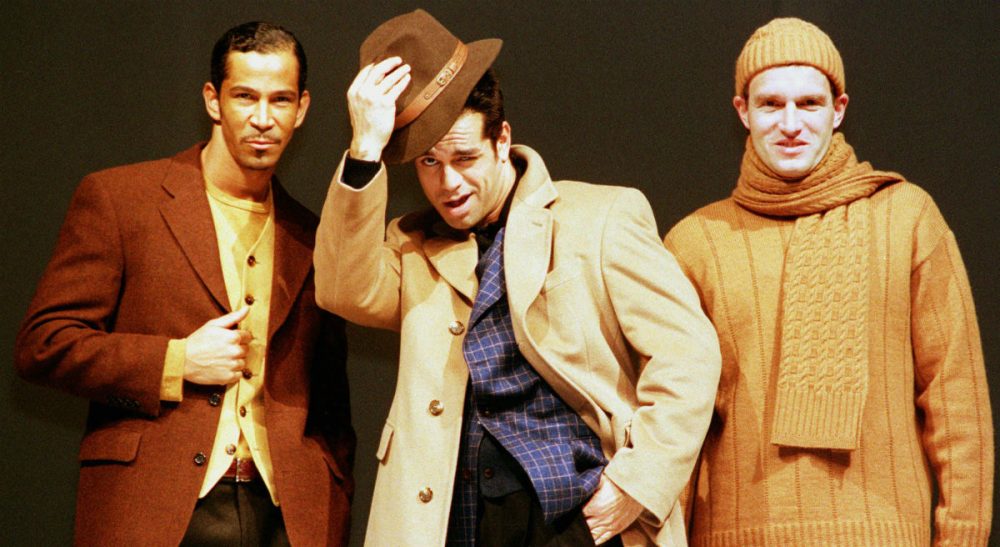

Most people, at least in part, dress to impress. It’s hard to overstate the importance of clothing when it comes to the perceptions of others. An article in Psychology Today cited a study of 300 people who were shown photos of men for three seconds each, some wearing tailored suits, some dressed off-the-rack. The study participants’ snap judgments reveal that most rated the men in the fitted suits as more confident and successful. In a similar study, women who dressed conservatively in the workplace were rated higher than comparatively “provocatively” dressed subjects.

Such psychofashion research doesn’t tell us anything we weren’t told by our guidance counselors long ago. But for me, it raises several questions: Are we really this superficial? What is the true value of first impressions? Would I rather deal with a well-dressed poseur or a person who eschews any form of artifice in the name of giving it to me straight?

I guess I don’t do enough psychologizing when it comes to dressing for the day. My wife does her best by laying out my work clothes for me. She knows all too well that, left to my own devices, I’ll indiscriminately match yellow with blue or red with green and brown, creating the overall effect of an Easter egg painted by a colorblind toddler. Things recently got easier when I expressed a desire to hide my slightly-larger-than-it-should-be gut. My wife suggested I start dressing in all black. “It’s thinning,” she said. I’ve taken her advice, and now all my friends are convinced I’ve joined a Johnny Cash tribute act.

Dr. Jennifer Baumgartner is a clinical psychologist and the author of “You are What You Wear: What Your Clothes Reveal About You.” Baumgartner considers the various meanings of our clothing choices and the corresponding effects on others and ourselves. Her take: Dressing is a behavior, and “any behavior is rooted in something deeper.” As markers of class and status, clothes, Dr. Baumgartner asserts, are also aspirational. “Our clothes help place us where we think we want to be.”

The way we dress also influences how we feel about ourselves, according to a Northwestern University study in which subjects were given lab coats to wear. Some were told it was a doctor’s coat; others a painter’s smock. The “doctors” performed the study’s assigned tasks in a more careful and attentive manner than the “painters” did. Dressing for success works two ways: It makes others and ourselves believe the best about us.

Things recently got easier when I expressed a desire to hide my slightly-larger-than-it-should-be gut. My wife suggested I start dressing in all black. “It’s thinning,” she said.

My own experience bears this out to some degree. When I was young and eager to climb the corporate ladder at a Fortune 500 company, I asked an acquaintance in the human resources department why my career had stalled. After suggesting I stop hanging with my ne’er-do-well friends from customer service during smoking breaks, he looked me up and down. A look came over his face that suggested he had just bitten into a rancid prune. But I could not deny what he was thinking: I put the emphasis in business causal on the second part of that phrase. “Wear ties,” he said. And so I did.

Nine months later, I was promoted to the international marketing department, where everything was great. There was just the boss and me, and we made a great team. Finally, I could relax my sartorial standards, for the boss himself dressed more like a caddy than an executive. I put my neck wear away.

About nine months into my new gig, however, I noticed that my boss started wearing ties. He was soon gone, and I was left to man the department alone, working 60 hours a week, struggling to fill his shoes. I thought maybe it was time to get the ties back out. Then I changed my mind and decided perhaps I needed a career where untucked shirts, badly sized pants and embarrassing stains were the norm.

I went to work at a newspaper.

Related: