Advertisement

What’s The Harm? On Having A Drink Then, And Now

Not much has changed in the world of booze and young people over the centuries. In the fall that I helped my daughter move into her room at college, I noticed a young man in the driveway of the house next door wrestling an empty beer keg onto the back seat of his car. As so often happens whenever I visit a college campus, I recalled my own youthful struggles with alcohol.

I grew up in a town where alcohol was like oxygen: ubiquitous and taken for granted. Every day’s cocktail 'hour' pushed dinner later and later. On weekends, Bloody Marys preceded lunch.

I grew up in a town where alcohol was like oxygen: ubiquitous and taken for granted. Every day’s cocktail “hour” pushed dinner later and later. On weekends, Bloody Marys preceded lunch. My parents and their boisterous friends seemed always to be picnicking in fields or on the beach or outside stadiums, waiting for the start of football games. Many of these gatherings included us kids, swept along on a wave of hilarity and excitement, enjoying the camaraderie of the grown-ups and the attention of fathers who, most of the time, disappeared into offices and on business trips. The picnics always included flasks and coolers filled with ice and lemons and Schweppes and Mr. and Mrs. T.

Because it seemed to strike our fathers as cute and funny to give toddlers a sip of beer or gin and watch them grimace, I imagine I had tasted liquor well before the first beer party the adults actually threw for us. But that party was the first time I had ever been drunk. I was thirteen. At some point in the evening, I stumbled outside and fell down an embankment, badly spraining my ankle.

A few months later, in the fall of 1956, I went off to a boarding school in the woods of New England, where the only alcohol was the optimistic fumes of our attempts to create hard cider. That is, until we cultivated the right teachers. Then we drank their liquor. I drank scotch starting at seven in the morning of my senior-year SAT exam. By half-past-eight, when the exam started, I was drunk and in a festive mood, which must have helped, because my score rose 100 points from my first attempt. One Tuesday night before Ash Wednesday, I drank vodka in the parish house of a minister friend of one of my teachers. We burned palm leaves in a sink.

I was well prepared for college. Freshman year began with rush week, a parade of besotted parties thrown by fraternities and sororities looking for a new crop of drinking buddies. The drinking never stopped. We drank during football and basketball games, between classes and all night. Though the college had a nominal rule against drinking in the dormitories, I attended an annual cocktail party given by a grad student in an adjoining suite; the dean of the School of Arts and Sciences was there, too.

This was my world, and it all felt fine — reasonable and normal and great fun, except, perhaps, for the hangovers. These were brutal, grinding bouts of vomiting and headaches. I lay in bed moaning and vowing never to drink again, but a couple of morning screwdrivers fixed me right up. This cycle of euphoria and pain became the pattern of my life, and I followed it blithely into adulthood.

I floated merrily down a river of booze, hosting house parties that went on for weeks with dozens of friends. We had parties at a beach house, on boats, in the mountains of Vermont, at Saratoga race track — Irish coffee, Champagne, vodka, wine, beer. My wedding was just another big party. I had a child, and we took her to parties at restaurants, where she slept under the table, lulled by laughter and raucous fellowship.

In the schools where I taught, recovering alcoholics in special assemblies warned students about the dangers of drinking. They had little effect. Part of the problem was that these former drinkers seemed fine. Despite the stories they told, they had survived and appeared to be doing well. And their stories made their lives seem like good, outrageous fun. The students laughed knowingly, recalling or anticipating their own exploits. That the speakers had quit drinking after the parties, after they had had their fun seemed just to reinforce the mythology of most young drunks: They could stop anytime they wanted.

I lay in bed moaning and vowing never to drink again, but a couple of morning screwdrivers fixed me right up. This cycle of euphoria and pain became the pattern of my life, and I followed it blithely into adulthood.

Some know that drinking-and-driving is stupid and dangerous. The twisted wreckage towed to the front lawn of the school a few days before the prom, the tearful stories from other teen drivers who lost or even killed friends, appear to penetrate the haze of immortality that surrounds youth. And adults are often serious about collecting car keys.

But all the other adult messages about alcohol remain the same as when I was a boy. Adults continue to throw parties, to drink with the young, to chuckle over the cuteness of a two-year-old taking his first sip, to reinforce the iron connection between booze and fun. They’re only young once, the thinking seems to go. What’s the harm?

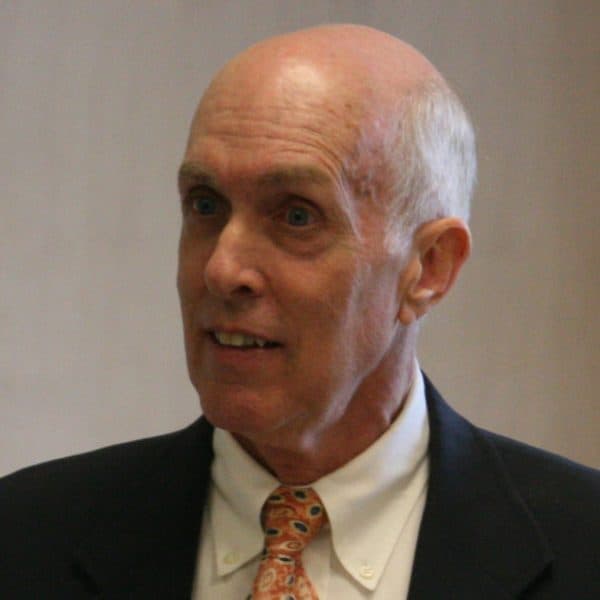

The harm is invisible. The young fellow slamming his car door on the empty keg looks at me but doesn’t see the wreckage standing right in front of him. He doesn’t see the scarred ankle that finally had to be rebuilt. He doesn’t sense the sadness of lost friendships drowned in alcohol or feel the depression and rage. He can’t see the brain lesions that diminish intelligence or destroy memory. He can’t see the bleeding ulcer, the failed marriage, or the trail of destruction behind me. He just looks at me with a big goofy grin.

Related: