Advertisement

Atlantic Cod And The Human 'Tragedy Of The Commons'

He never got a high school diploma. He didn’t need one, with his dad taking him out on the side trawler to the rich Georges Bank fishing grounds off New England. Helping out on the boat earned Tony good money. Real good money. Cod money.

The nets would come up so full back then — in the 1970s — they’d tip the gunwales down almost to the water line. The fish would flop on the deck so deep they were up to his hips. He had to wade in them, wade in the money. Why go to school when two months of summer work could bring in as much as $100,000 for the 16-year-old son of an immigrant fisherman who would grow up and inherit his dad’s boat and all its earning potential.

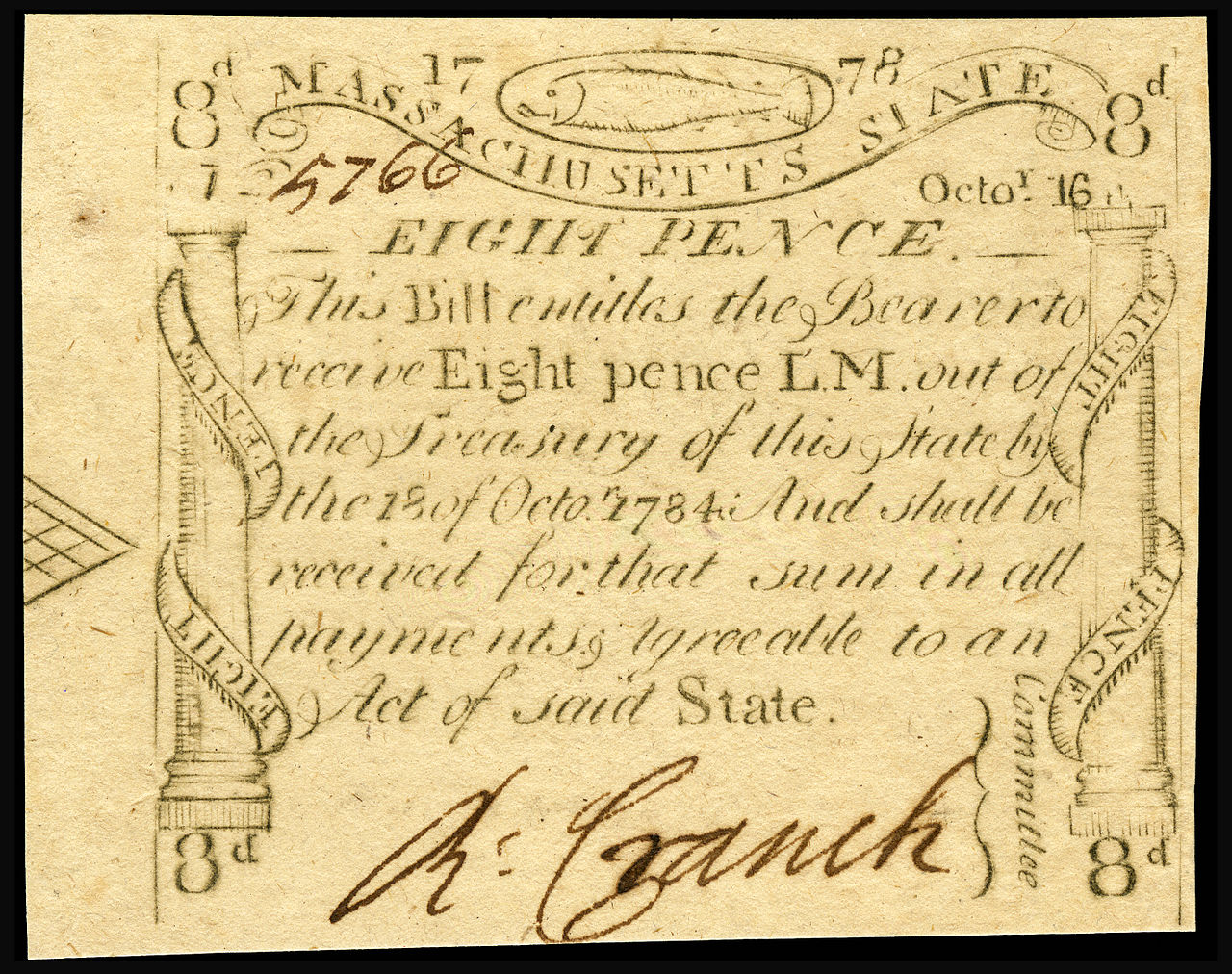

The cod off Canada and New England are essentially gone now. Stocks have been so depleted that marine biologists doubt they can ever recover. Cod fishing in the Gulf of Maine has now been banned by federal fisheries managers in a desperate last minute attempt to save a species that was once so plentiful that, as far back as 1,000 years ago, it drew Vikings and Basques and thousands of Europeans across the Atlantic to make their living. Cape Cod was so named in 1602, 18 years before the pilgrims came ashore in Plymouth. (By the way, they chose that destination because of the plentiful cod.) The rich cod fish trade — “they’re so thick by the shore that we hardly have been able to row a boat through them,” reported one captain — helped give birth to Boston and to America. The first wealthy merchants in New England were called the “codfish aristocracy", and the Sacred Cod was first hung in the Massachusetts Legislature in the 1730s. The cod was the symbol on the state’s early money. Not God. Cod.

But the decimation of the cod fishery off North America goes way back too. As early as 1693, the Massachusetts legislature tried to minimize overfishing by ordering farmers to stop using cod as fertilizer. To little effect. For the next 300 years more and more boats with better and better technology vacuumed cod from Georges Bank and the broader Grand Banks that flank Canada up to Newfoundland. The Atlantic cod is an incredibly robust and fecund fish, but predictably, it couldn’t stand up to intense pressure from a fleet of factory fishing trawlers armed with GPS-directed fish finding sonar.

And just as predictably, fishermen and business interests fought conservation efforts, denying scientific evidence that they were harvesting away their own futures. The Newfoundland fishery collapsed and was closed by the Canadian government in the 1990s. The New England Fisheries Management Council has been the slowest of America’s eight councils to limit overfishing of a vital species. Finally, the federal government has stepped in, banning all cod fishing by net or trawling, including recreational, for at least the next six months.

The hope is that the population of the Gulf of Maine cod, reduced to as little as 1 percent of what it once was, can “recover.” The Newfoundland fishery has been closed for nearly 30 years, but there are only the faintest glimmers that the population is recovering. Other species appear to have taken over the marine ecosystem.

Tony’s father Francesco came from Sicily in the early 1900s when the cod were thick and the money poured in. He gave his family the Great American Life, and left his 90 foot stern trawler, “The Frankie C,” to his son. Tony started taking his son, Francesco Jr., out on fishing trips when the boy was 12 to teach him the family business on the boat that might one day be his. Frankie Jr. loved it; steering the boat, sorting and gutting the fish, learning to be a fisherman like his dad.

Fishing fed Tony’s family well -- for a while. But starting in the 1980s, every time the net would come back up, there were fewer and fewer fish.

Fishing fed Tony’s family well — for a while. But starting in the 1980s, every time the net would come back up, there were fewer and fewer fish. Government restrictions cut into how many days he could fish, and where. Finally there weren’t enough fish coming up to pay for the fuel and ice and crew. Tony sold his boat to investors who took "The Frankie C" out to the west coast.

Tony bought a little fish and chips place in town. But he was depressed. His pride was gone. His sense of self was gone. The profits he had put in the bank were all but gone. He found comfort the way a lot of out-of-work fisherman in New England did. Tony died of a heroin overdose a few years ago.

In 1968, economist Garrett Hardin published a short essay called “The Tragedy of the Commons.” A modern take on Malthus (the British scholar who in 1798 predicted doom if population growth continued to outpace the growth in food production), Hardin proposed that in a growing population, if everybody takes as much as they want from a finite pool of resources, the pool will run dry. Examples of "The Tragedy of the Commons" are everywhere in our crowded world. New England and Canadian cod are one. So is Tony.

Editor's note: David Ropeik spent five days fishing on Georges Bank with “Tony” and "Frankie Jr." aboard "The Frankie C” in the early 90s. The facts in this piece are true — but the names have been changed, out of respect.

Related:

- Cognoscenti: This Thanksgiving, I’m Thankful For The Atlantic Cod

- Here & Now: Atlantic Fishermen Grapple With Cod Restrictions

- Radio Boston: Fisherman Protest Cod Fishing Restrictions In Gulf Of Maine