Advertisement

I Was Juror 359, But I Wasn’t Seated On The Tsarnaev Jury

For the past three months, my life has revolved around Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

I’m one of more than 1,300 people who made up the jury pool for his trial at the federal courthouse in Boston.

This was the process:

My summons came on the Monday after Thanksgiving. December was spent notifying family and my employer. Articles about the selection process gave us a hint of what was to come, but I had no idea what to actually expect.

Everyone else in my life, it seemed, had ideas — and opinions:

“Say you want to fry him.”

I couldn't lie -- even though the truth might get me seated. Don’t we want the victims to have a chance for justice? Don’t we want the court to get it right? There’s a societal responsibility that comes with this conscripted territory.

“Say you’re against the death penalty.”

“I’d LOVE to sit on that jury.”

“Go there decked out in 'Boston Strong' gear.”

“Are you lying for attention? This can’t be real.”

It was never-ending. My jury pool status has been an exercise in imagination, a source of entertainment and three months of “Law & Order”–like legal speculation.

For my husband and me it’s been non-stop anxiety. How will we manage if I get seated? How long will it take? How much notice would I get? How would the selection process affect my spring classes? What would my husband and I do about childcare?

When Jan. 5 arrived — the day I filled out my survey — I was relieved.

I sat in the second row of the jury assembly room at the courthouse, looking at the brilliant blue sky and the sun sparkling on the harbor — and the cadre of press representatives tweeting and tapping away on the other side of the window, staring at us, sizing us up.

Let’s get this over with, I thought.

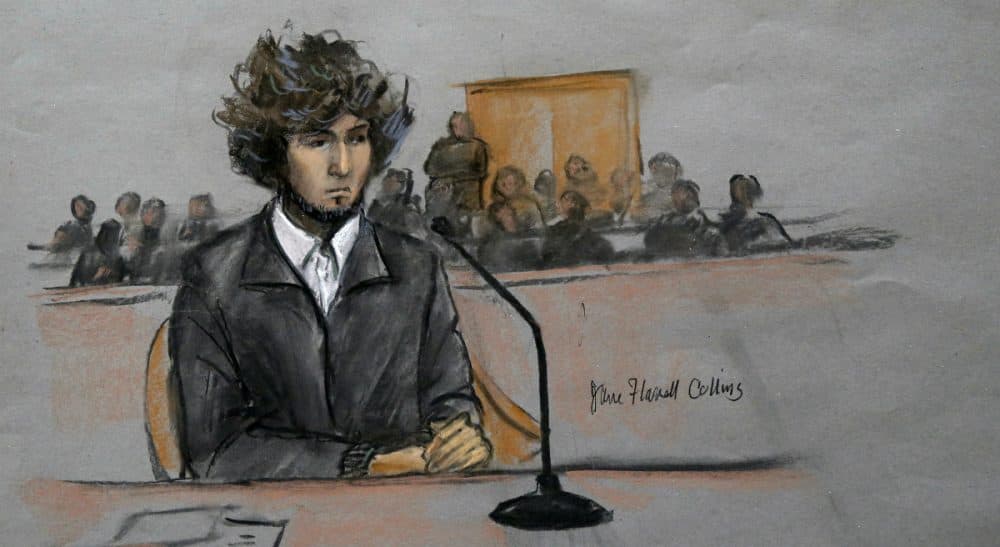

When Judge George O’Toole came in, followed by the prosecution and the defense teams, the air in the room changed. Tsarnaev was there — none of us had expected that — and he sat 10 feet in front of me, all slouched posture and patchy facial hair in a gray sweater. His eyes — one of which is more deeply hooded than the other, perhaps from his injuries — slid from the table, over us, to the table. Over to me.

There was no cloud of evil that floated around him, nothing that marked him as being different from one of my doofy sophomores... except every single person was there because of what he'd done.

His presence did, however, bring gravitas to the room. His defense team studied our faces. At one point, I locked eyes with attorney Timothy Watkins. Somewhere in the crowd were the people who would determine whether Tsarnaev would live or die.

Maybe me.

Judge O’Toole gave us clear instructions for answering questions, and Jim McAlear, the jury commissioner, followed up to make sure we understood. Tsarnaev filed out, bookended by his team, and we got to work.

The survey was 23 pages long. There were 100 questions. It took me nearly two hours to fill it out. I detailed my feelings on the death penalty, the media, which news sources I use. I was thoughtful and careful.

I disclosed the essay I had written about the bombings on my blog. I disclosed that I wrote about the Gardner art heist in my 2013 novel for kids. I listed all of my books.

Before I left, I was told to call back the following Monday.

And this began three weeks of calling the jury hotline twice a week. I’d call Monday and be instructed to call back on Wednesday or Thursday. Had they started bringing people in? When would that happen? I wasn’t allowed to know. Would I have to cancel class this week? Next week? Could I keep my dentist appointment?

“He’s guilty. Tell the judge.”

“Cry a lot. Can you cry?”

“Be angry. Tell them you know someone who ran.”

“Lie.”

There was no cloud of evil that floated around him, nothing that marked him as being different from one of my doofy sophomores... except every single person was there because of what he'd done.

I found myself having to defend the agonizing selection process. I couldn't lie -- even though the truth might get me seated. Don’t we want the victims to have a chance for justice? Don’t we want the court to get it right? There’s a societal responsibility that comes with this conscripted territory.

One night, a friend wondered if the trial teams had read my essay. I checked site stats by location. There it was:

Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

It’s one thing to think that Big Brother is watching you; it’s another to know it.

And then the message changed. I called on a Thursday and was instructed to call back Friday. Then Monday. Tuesday. Wednesday. Thursday.

“You are now instructed to report to the Federal Courthouse on Friday, at 8 a.m.”

Voir dire. I had 14 hours notice. A late evening scramble to find childcare ensued.

In between the second and third blizzards of the year, on the first sub-zero day that the T failed, I schlepped into town.

I was sworn in with 18 others, Tsarnaev and both legal teams present. Watkins and another attorney, Judy Clarke, watched us closely. They had our surveys. Did they recognize me from their online research? I thought they did. Tsarnaev seemed unconcerned with our group, glancing over at us occasionally, but eyes mostly on his hands.

We headed to the jury room.

One by one, prospective jurors were taken before the judge and teams. No one was allowed to return after being questioned — you had to take your belongings with you — and we couldn’t leave. Lunch was brought in.

We weren’t permitted to talk about the case, but we talked about other stuff: MCAS and school testing, movies and TV. How boring the jury room was. We asked for a deck of cards. We were told to be quiet; we were laughing too loudly. By 4:15 p.m., the court day was winding down and I was one of three people left. My number came up, and I was escorted past the courtroom.

“Wait. Aren’t I supposed to talk to the judge?”

The jury assistant shook her head. “No. Sometimes that’s the process.”

I spent two months worrying about this, revolving my life around this, and didn’t get to talk to the judge. According to tweets from local journalists, it was because of my “social media posts” — probably that essay, as I haven’t posted anything about being in the pool (I was instructed not to). And perhaps because it was 4:15 p.m. on a Friday and everyone wanted to go home.

Before next juror, they discuss some of her social media posts. They decide not to bring her in. #Tsarnaev— Gail Waterhouse (@gailwaterhouse) February 6, 2015

Another juror, a woman, was just disqualified before being brought out, Today's pool drops to 17.#Tsarnaev— Laurel J. Sweet (@Laurel_Sweet) February 6, 2015

Sometimes that’s the process.

I called the hotline biweekly as instructed all through February, knowing that I wouldn’t get excused until the jury was seated. However, my juror message alarmingly changed to “You are now a potential juror in Judge George O’Toole’s courtroom.” But I guess anyone who was brought in for voir dire got that message — even if you didn’t see the judge.

This week, when they finally seated the jury, I found out I’d been excused. I’m now free to talk about my experience and follow the case. To book flights and keep my dentist appointments. But I empathize with every person selected. No matter what they decide, there’s a group out there who will vilify them for their decision.

There’s been a lot written about the pool; a lot of glib remarks about “idiots” and people “skipping” out of the courtroom. But these are your neighbors. Your friends. Your coworkers. No one has asked to be there. No one volunteered. No one is an “idiot.” These people are more than what you see on a survey or in a soundbite. To reduce them to two-dimensional cutouts is naïve and does all of us a disservice. Instead, thank them for putting their lives on hold. Thank them for doing their best to get it right. For participating in the process.

And wish them luck, logic and strength for what they will see and the burden they will carry.