Advertisement

Attracting Latina Students To STEM Careers, One Role Model At A Time

I remember the day I told my parents I was pregnant. It was 1997, the fall of my junior year of high school. We had immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico a little over a decade earlier. We — my parents, my siblings and I (plus some extended family) — lived in a cramped two-bedroom apartment outside of Los Angeles. My parents worked at a bungee cord factory.

When I broke the news, my mother, who has a second grade education, wept. “I thought you wanted to go college,” my father said softly. “What about your education?”

When I broke the news [of my pregnancy], my mother, who has a second grade education, wept. 'I thought you wanted to go college,' my father said softly. 'What about your education?'

All along, college had been my plan. I took many AP courses, was ranked second in a class of more than 700, and my SAT scores were high. At that moment, though, college seemed a distant dream.

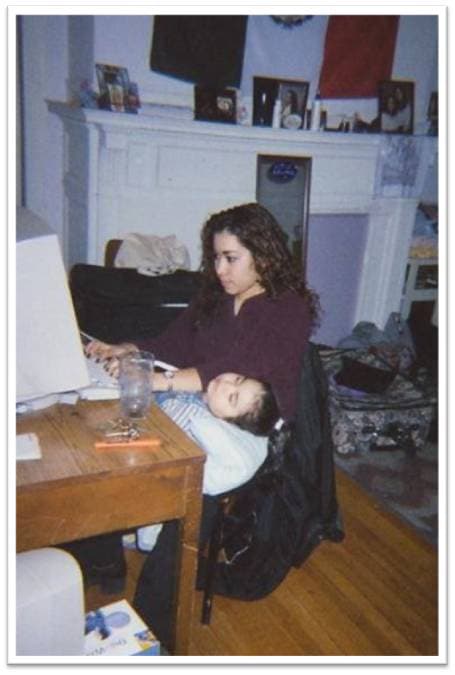

A few months later, an alumnus of my high school named Jesus Perez visited my class. He was a senior at MIT. His father was a janitor and his mother was illiterate. He told me about his experience at MIT and the power of an engineering degree. He encouraged me to apply. I got in, and, two years later, my year-old daughter and I boarded a plane for Boston.

Today, my daughter is 16 years old, and I have three degrees from MIT. In my work as an engineer and technical leader at Boeing, I drive improvements in the company’s product development programs.

I love my job in aerospace, but every time I sit in a meeting and realize that I’m the only Latina, I wonder why. Although research shows that jobs in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) are increasing, the number of Latinas pursuing degrees in these fields is slight. While women account for 24 percent of the STEM workforce, Latinas represent only 3 percent. What’s more, studies and anecdotal evidence show that women — particularly women of color — who pursue STEM educations and careers, face gender and racial biases in the classroom and the workplace. This accounts, in part, for their higher propensity to leave the field.

What will be the tipping point for Latinas in STEM? It starts with family. I was lucky that my family was so supportive. Not all parents are. It’s critical to reach parents of young Latinas and address the pervasive cultural resistance to allowing daughters to move away from home and go to college. The message has to underscore the opportunity parents have to help their daughters grow up to become self-sustaining women.

Relatable role models are also important. Mine was Jesus Perez, who graduated from MIT in 1999 and earned a master’s degree from Stanford. When he encouraged me to apply to MIT, his words were a revelation. Here was a successful person who looked like me, who sounded like me, and who truly understood my life experience, telling me I had what it took to go to MIT. We must reach Latinas with this message even earlier, in after-school and summer programs and through outreach in K-12 classrooms and career days.

Parents need role models, too. If parents don’t know scientists, engineers or mathematicians from their community, it’s difficult for them to encourage their daughters to envision a future in those fields. It’s up to those of us working in STEM to shed light on opportunities and share our stories, so that these careers become tangible to parents.

Mentorship and networking opportunities are the third piece of the puzzle. Every Latina needs someone powerful in her corner. The summer before I started college, the Los Angeles Times published an article about me: "Teen Mom Is a Standout, Not a Dropout." The story caught the attention of Claire Leon, then a manager at Boeing. She called my high school and offered me an opportunity to interview for an internship at the company. That internship opened my eyes to the possibility of a career in engineering. Claire and I have remained close, and, throughout my career, she’s given me advice and support.

My daughter, who literally grew up on the MIT campus, is now a junior in high school. She’s had the privilege of exposure to various careers and universities, and, although she’s not interested in engineering, I’m thrilled she knows she has many options. Let’s extend that privilege to all young Latinas.