Advertisement

Patrick Kennedy, And The Politics Of Memory And Truth

When I learned earlier this week that Patrick Kennedy wrote a memoir, my first thought was hurrah for the kid! Not that he is such a kid: at age 48, with a wife and two little children and a career that includes having served in Congress as well as a personal history of struggling with alcohol and drug abuse, we are talking about someone with enough life experience to have something worth saying, someone old enough to bring the memoirist’s most essential tool, hindsight, to the enterprise.

Still and all, as a memoir writer, Patrick Kennedy faced an especially daunting prospect.

All families mythologize themselves, but the Kennedys tend to mythologize themselves in boldface and in italics. Patrick Kennedy’s branch included his father Ted, his older brother Edward, a sister, Kara, his mother, Joan, and later his stepmother Vicki. His uncle John was president and his uncle Bobby ran for the same office: both were assassinated, leaving baby brother Ted to carry the family banner.

All families mythologize themselves, but the Kennedys tend to mythologize themselves in boldface and in italics.

It also doesn’t help in the memoir biz to come from an Irish Catholic background. In my family, we had scripted answers drummed into us by our mother, for questions from “outsiders” (pretty much anyone who did not emanate from her womb) for what she called “personal questions” (pretty much everything but the weather).

“If anyone asks,” my mother would say, whether talking about my older brother dropping out of high school and his struggles with mental illness, about the family’s financial predicament (all in the direction of subtraction), or our closeted gay uncle, “Just say…” and then the rote words.

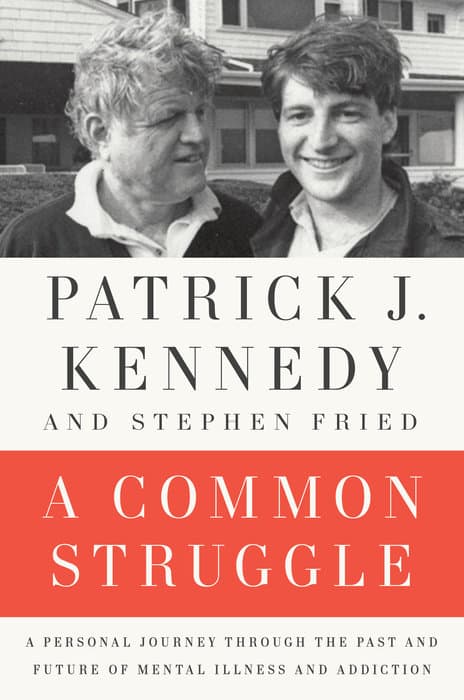

In his column in the Boston Globe about this new book, which is titled “A Common Struggle: A Personal Journey Through the Past and Future of Mental Illness and Addiction,” Kevin Cullen quotes Seamus Heaney on this genetic tic: “Whatever you say, say nothing.”

I suspect the Kennedys had their own version of canned answers to vexing questions, only theirs got printed in every newspaper in America and then some.

I teach memoir and I always tell my students that to people who have never written a memoir, they can perhaps appear slight: carry-on luggage versus a steamer truck. Yet we generally reserve for our carry-ons the things we think we think we cannot live without, so there is a strict, if unspoken, system of triage at work in memoir, a radical economy. Memoirs are about essentials. They go to the heart of the matter with headlong intensity. Novels, intrinsically more discursive, often take the scenic route.

The very word, memoir, has a dainty, precious, scented sound, like boudoir or bon bon, and that there is something admirable and old-fashioned about the often slow-paced methodical explorations practiced by writers of memoir. Most memoirs are about events that occurred in dusky venues long ago and would be doomed to remain obscure but for the author’s perverse insistence to the contrary (for instance, Patrick Kennedy and his siblings trying to do an intervention with their father after an Easter weekend bender boozing with his nephew, later accused of rape).

Do not kid yourself.

There is nothing about a good memoir that is soft or easy.

It is not a genre for the faint of heart.

First of all, the very material that makes its way into memoir is often heartbreaking, requiring ruthless self-scrutiny. Just because writing is a quiet act that involves sitting still for long stretches does not make it any less of a blood sport. With memoir the sword slashes in two directions. Not only is the work being reviewed, but also the quality of the life led by the writer. Patrick Kennedy, take note: if skin is biologically capable of generating its own extra layer, this would be an ideal time.

I want to tell him, gently but firmly, to keep in mind that the very people he is writing about are likely to be the least supportive.

His own brother, Ted Jr., has said he is heartbroken about the book: “My brother’s recollections of family events and particularly our parents are quite different from my own.”

Well, of course. We are all an island unto ourselves, et cetera, even in our family of origin — especially in our family of origin.

When Carole O’Malley Gaunt wrote “Hungry Hill,” whose title comes from the Irish-Catholic neighborhood in Springfield, Massachusetts, where she grew up during the 1950s and 60s as the only girl with seven brothers, she expected some objections from at least some of her siblings, and she got them. (Her book documents a childhood with a series of “before and afters.” First, there is the death of her mother by cancer and less than three years later, the death of her father due to complications from alcoholism. The catalogue of indignities that follows has a Dickensian quality that might seem exaggerated if it also did not seem true and if the account were not leavened with humor.) When one of the author’s brothers took issue with her book, and suggested she could have also folded in more of the good times, she said, “You write the joyful version. I am sticking with what I remember.”

You write the joyful version. I am sticking with what I remember.

In the end, the point of the writing is the writing and there is no dishonor in that, but there may not be any deliverance either.

I also want to reach out to Patrick Kennedy, to make sure he knows that writing a memoir is no cure-all: a bittersweet sense of the doomed nature of the enterprise will permeate your effort. Above all I would urge him to keep in check any fantasies that because he has recreated the past he has repaired it. You cannot resurrect the dead, nor can you erase ancient injustices, nor does sorrow flee simply because it has been confronted. In the end, the point of the writing is the writing and there is no dishonor in that, but there may not be any deliverance either.

In 1996, when James Carroll’s “An American Requiem: God, My Father and the War That Came Between Us” was published, he made the same point in an interview in Publishers Weekly, and this was after he had won the National Book Award:

I had this fantasy when I was writing “An American Requiem” that by the end of it I was going to feel fine. I kept thinking that I would have worked through all this stuff, and there would be a knot I would tie, and I’d be able to put down my pen and say, “Thanks be to God.” This has been a great experience. But it shocked me to get to the end and just feel completely, to use my father’s word, heartbroken. It’s very confusing to me, really, because it is a very sad story.

The single most powerful motive I have in telling this story is that my children can have it. One day, when I watched my children shrink back in fear from my father, who was by that time in the grip of Alzheimer’s, I was so overwhelmed with sadness because I knew they would never have a memory of him when he was great. I want them to understand who he was, who my mother was, and what we’ve been through together.

Finally, to Patrick Kennedy I want to say congratulations. I have a friend, Jay Neugeborn, who wrote about his brother’s mental illness in a book called “Imagining Robert,” certain that his mother would not approve. She surprised him, signing a release, and even giving him her blessing. "This is a story everyone should know," she said.

A story everyone should know: the perfect benediction as you set forth.

Madeleine Blais is the author of the 2002 memoir, "Uphill Walkers."