Advertisement

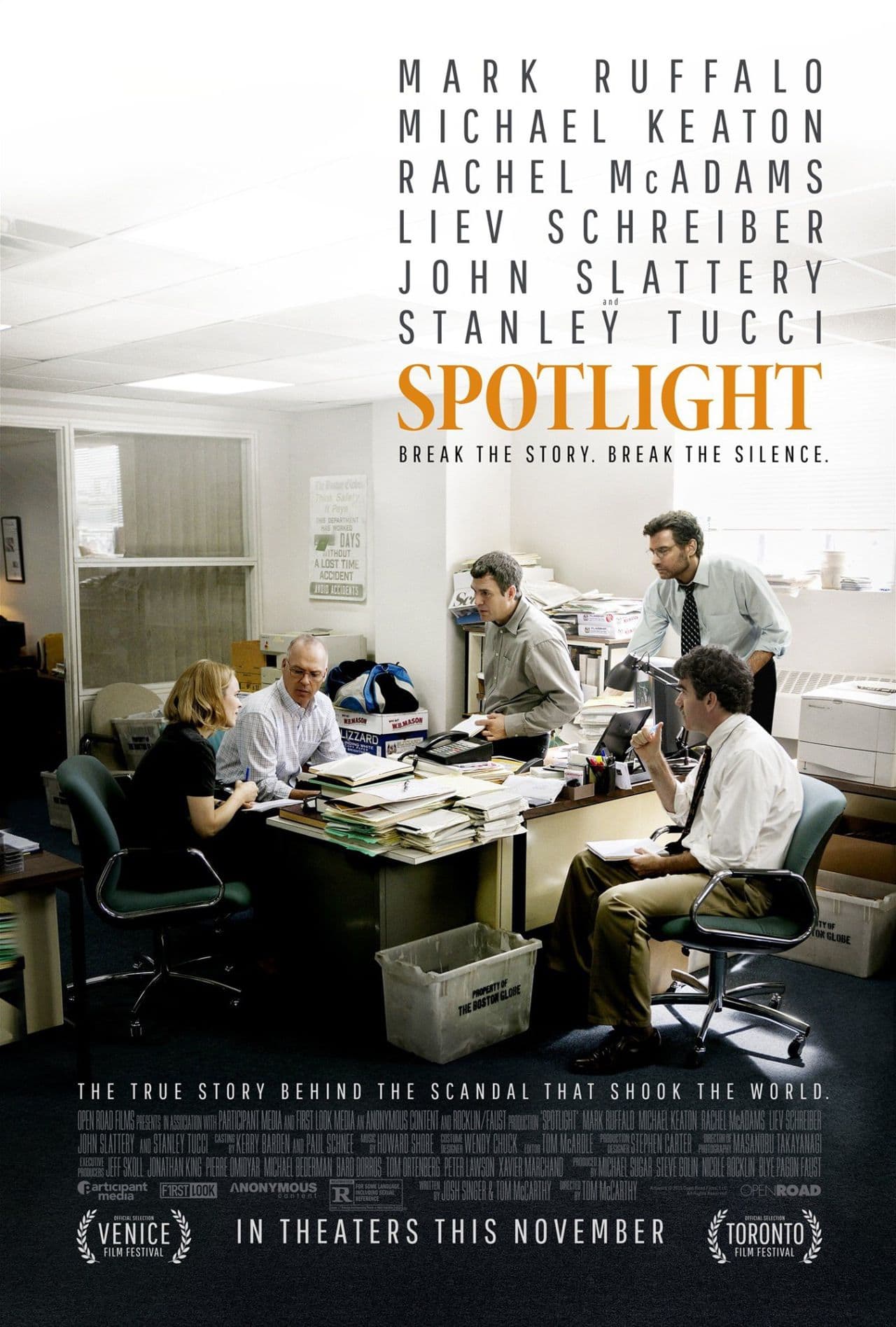

In 'Spotlight,' Investigative Journalism Gets Its Due

"Spotlight," the new movie about The Boston Globe's investigation of widespread child molestation in the Catholic Church, has been compared favorably to “All the President’s Men,” the tale of the two heroic reporters who broke the Watergate scandal for The Washington Post. Both films are talky, true-life procedurals about the grinding, essential work of investigative journalism. Both films show how a free press can expose the corruption in powerful institutions.

The dirge for investigative journalism has been sounding for years, and though it endures in a few places, overall the costly practice is clearly on life support.

But as I watched the terrific “Spotlight” at its premiere this week, one difference was unavoidable. In 1976, when “All the President’s Men” was released, the journalism profession was triumphant, or at least deeply satisfied, in its role as national watchdog. In the era of “Spotlight,” the mood can only be called elegiac — the film felt like an artifact of an earlier time, barely a decade ago, when newspapers were strong enough to provide an effective check on otherwise unaccountable power.

The dirge for investigative journalism has been sounding for years, and though it endures in a few places, overall the costly practice is clearly on life support. Newspapers have been bleeding staff for a decade at least, and the labor-intensive investigative teams are often the first to go. No one else — no website, no nonprofit, not even Wikileaks — has filled the gap. Local television “I-teams” have dried up like leaves in an autumn wind. Membership in the trade association Investigative Reporters and Editors dropped by 25 percent between 2003 and 2010; Pulitzer Prize entries in the investigative category have fallen 21 percent since 1985.

Investigative journalism is a leap of faith by news organizations that an investment of money and personnel — sometimes, as in the Globe’s case, lasting many months — will pay off with a significant scoop. It’s expensive to sue the Archdiocese of Boston, interview hundreds of sources, read cratefuls of dusty reports, and pry records from opaque institutions, and the Globe likely spent well over $1 million in labor and legal costs on the investigation. (Full disclosure: I was an editor in charge of the editorial page of the Globe at the time.)

The movie “Spotlight” faithfully depicts the commitment and drive of the Globe reporters to keep digging when records disappear or anguished family members angrily block their access to victims. Newsroom editors and the publisher have the steel to back them up in the face of the inevitable church backlash. Victims overcome their shame and misgivings to offer searing testimony about trusted priests who preyed on them as children.

if this respectful, honest tribute can restore some of the shine to a struggling profession and remind the public why quality journalism is worth paying for, it’s a start.

In the film, Spotlight team reporter Matt Carroll discovers that a “treatment center” for pedophile priests has been quietly operating in his residential Boston neighborhood. On the January morning when he smacks a hefty Sunday Globe with its Spotlight headline “Church allowed abuse by priest for years” on the center’s doorstep, the audience cheered, and tears sprang to my eyes.

A blogger with a slingshot can hit the occasional target, but the kind of sustained, broadly read coverage that can change entrenched policies and practices can only be provided by a robust news organization. Ultimately the Globe published more than 600 stories in its series, which won the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for public service. As “Spotlight” director Tom McCarthy said recently, “It takes institutions to watch institutions.”

It’s true that some enterprise journalism has migrated along with readers to digital platforms, including mobile devices, but the audience for that is still fragmented. Universities and nonprofits such as ProPublica have provided a critical lifeline. Boston University, Northeastern and Brandeis all maintain investigative reporting centers that train a new generation of journalists and provide legwork for “mainstream” press reports. Public television’s “Frontline” and NPR, often working with the new nonprofits, can dig deep into shadowy areas of national interest. And of course the Globe Spotlight team continues against steep odds to break important stories.

But the clock is ticking.

After the credits rolled at the premiere, the actors and their real-life counterparts took the stage. Former Globe editor Marty Baron, depicted with understated accuracy in the film (and now with The Washington Post), thanked the audience and made a simple request. “Our highest mission is to hold powerful institutions accountable,” he said. “Please support that.”

The movie “Spotlight” may not spark massive new spending on investigative journalism or fix the broken business model that no news organization has yet to solve. But if this respectful, honest tribute can restore some of the shine to a struggling profession and remind the public why quality journalism is worth paying for, it’s a start.

"Spotlight" opens in select theaters on Nov. 6.