Advertisement

Strangers: Fear Fills The Space Between A White Man And A Muslim Woman

“Go home!” the man screamed at me. We were on the Anderson Memorial Bridge above the Charles River, I in my headscarf and polka dot backpack, he in his blue jeans and sweatshirt. I stopped walking. He stared at me, full of anger. A white man. A Muslim woman. My mind went blank. Instinct told me to run. I crossed the bridge in the direction of Harvard, where I am studying for my masters, by sprinting as fast as I could.

Just a few months before, my mother, upon hearing of my plans to study here, had said, “Are you sure you want to study in America? It might be dangerous.” What she said shocked me -- I have always dreamed of studying at Harvard — but I understood. At home in Indonesia, a Muslim girl in a hijab is typical. Eighty percent of Indonesians are Muslim. But in America, my headscarf signifies to many either oppression or that I am a potential terrorist.

The incident on the bridge occurred about a month into my otherwise happy school year, just as I had been thinking that my mother’s fear for me would go unrealized. That frightening moment told me that I do not belong here. Since Sept. 11, 2001, Americans have looked at Muslims with suspicion. Here, I am “other.”

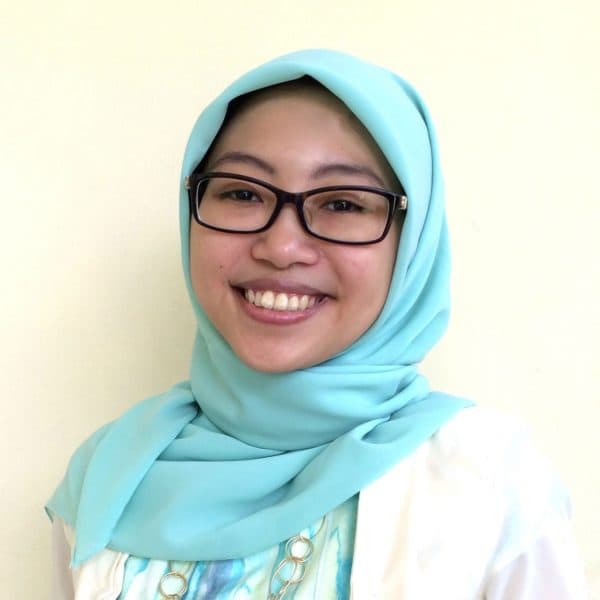

In class that day, my mind was disengaged. I was puzzled. How could a stranger have so much hatred and anger toward me? Could a 4-foot-9 woman really pose such a threat? That day, I realized how different I am from the rest of my classmates. Not only am I the only woman in a hijab in my class, I am one of only two women who wear a headscarf — the other is American — in my masters program. For the first time since arriving at Harvard, I wondered how my fellow students, who hadn’t treated me differently, might really feel about me. I wondered if, like that man on the bridge, they found me threatening, but chose to say nothing.

...my mother, upon hearing of my plans to study here, had said, 'Are you sure you want to study in America? It might be dangerous.'

One recent day in class, the topic was the headscarf bans in Turkey and France. I was keen to hear how the intellectual discussion would play out -- were the courts’ decisions to ban headscarves legitimate and morally justified? When the professor asked the class whether a woman is justified in wearing a headscarf in spite of the ban, no one commented, but a few students glanced at me.

“Why don’t we ask Dhani?” the professor said. “Why does she wear a headscarf?” Everyone was silent. All eyes were on me. “You don’t have to answer if you don’t want to,” he added.

I have never believed that an individual should have to represent a group, be it a race, a religion or a sexual preference. But I knew it was not a choice. I took a deep breath and answered him. I said that wearing a hijab is an individual decision, and that I do so because doing otherwise for me would be a sin.

That gap of understanding is often filled with hatred. And why wouldn’t it be? Muslims make up scarcely 1 percent of the U.S. population. Many Americans have never met a Muslim. Muslims are rarely presented in mainstream media. When they are -- see Homeland, for starters -- they are, inevitably, terrorists.

But believers of every faith should be seen and assessed as individuals, not as a homogeneous group. There are roughly 1.6 billion Muslims around the world. Thinking that Muslims are all the same -- shouting at one to “go home” or asking her why she wears a headscarf to explain why other Muslims do -- is not just illogical, it’s ignorant.

When you don’t understand, you fear. When you fear, you hate. When you hate, you distance yourself.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s proposal to ban Muslims from entering the U.S. is a perfect example. It is a reaction of fear towards the unknown, the other. When you don’t understand, you fear. When you fear, you hate. When you hate, you distance yourself. And the more distant you are, the less you understand. It’s a cycle.

We need to build and cross the bridge of otherness. The only way to build that bridge is through interaction. We need to know the other for her no longer to be a stranger in a headscarf, but a fellow human.

I had to cross the bridge again to go home that day. It was dark, full of pedestrians and packed with traffic. I know that crossing the bridge is not always safe, but as I walked, I realized that I have made a choice. This is home to me now, so I will continue crossing that bridge.