Advertisement

Rewriting The Narrative To Suit Their Storyline — It's The Clinton Way

Before the Iowa returns were even final, Hillary Clinton took to the stage and declared victory. It was an audacious move, one that infuriated supporters of Bernie Sanders and got some pundits huffing about “spiking the ball on the five-yard line” (that from MSNBC’s "Morning Joe"). It was also politically brilliant. And if it seems somewhat familiar, it should: It comes straight out of the Clinton political playbook circa 1992 — and it’s a ploy we may well see again come next Tuesday.

In 1992, Hillary’s husband, Bill, was running for the Democratic presidential nomination, desperate for a win in New Hampshire that would let him stand out in a corded field. Early polls looked good. A mid-January survey conducted by The Boston Globe, for example, put Clinton at 29 percent while Paul Tsongas, the former U.S. senator from neighboring Massachusetts, was at just 17 percent, nearly tied with the 16 percent going to Nebraska Sen. Bob Kerrey.

In truth ... The caucus results were an enormous comeuppance for Clinton, a humiliation even.

But then came the so-called “bimbo eruptions.” Stories about Clinton’s numerous alleged extramarital affairs surfaced. His numbers plummeted. The Clintons -- husband and wife — desperately fought back, including an agonizing and embarrassing appearance on CBS’s "60 Minutes" immediately following the Super Bowl.

It was to no avail. Tsongas surged ahead and won New Hampshire with 33 percent of the vote. Clinton was far behind, at just 25 percent.

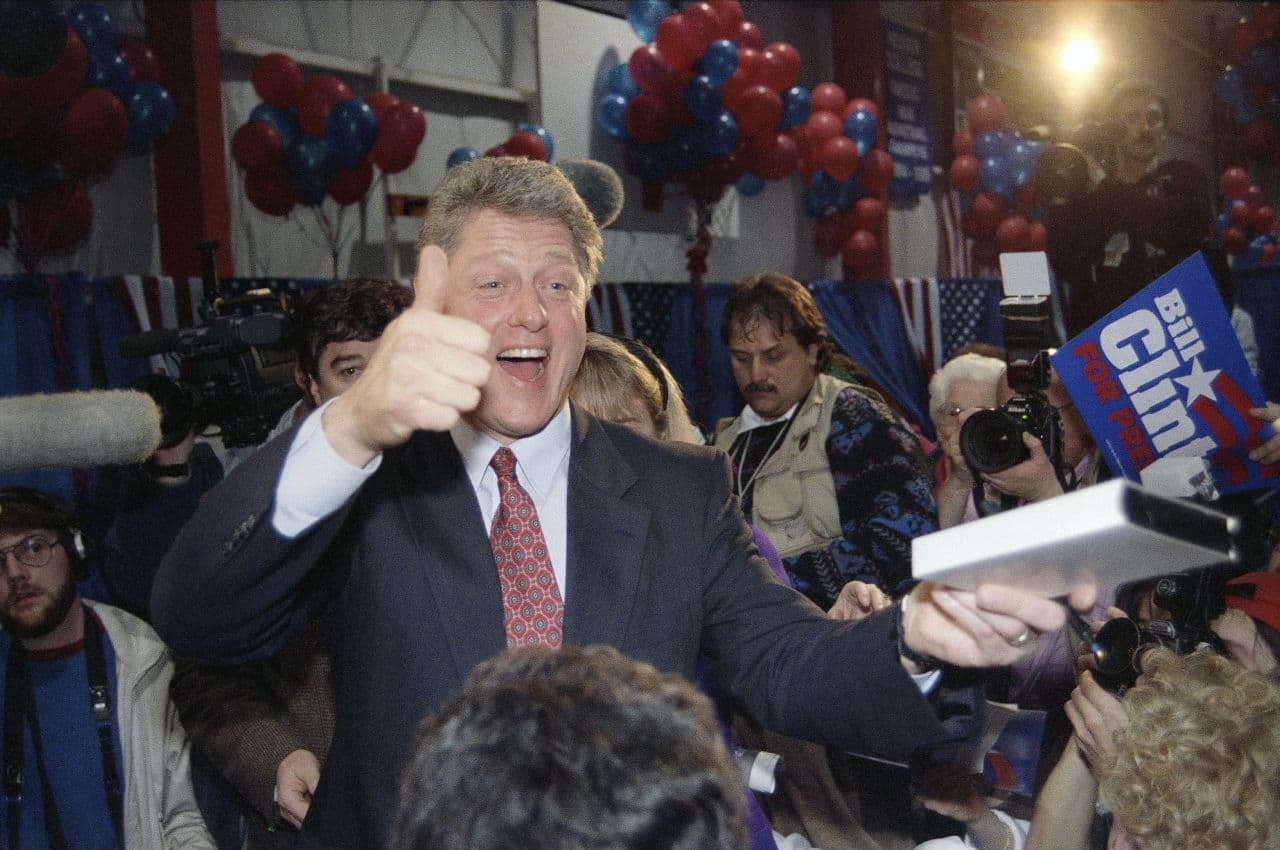

Clinton’s run for the nomination should have been over at that point, but in an extraordinary display of hubris, he took to the airwaves and — under the logic that he didn’t lose by as much as he might have — declared himself “the comeback kid.” By the time Tsongas finally made an appearance, the storyline had been set: Clinton had somehow pulled off an upset. The rest, as they say, is history (although not a smooth history; Clinton didn’t clinch the nomination until the June 2 primary in California).

What Hillary Clinton did in Iowa was a replay of 1992. In truth, it was Sanders who “won” on Monday. In the months leading up to the caucuses, Clinton had been well ahead in Iowa. At the beginning of this year, for example, she was besting Sanders 50 percent to 38 percent, according to Real Clear Politics’ averaging of polls. Even in the closing days before voting began, Clinton still had a lead of 4 points. The final result — Clinton had a margin of just 0.3 — was basically a tie. Sanders was right when he said he had been successful in taking “on the most powerful political organization in the United States of America.” The caucus results were an enormous comeuppance for Clinton, a humiliation even.

But with her claim of victory — not tie -- Clinton was rewriting the narrative. As the Clintons know well, politics is about intangibles such as momentum, expectations, perceptions and morale. By getting out in front of the story, Clinton was turning the lemons of Iowa into some sort of lemonade.

It will be interesting to see how that lemonade goes down in the Granite State.

As the Clintons know well, politics is about intangibles such as momentum, expectations, perceptions and morale.

There’s little question that Clinton will lose the popular vote in New Hampshire to Sanders. The real question is, by how much? A UMass Lowell/7 News poll conducted at the end of January showed Sanders with an overwhelming lead of 33 over Clinton. If the numbers on Tuesday match that prediction, then there’s probably little that the Clinton camp can do to put lipstick on the pig. They’ll declare the results meaningless, chalking up Sanders results as home-field advantage (since Vermont is adjacent to New Hampshire) and pointing out — quite correctly — that the white liberal demographics of the state’s Democrats hardly reflect the demographics of the nation. Bill Belichick-like, they’ll resolutely turn their eyes to the next contest: “We’re on to South Carolina.”

But should Clinton lose by less than 33 points? Don’t be surprised to see her on-screen, just in time for the 11 o'clock news, claiming that this time she’s the “comeback kid” or some variant thereof. Yes, Sanders will have tied her in Iowa and beaten her in New Hampshire, meaning that he’s the one with the most delegates. But Hillary will claim momentum nonetheless and roar on into Super Tuesday. Will it work? Most likely. It’s the Clinton way, tested and true.