Advertisement

Commentary

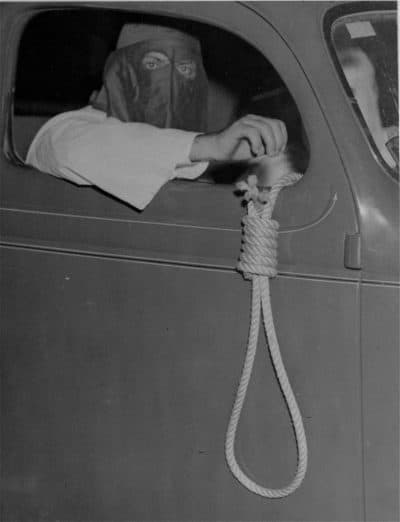

Is The Noose, A Symbol Of Racial Terrorism, Returning?

The Obama presidency was marred by the murder of young black boys and men at the hands of law enforcement, which evoked the apothegm that black lives matter. Oscar Grant III, Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray: That list goes on and on.

In 2015, at least one person was killed by police in each of the 50 states, including the District of Columbia, and black men were nine times more likely to be victims.

As the Trump presidency begins, are we experiencing the era of the lynching noose, a dreaded weapon and symbol of racial terrorism?

Perhaps.

In May, a noose was found in the newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture. It was left in the section of the museum that highlighted the history of segregation, America’s apartheid. It was the second of three nooses left in Washington, D.C., this spring.

In an op-ed in the New York Times weeks later, Lonnie Bunch III, founding director of the museum, called the noose a despicable reflection of “racial violence.”

“The person who recently left a noose at the National Museum of African American History and Culture clearly intended to intimidate, by deploying one of the most feared symbols in American racial history,” wrote Bunch.

“Instead, the vandal unintentionally offered a contemporary reminder of one theme of the black experience in America: We continue to believe in the potential of a country that has not always believed in us, and we do this against incredible odds.”

Bunch is trying to encourage us. But what’s plainly discouraging is that the noose is being brought to use again across the country in recent months.

Earlier this month a noose was found hanging in a tree in downtown Philadelphia. Authorities are looking for a white man caught on video hoisting the noose between tree branches. A black man joins the suspect as they travel away from the tree.

A federal employee in Philadelphia was also intimidated — terror-struck — when a noose was placed on her desk at that city’s mint.

According to the Huffington Post, the use of the noose is becoming a nauseating national trend: “Nooses were also found at a frat house at the University of Maryland, a middle school in Florida, and at two high schools in separate incidents in North Carolina. A Walker, Louisiana, police officer resigned in March after leaving a noose in the department’s squad room.” In May, less than a day after Taylor Dumpson because the first black student president, several bananas hanging from nooses appeared on the American University campus.

The lynching noose is a blatantly offensive artifice, especially to generations of African-Americans who are aware of its history. The noose is a symbol of an odious ideology of human hierarchy that denotes domination of one group of people over the other, namely whites over blacks.

Between 1882 and 1968, at least 3,446 black people were lynched in the United States, according to the NAACP. Stated more dramatically, blacks accounted for 72.7 percent of all recorded lynchings, even while they represented no more than 12 percent of the population during that period.

Called the “Negro holocaust,” the extended practice of lynching in America was a cultural policy performed through varying methods that included shooting, strangulation, stabbing, drowning and especially hanging. Few have captured the tragic dimensions of lynching in the broader popular culture than the jazz singer Billie Holiday, whose performance of the song “Strange Fruit” in the 1940s shocked the nation to its spiritual core and galvanized sentiment against the brutal practice.

Lynching represents white supremacy, which the theologian Drew Hart has described as a “sociopolitical collective that created [an] artificially constructed group ... ” Yes, racism is a social construction and as such, it is also evil.

The irony of America under its first black president is that the country had seemed to reverse itself on matters of race. While many of us thought that the Obama presidency would bring about racial advances, it appears that the opposite has occurred. We have backslidden on race, reversing the slow, inexorable progress we seemed to make since the civil rights movement.

It seems that our racial healing is not quite at hand. In fact, on matters of race, things may get worse before they get better. The use of the lynching noose seems to indicate that racial resentment and animus still smolder on the periphery — if not the very center — of public life in America. Irrepressible and persistent, racism remains prominent in the public imagination of the country. It clings within the culture with undiminished tenacity.

The killings of black men are so telling of how much ground we must cover to finally arrive at what Congressman John Lewis calls “the beloved community,” where the pornography of racial hatred is challenged and finally reduced to a shadow of its current incarnation.

And so we must be vigilant as the powerful symbol of the lynching noose is evoked to frighten and intimidate. We must stand against its ugly symbolism and continue to seek a country committed to the best ideals of race, characterized by the realization of equality and genuine notions of brotherhood and sisterhood.