Advertisement

Commentary

Cracking His Code: A New Memoir By The Daughter Steve Jobs Denied

Any origin story of the personal computing revolution would need to mention Apple founder, Steve Jobs. And like any good creation narrative, this myth has its conventions. Bright, innovative thinker labors on a project without any immediate promise of commercial gain — yet instead is propelled forward by the desire to change the world. He (because it is usually a he) moves into the spotlight, gradually assuming a larger-than-life status that is only amplified by known details of his quirks and personal habits. These features, visual and otherwise, taken together, begin to construct a public persona that serves as a stand-in for the person in question. In the case of Jobs, it was his jeans and black mock turtleneck, his macrobiotic diet, and his often-unforgiving personality that rendered him recognizable. But, as is often the case, there is a gap between the public and private.

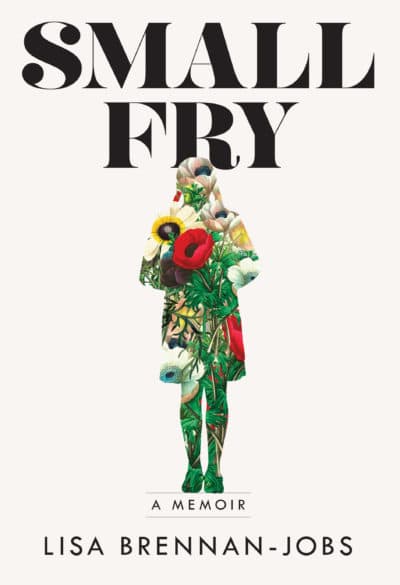

In Lisa Brennan-Jobs’s new book, "Small Fry," readers catch a glimpse of the background story that runs parallel to her father’s rise. But if some might expect a celebrity tell-all, they will be disappointed. There is not much revealed that would surprise one familiar with the tech giant — especially if they’ve read Walter Issacson’s 2011 biography or seen its film version. Because "Small Fry" is not Steve Jobs’s story. Nor is it simply the author’s story. It is, though, a classic bildungsroman — a narrative that charts the development and maturation of its protagonist. And Brennan-Jobs's story is situated within a universal context: a daughter coming-of-age under the shadow of an omnipresent yet remote father whose approval she desperately seeks.

Jobs and his girlfriend Chrisann Brennan were in their early 20s, yet no longer a couple, when Lisa was born. And though for years he carried around her photo in his wallet, often pulling it out to show colleagues and acquaintances, he denied paternity, even after subjecting his young daughter to a test that provided confirmation. He even named his first computer The Lisa, an uncharacteristic expression of sentimentality that he later he denied held any connection to his daughter. At one point, young Lisa musters up the courage to ask her father if it is true, that the computer was named after her — clearly searching for some outward sign of validation or belonging. After all, she is trying to establish her own creation myth. But Jobs tells her, dismissively, that it was named after an ex-girlfriend. She is deflated. (It was only years later, when questioned by U2 frontman Bono in Lisa’s presence that he admitted the connection.)

This continued quest to belong to a man so obviously uncomfortable with intimacy is what prompts Lisa to add her father’s last name and leave her mother’s home as a young teenager to stay with the man she calls Steve and his growing family. He lives closer to school, she is arguing with her mother, and moreover — she wants to feel like his daughter. But her stay comes with conditions: Lisa is not allowed to have contact with her mother for six months. His argument is that is the only way that she will fully bond and hence, belong with and to the new family. She agrees.

As a developer, Jobs knew well the concepts of value proposition and any choice’s inherent tradeoffs and while reading, I could not help viewing this through that disciplinary lens. The problem though, is that one can’t run a beta test on a child’s life. And Lisa was not receiving any of the affordances of access to her father, even as she worked within the constraints he required. Thought Brennan-Jobs resists many opportunities throughout to condemn her father for his coldness, she provides us with highly attuned observations that allow the reader to fill in the gaps, extracting meaning and forming opinions.

As new half-siblings are welcomed to the family and their rooms are upstairs next to their parents, teenaged Lisa begins to feel her distance from the nucleus of the family. When she is given a choice as to which room she could have on the ground floor, she chooses the one closest to the kitchen since at least that way she would see everyone. Family photo shoots exclude her, so too does his official Apple bio. But her requests remain small. She asks her father to come in and say goodnight to her. It happens once. And it is never discussed again. Soon after, they visit Lisa’s therapist and she tearfully shares with Steve and his wife Laurene that she is lonely and wants their affection. Her stepmother’s response: “We’re just cold people.”

It is important to note that this book also reads as a love letter to the pre-Internet Silicon Valley — a place populated by idealism, environmentalism, and genuine intellectual curiosity. There are also glimmers of brightness — as Jobs and Lisa roller skate through tree-canopied pathways on the Stanford University campus, or enjoy the ephemeral feeling of jumping on a backyard trampoline.

But this book can also be hard to read — as it draws from the well of father archetypes, Jungian and other, that are almost wholly negative. "Small Fry" reveals a man unable or unwilling to assume the role of doting father, or even avuncular advisor but Brennan-Jobs does not force that depiction. Rather, this shadow narrative of Jobs’s first real prototype (Brennan-Jobs) has built in the incisive details, collected, batched and then processed by an adoring daughter who has fully claimed her birthright.