Advertisement

Running To Support Schizophrenia Research As Federal Funds Dry Up

When Dr. Robert Laitman lopes by in Monday’s Boston Marathon, the guy in bib #6149, you could see him as just another runner with a cause, a father hoping to help his schizophrenic son. He’ll be raising money for the schizophrenia genetics work at McLean Hospital’s Psychology Research Lab, in hopes it will help his son, Daniel, and many others.

But you could also see Rob Laitman’s 26.2 miles as reflecting something far broader: the federal funding crunch that is hurting even some of the best-established laboratories across the nation.

Massachusetts, with its august academic institutions, has long received more National Institutes of Health money for biomedical research than any other state. And Harvard’s McLean Hospital is a psychiatric research powerhouse. Its program totals about $40 million a year, three-quarters of it from federal grants. That’s more than any other private psychiatric hospital in the world.

But no one is immune. Consider Rob Laitman’s marathon fundraising letter. It begins:

“I am writing to ask you to help a very dear friend and colleague. Apparently after 20 years of being funded, Deborah Levy’s last grant application for her lab was not accepted. She is presently trying to find funding from other avenues and is also reapplying to the NIH. Deborah does critical work in basic schizophrenia genetics. She has been making continuous headway and in fact just contributed to a seminal article that was published in Nature. As director of the Psychology Research Laboratory at McLean Hospital, (Harvard’s Psychiatric Division), she has been universally loved and respected.”

The Psychology Research Lab has been funded since 1978, largely by federal grants as well as private grants and McLean money. It has gathered a priceless pool of families with multiple members who have schizophrenia or other mental illnesses, and has helped pioneer efforts to find important risk genes.

But in this funding climate, there are no guarantees. I asked Dr. Thomas Lehner, director of the Office of Genomics Research Coordination at the National Institute of Mental Health, about the lab’s plight. He could not comment directly on any specific grant, but said, “That’s not the only outstanding lab that finds itself in that position, and it’s unfortunate.”

I asked what he was hearing from labs around the country. “I hear a lot of pain,” he said, “and a lot of concern that good science is just not being funded. I hear that labs are closing. I hear that budgets are insufficient. That has always been a concern, but it’s more pronounced now. And I share the pain of the investigators.”

The news could be even worse, of course. Some in Congress had proposed slashing the National Institutes of Health’s budget by $1.6 billion this year, but the latest budget deal cuts it by only about $300 million. Still, those cuts come on the heels of years of flat or declining budgets. Thomas Insel, chief of the National Institute of Mental Health, wrote on his blog last month that to scientists, these tight times “may feel like a funding desert.”

Please indulge me in a brief rant.

This whole story brings to mind a bumper sticker I used to see around: “It will be a great day when our schools get all the money they need and the Air Force has to hold a bake sale to buy a bomber.” If anybody asked me whether I wanted federal money to fund another bomber or more research into a devastating mental illness that affects 1% of the population, I would not be choosing the bomber. Thank you. End of rant.

I wrote about the Psychology Research Lab’s work back in 2007 for the Boston Globe. When I went back to visit Deborah Levy this week, she was plugging away amid piles of paper and grant proposals — her own, and those of other researchers whose applications she must evaluate for a federal funding panel.

She’s not giving up, and she has some “bridge funding” from McLean to keep the lab open. But this is a heart-wrenching time. One colleague who had worked with the lab for 29 years recently had to take another job.

“The irony,” she said, “is that now, for the first time, after years of looking, researchers are finally beginning to find risk genes with large effects. If there is any time for translating discovery into treatments and potentially into cures, it is now.” And yet, she said, because funding has so dwindled, her lab “is at a near-standstill.”

One particularly tantalizing opportunity: She and colleagues recently found a mutation in two members of a family that suggests a clear target for a potential schizophrenia treatment. She hopes to be able to set up a treatment trial soon — assuming she can get funding. If it worked, she said, “it would be the first proof of principle in psychiatry that a specific mutation can become the basis for a rational treatment intervention.”

In a statement responding to my query, McLean Hospital, too, talked about irony:

“As a non-profit organization, external support, through federal grants, industry, and foundations as well as private gifts, is vital to our ability to sustain a robust and innovative psychiatric research program. We are making extraordinary advances in psychiatric research each day. It is ironic that at a time when the science has never been more exciting and promising, economic factors have constrained and threatened the pace of progress in the field. Nevertheless, we remain fully committed to conducting research that will improve the lives of our patients and their families and thanks to the full range of resources available, including the generosity of philanthropic individuals, we are able to continue this important work on a large scale. We are thankful to all of our friends and supporters who believe in McLean and its precious mission.”

After so many years of working with hundreds of families intent on helping loved ones with schizophrenia, the Psychology Research Lab has a strong set of its own “friends and supporters.”

As word spreads of the lab’s funding drought, some of those families are joining forces to try to raise private money to support it. The idea, Deborah Levy said, is to create a public-private partnership that would help raise the several million dollars needed to let the lab’s work go forward even with much smaller federal grants.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]If there is any time for translating discovery into treatments and potentially into cures, it is now.” And yet, she said, because funding has so dwindled, her lab “is at a near-standstill.”[/module]

“In order for us to be able to do the work, we need to find additional sources of funds,” she said, “and that’s where we’re hoping private philanthropy, and the kinds of efforts the Laitmans are making — which are really quite extraordinary — will be fruitful.”

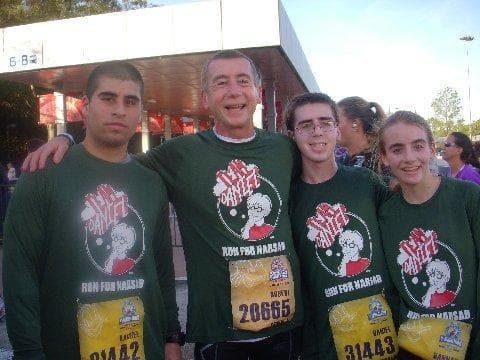

Dr. Robert Laitman, who is a kidney specialist in New York, will be running with Ralf Hennig, who was long Bill and Hillary Clinton’s personal trainer, to raise money for the lab, he said. He has been spreading his “Team Daniel” fundraising letter far and wide, emailing "friends, colleagues, long lost friends, old buddies, old crushes, patients who love to email," anyone who might be able to help.

Rob and his wife, Ann, also a physician, have four children. Daniel, their second, developed schizophrenia at the unusually young age of 15, hearing voices and commanded by irrational compulsions. The Laitmans embarked on a long, tortuous medical and psychiatric journey. Through stunning serendipity — both sets of Daniel’s grandparents knew people who knew Deborah Levy — it led them to her lab four years ago.

Her genetic research struck Rob as relevant, he said, because his own family tree is rich in relatives with mental illness. And she has served as a valuable adviser on care for Daniel, who now, at 20, is in school and doing well on a strenuous regime of medication and exercise.

She never asked for help on her lab’s funding, Rob stressed: “This is us coming to her.”

If her work ended, he said, “It would be a tremendous loss because she’s starting to really make some significant inroads” into schizophrenia genetics.

So many important questions remain, he said: Can we use genetic testing for schizophrenia? If someone is at high genetic risk of schizophrenia, can it be prevented? Is gene therapy possible? Will genetic studies suggest whole new avenues of possible treatments, as the recent Nature paper did?

“There’s so much research to be done, and it is such a debilitating illness and such a costly illness,” he said. The Psychology Research Lab “cannot be allowed to fail. It would be a disgrace.”

Please click here for a brief Marathon morning video interview with Rob Laitman.

Deborah Levy is at dlevy@mclean.harvard.edu.

This program aired on April 15, 2011. The audio for this program is not available.