Advertisement

From First Cold To Grave: How Two-Month-Old Brady Died Of Pertussis

Brady Alcaide — a happy, healthy six-week-old baby — got his first cold shortly after the new year.

His mother, Kathy Riffenburg, had seen her share of sniffles (she has two older daughters, 8 and 5) and didn't think much of it. "It was just a little cough and sneeze," she said. "I wasn't too worried."

But a few days later, on January 6, Brady's fever spiked to 104 degrees. So, in the middle of the night, Riffenburg and her husband Jonathan decided to take the baby to the emergency department at Baystate Children's Hospital in Springfield, Mass. near their home in Chicopee. Brady tested negative for flu and a common respiratory virus. By early morning, his fever was gone and the family was sent home.

Three weeks later Brady would be dead, a victim of pertussis, or whooping cough, a preventable but highly contagious bacterial disease that has been on the rise in recent decades.

At home, Brady's breathing became slightly more labored; he'd been diagnosed with bronchiolitis, a swelling and buildup of mucus in the tiny air passages of the lungs, usually due to a viral infection. After another examination later in the week, a pediatrician prescribed albuterol to ease Brady's symptoms.

On January 16, the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, Brady started spitting up more and his breathing worsened. This time he was admitted to Baystate's pediatric ICU, his mother said. A medical team assessed him; and an infectious disease doctor suggested he might have pertussis, though the diagnosis remained uncertain. Indeed, the family didn't get confirmation of Brady's pertussis until after his death, when a test for the disease came back positive. "I could have bet my whole life that it wasn't pertussis," Riffenburg said, recalling her reaction when the illness was first mentioned. "He wasn't coughing like I would have imagined. And I didn't know any infant who ever had pertussis."

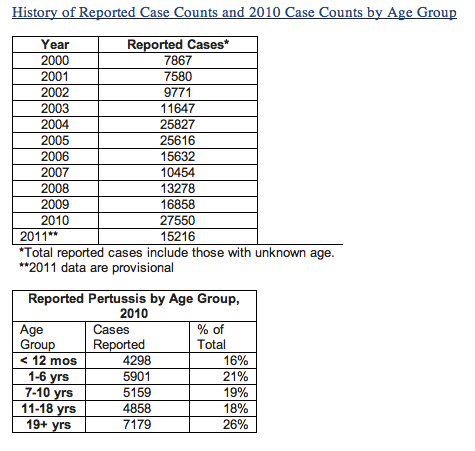

But pertussis, or whooping cough, or "the cough of 100 days" for its generally long duration, has been on the rise since the 1980s, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease is characterized by violent, uncontrollable coughing (including the characteristic "whoop" sound) that can make it hard to breathe. But sometimes there is no "whoop." And infants with pertussis don’t always cough, but may have apnea, a long pause in their breathing. The disease is most common in young children; babies under one are particularly vulnerable and face the greatest risk of death.

In 2010, there were 27,550 reported cases of pertussis nationally, the CDC says. That year, in California, 9,143 cases of pertussis — including ten infant deaths — were reported, the greatest number of cases in 63 years, according to the CDC. Vermont had a pertussis outbreak last year. And on April 3, Washington State officials declared a pertussis "epidemic," with over 1,000 cases reported.

The CDC recommends pertussis vaccines for infants, adolescents and adults (most recently, pregnant women), summarized here:

Infants and children are recommended a dose of DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and Acellular Pertussis) vaccine at 2, 4 and 6 months, 15 through 18 months, and 4 through 6 years of age. Everyone 11 years and older, including pregnant women, is recommended one dose of Tdap (combined Tetanus, Diphtheria and Acellular Pertussis) vaccine, preferably at 11-12 years of age. Pregnant women are recommended to receive a dose of Tdap vaccine, preferably during the third trimester or late second trimester (after 20 weeks gestation). By getting Tdap vaccine during pregnancy, maternal pertussis antibodies transfer to the newborn, likely providing protection against pertussis in early life, before the baby starts getting DTaP vaccines. Tdap will also protect the mother at time of delivery, making her less likely to transmit pertussis to her infant.

A CDC spokesperson adds: "Everyone needs Tdap vaccine as an adolescent/adult even if they were fully vaccinated with DTaP or DTP vaccine as a child."

What, exactly, is driving the increase in pertussis cases isn't totally clear. Experts speak of a convergence of factors, including waning immunity after vaccination, low vaccine compliance among adults (who had coverage rates of only 8.2 percent in 2010, according to the CDC) and a general perception that whooping cough isn't a dire condition. Another factor may be that pertussis is going undiagnosed in many cases — since not everyone “whoops” — allowing for disease to spread. In addition (though the CDC disputes this) declining use of antibiotics by doctors wary of overuse and drug resistance may also be a cause.

Some put the blame on parents who refuse to vaccinate their children. But officials at the CDC say it’s more likely that declining protection in vaccinated people rather than vaccine refusal is contributing to the increase.

At first, Brady (who was scheduled to have his first immunizations, including the vaccine for pertussis, on January 27) began to improve — the hospital staff even moved him to a room with three other roommates. After eight days in the hospital, Brady started a course of antibiotics; and a formal pertussis test was conducted, his mother said. He was then moved back into a single room.

That's when things got really bad. On January 23, doctors inserted a breathing tube; on the 24th they changed his ventilator. "His CO2 levels are on the high side," Riffenburg wrote on her Facebook page, where she had been updating far-flung family members.

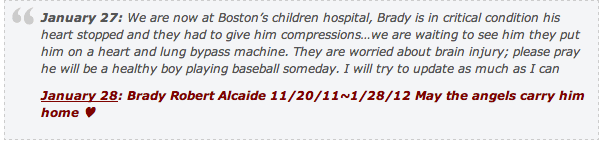

It became harder to keep Brady stable, she said, so on January 26 two new doctors were brought in to assess him. Within hours, one of them said the boy had to be rushed to Boston Children's Hospital because Baystate didn't have the necessary equipment to handle Brady's deteriorating condition. Unable to fly to Boston from western Mass. due to weather, the family was left to travel by ambulance. Riffenburg said it took three hours to stabilize her son for travel and staff told her he had a 50-percent chance of surviving the 90-mile trip. A priest finalized a rushed baptism as Brady entered the elevator en route to the ambulance.

He almost didn't survive the road trip. At exit 11 off the Mass. Turnpike, just outside Boston, Brady stopped breathing and his heart rate declined, Riffenburg said. A Children's Hospital team met the ambulance on the highway and started doing compressions on the baby until they pulled up to the hospital where surgeons were waiting.

Doctors were able to get Brady on the heart-lung bypass machine, but by this time, his brain had already been deprived of oxygen and it was unclear how much damage was done.

Early in the morning of January 28, Riffenburg took a shower and rushed to Brady's room. "He was very still — and he was puffy, very red. His foot was purple — it didn't look like him," she said.

After several long, hard discussions about Brady's lack of substantive brain activity and the increasing difficulty of sustaining his blood pressure, a decision was made to take him off the machines. "We went into a room, said a couple of prayers, annointed him with oil and at 2:53 they pronounced him in my arms," Riffenburg said. "I had to say goodbye to my baby. Then we had to go home that night without our son; we had to tell our girls what had happened and that Brady wasn't coming home."

Now, the family hopes to raise awareness about the dangers of pertussis through a site they created called Brady's Cause. They want to reiterate the importance of childhood vaccinations, and in particular, tell every adult they know to get the vaccine. "A lot of adults, we don't think about that," Riffenburg said. "My husband was saying, when you have a newborn baby, you're so caught up in the moment, if no one tells you to get a vaccine, you just don't think of it."

Riffenburg, a 29-year-old counselor at an after school program for kids, does not know how Brady contracted pertussis. Though most infants who develop the disease get it from an older child or adult in the family, everyone in Brady's immediate family tested negative, she said. (Riffenburg and her daughters had been vaccinated; their father wasn't but now is.)

Because pertussis is a preventable infectious disease, the state Department of Public Health has launched an investigation to try to pinpoint exactly where and how Brady got infected and if appropriate, provide treatment. John Jacob, a spokesman for the agency, says that since 2006 the state has reviewed 281 cases of pertussis in infants and of those, the source has been determined in about 65 percent of the cases. (Of the cases identified, family members were most often the source, he said. That's why public health officials are pushing the concept of "cocooning," that is, making sure all of the people around the infant are immunized.)

But Riffenburg said the state health investigator assigned to her case isn't terribly optimistic about finding the source. "She said there is no way we will ever know where Brady contracted whooping cough."

This program aired on April 27, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.