Advertisement

Life Of Riley: Choosing To Try Though Nothing Else Has Worked

This is the fourth installment in a special CommonHealth/WBUR series, The Life of Riley: A Rare Girl, A Rare Disease. It’s the story of a remarkable nine-year-old girl born with a one-in-a-million disease that creates increasingly aggressive “lumps and bumps” on and in her body. The only treatment, so far, has been surgery. But right now, at Children’s Hospital Boston, Riley Cerabona is trying an experimental drug that may—or may not—help her.

When Riley’s 12-year-old brother, Cole, heard that she might try an unproven medicine, his instinctive reaction was pure doubt.

“My first thought is, ‘Quack, quack, quack,” Cole said. “I was just very skeptical because I had never heard of anything that could treat malformations other than operations.”

Riley’s parents had their questions, too, when they heard last year that the clinical trial would begin soon at Children’s Hospital Boston. The trial was not specifically for CLOVES, RIley’s syndrome, but for nearly a dozen other “vascular anomalies,” growths involving mis-formed blood or lymph vessels. And the drug it offered, sirolimus, (pronounced seer-o-LI-mus), though not brand new, was just beginning to be tested for this new purpose.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'I really want to be hopeful about this trial. I also feel like nothing else has worked, so why would this?'[/module]

Riley, herself, had perhaps the biggest doubts of all. All her life, she had always steeled herself to do whatever was medically necessary, but this time, she simply balked. She said no. No nasty meds and extra blood draws and missed school days for trips from her Maine home to Boston. No.

“This is a kid that has had an ungodly amount of medical intervention and I don’t think she wanted any more,” her father, Marc, said. “ And we couldn’t say this is going to do anything. We still, to this day, can’t.”

Riley’s parents wrestled with the dilemma of whether they should somehow try to force her to participate in the trial. True, it had no guarantee, but it might be her best hope, and her disease had been progressing. But how could they? The discussion and parental angst lasted for weeks.

In the end, RIley decided that if the drug might decrease the need for surgery in the future, she was willing to try it, said her mother, Kristen Davis. "In our life, I see that as a turning point in her treatment," Kristen added. "She was advocating for herself and buying into the notion of being an active participant in her own care."

Kristen understood Riley's unwillingness. “I really want to be hopeful about this trial,” she said. “I also feel like nothing else has worked, so why would this?”

Still, in the end, Riley and her family chose hope, chose to try something rather than nothing. Now, they are following through with action. They diligently keep up with the work of a clinical trial, the dosing, monitoring and paperwork, the MRIs, the treatments for side effects. And twice a day, Riley swallows the moldy-tasting medicine, an unpleasantness akin to drinking rancid oil straight.

A long way from Easter Island

Despite Cole’s initial impression of quackery, the trial is actually extremely legitimate science, run by the two largest vascular anomalies centers in the country, the founding site at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and now at Children’s Hospital Boston as well.

If the sirolimus does have any positive effect for Riley, it will mean that a substance first found in the soil of Easter Island traveled a very long distance to help a girl in Kennebunk, Maine.

Sirolimus, also known as Rapamycin, had already been federally approved to suppress patients’ immune systems after transplant operations so that the new organ is not rejected. The idea of trying sirolimus for diseases like CLOVES originated in Cincinnati, said Dr. Cameron Trenor, the Children’s Hospital Boston specialist who is overseeing Riley's trial here.

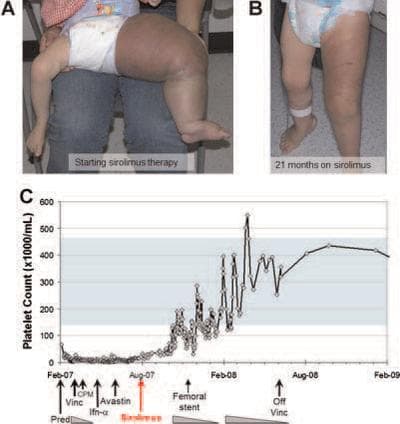

Sirolimus was known to suppress blood vessel growth, and had helped treat other benign blood vessel tumors. The Cincinnati team, led by Dr. Denise Adams, began to try it on select patients with vascular anomalies, some in dire condition. They reported in a paper last year that to varying degrees, sirolimus helped six initial patients after the standard treatments, including surgery, had failed.

The paper includes striking before-and-after photos, including one of a toddler whose leg has swelled to elephantine proportions before the sirolimus, and is considerably reduced after 21 months on the drug.

Other published papers report potentially relevant positive results with sirolimus. One, just out in the journal Pediatrics this month, describes improvement in an 8-year-old girl with a disorder called “blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome.” Another from last year describes a 6-year-old boy with "Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome." Before the sirolimus, his left arm hurt to the point that he was losing the use of it; after, he "regained pain-free full mobility."

No promises

No one is promising such dramatic results for Riley. The patients in the published papers had different syndromes, and in fact, the clinical trial she’s in is trying sirolimus for a whole array of conditions, aiming to see if it targets a pathway they might have in common. They have names like “Tufted Angioma” and “Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma.” What works for one syndrome may very well not work for another.

But in a clinical trial studying a medicine in a new way, “there should always be potential benefit” for the patient, Dr. Trenor said, and the potential benefit should be greater than the risk. Medicines have not been tried in CLOVES before, he said, but because Riley’s disease has progressed in recent years, “and she’s a young girl who has symptoms, she does stand to show some benefit.”

How soon? “It’s hard to know,” he said. “I don’t know that I honestly have an expectation.” If all goes well, Riley will be treated in the study for about a year; she will have the option of staying on the drug afterward as well.

Side effects, subtle effects

RIley is closely watched. The trial includes frequent MRIs of her spine to assess any growths there. And, Dr. Trenor said, “We ask her with questionnaires: How are you doing? What’s your quality of life like? Is what you are able to do every day different? Better or worse? Even if the lesions don’t change, if we make the symptoms better, that may be more important.”

Riley has recently reached the trial’s “goal dose” of sirolimus — the level at which patients with other, related diseases have seen benefits, he said. Now it is time to wait and see.

In the initial weeks after she started the drug in February, Riley suffered through multiple mouth sores — treated with mouthwash — and she was noticeably dragging a little, with less energy than usual. Her blood sugar tended toward the low side. Kristen described her as “punky.”

But those symptoms appear to have been signs of adjusting to the sirolimus, and have largely passed. Riley’s longtime physical therapist, Karen Bensley, said recently that she thought Riley’s back had gotten a bit better, straighter and more flexible, since the trial began, and “it’s not just physical therapy, it’s a bigger picture than that.”

Is the sirolimus indeed having an effect? Please stay tuned. One big cheerleader for the trial, by his own description, is Dr. Steven Fishman, the Children's surgeon who operated repeatedly to remove Riley’s earliest growths. Another, he said, is Dr. Ahmad Alomari, the radiologist who first identified CLOVES.

“Those of us like myself, who cut things off,” Dr. Fishman said, “ or like Dr. Alomari, who inject boiling oil, we’re hoping for more modern things than these crude things that we surgeons and interventionists do.”

This program aired on April 27, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.