Advertisement

When A Burst Appendix Doesn't Kill You

First, the warning label for this story: A perforated appendix can kill you. If you experience symptoms of appendicitis, particularly sharp pain in the lower right area of your abdomen, get prompt medical care.

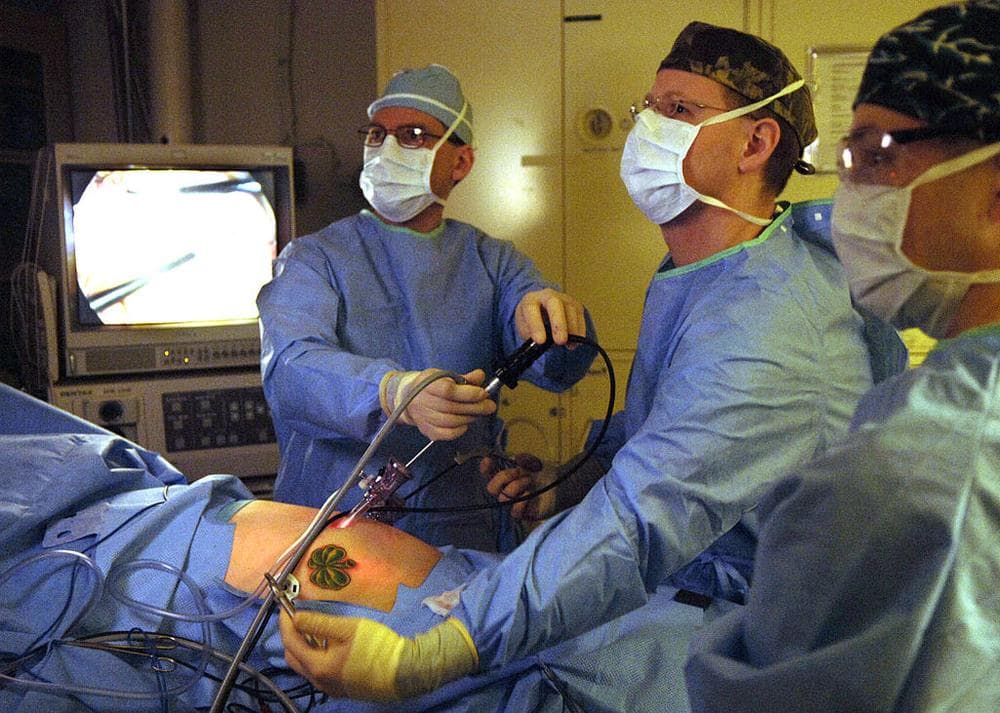

End of warning. Now for the surprising counter-example. You've seen acute appendicitis on hospital shows: The patient hunched over in unbearable stomach pain, rushed to the operating room for life-saving surgery to remove the organ gone awry. That's the popular image of appendicitis, and it does reflect reality. Appendectomies are the most common emergency operation that general surgeons perform — at a rate of more than a quarter of a million a year.

But medicine is ever-evolving, and the thinking on appendectomies has been changing in recent years. Where once acute appendicitis meant an instant trip to the operating room, that call is now becoming somewhat more nuanced, and is likely to become still more refined in coming years.

Our case in point: WBUR's news director, Martha Little. Her appendix has burst. And she's been working in the newsroom this week as usual, burst appendix and all. No, this is not the ultimate workaholism. She explains:

A couple of weeks ago, I thought I had food poisoning. I came in to work late that Monday, but worked long days all the rest of that week with mild shooting pains across my upper intestines. I thought I had contracted some weird virus.

Then came the weekend. My kids, my husband and I went to Fairfield, Connecticut for a family reunion. After two days of whiffle ball and frolicking in the ocean I popped open a Phil’s Blackberry Cider, ate a brownie (I know, I eat like a kid) and got in to the lukewarm hot tub. About a half an hour later, I felt myself crumpling onto the front lawn with intense abdominal pain.

I thought it was gas. My brother-in-law Remi, who just happens to be a general practitioner, was packing up his family to go home. "Remi," I said, “I’m actually in a lot of pain.” He palpated my abdomen and thought it might not be appendicitis because the pain was all over my lower abdomen, not just on the right side, and I had no fever, no vomiting.

I hauled myself into the house and lay on the couch in agony. Remi said that if it didn’t get better in a half hour, I should go to the emergency room. But with some Advil, it did get better. And after a hot bath, I felt really better, so we drove the two and a half hours back to Boston.

On Tuesday — because the doctor had no time on Monday — I got a CAT scan, blood tests and an X-ray. The CAT scan showed that there was, as the doctor put it, “something cooking” around my appendix and I should “get myself to the emergency room as soon as possible.” I didn’t panic. But I did wonder if I had only minutes to live.

After going to the wrong hospital, I finally made it to the Brigham & Women’s emergency room, where I was told I would likely have the appendix taken out that night. But upon further examination, the surgeon and his resident told me that I could wait eight weeks for surgery, and meanwhile they would treat the infection with serious antibiotics.

Eight weeks!? “What,” I said, "would happen if the appendix burst?”

“It has already burst,” they said.

What? I thought people died when their appendix burst.

No, I was told. Not always.

The body, they explained, has a way of “walling off” the perforated appendix so that the infection doesn’t spread. I asked another of the four surgeons who visited me in the acute care ward: How much time does one normally have? That is, until one dies from a peritoneal infection?

After our conversation, I realized he had never answered that question. He said: You would have known it was serious when your stomach muscles contracted so much it looked like a washboard. I wisecracked, “How could I distinguish that from my normal state?” He forced a laugh.

I am now on massive doses of the antibiotics Cipro and Flagyl, and staying away from alcohol. I have also read that heating pads and hot baths are not necessarily good for you when you have appendicitis. But I wonder if the water of the bath I took helped take the pressure off and slowed the infection. Who knows? All I know is that these days, if the burst appendix doesn’t kill you, they wait until the infection goes away and then take the thing out laparoscopically, in a same-day turnaround operation.

Wow, I said to Martha. Some people get "walking pneumonia." You have "walking appendicitis."

But I was gently corrected by Dr. Douglas S. Smink, program director of the general surgery residency program at Brigham & Women's Hospital. While "walking pneumonia," which is not a medical term, tends to be a milder form of the illness, there's nothing mild about appendicitis that has already reached the point that it has perforated the appendix. In fact, he said, it's more severe. In the United States, perhaps 80 percent of appendicitis cases get to surgery before the organ ruptures.

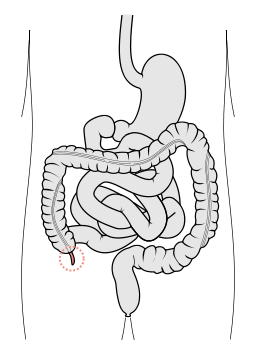

(A brief tangent: I suddenly realized that I could not picture a "perforated appendix." Was it like a water balloon exploding? A cardboard box torn along its perforations? Dr. Smink explained: The appendix, which is about the size and shape of a pinky finger, gets very inflamed until, in one area, its muscular wall gets so thin that it breaks open, releasing the bacteria-laden fluid inside. But the fluid doesn't explode out like a splatting water balloon; it seeps and oozes out as if the balloon had sprung a leak.)

Here's the good news for patients like Martha: The appendix is surrounded by other structures, mostly the intestine, and so, as she was told, the seepage can get "walled off." One theory, Dr. Smink said, is that a somewhat mobile layer of visceral fat called the omentum — nicknamed "the policeman of the abdomen" — could be drawn toward areas of inflammation to contain infection. So a patient can end up with a pus-filled abscess outside the appendix, covered partially by the omentum.

Still, why not just operate and get rid of the problem? It's not so simple. An area rife with inflammation is hard for surgeons to work with, Dr. Smink said, and an appendectomy could end up turning into removal of part of the intestine and colon as well.

So the idea is to give the patient antibiotics to fight the infection, wait as the inflammation subsides and then do an "interval appendectomy," after the waiting interval. (And by the way, even emergency appendectomies are done promptly but not with quite the urgency of old; waiting several hours appears to do no harm.)

Twenty years ago, Dr. Smink said, surgeons would go in and operate on virtually all cases of appendicitis, whatever the level of inflammation. But research found that for a certain group of patients, it was better to wait. Now, even the "interval appendectomy" is becoming controversial; a newer school of thought holds that some patients may do best with antibiotics alone, no operation at all.

The problem right now, he said, is that there's some data on the antibiotics-only strategy, but not enough to make clear which patients really need an appendectomy and which can get along without one. Patients who have a stone in the appendix, called an appendicolith, definitely need the organ removed, for example, but many other cases are not so clear cut. More research is needed, he said, to explore the effects of age, severity of illness and other factors on whether antibiotics-only treatment will work for a given patient.

Meanwhile, some studies also suggest that for many patients with uncomplicated appendicitis — the appendix still intact — antibiotic treatment alone may be enough as well. (I'm imagining myself as a patient with high-deductible insurance. That might pose quite a dilemma: Try just antibiotics, or take the safe but expensive route straight to the OR?)

Why are treatments for appendicitis evolving so notably away from the operating room? The general trend in surgery is that the less invasive, the better, Dr. Smink said. That's also why more than half of appendectomies are done laparoscopically — through a tiny incision — these days. And better research leads to a better understanding of the outcomes of treatments.

Bottom line: If Martha's appendix had blown 20 years ago, it would have long since been removed, possibly along with other parts of her. If it blew twenty years in the future, she might not end up having any appendectomy at all. You're part of medical history, I told her.

She didn't look very excited.