Advertisement

The Long, Bumpy Path Toward Effective Cystic Fibrosis Treatment

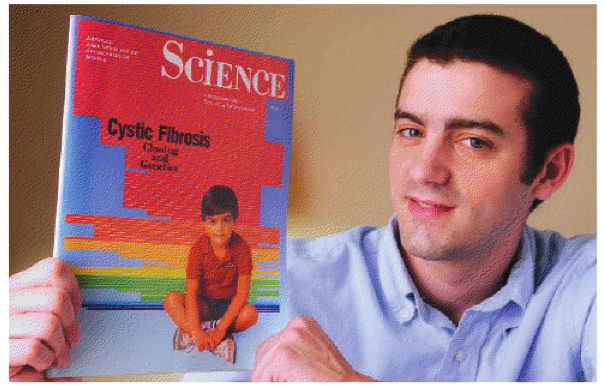

When he was 4, Danny Bessette was featured on the cover of Science Magazine. His was the new face of cystic fibrosis. A disease, recently lethal to children his age was now on the verge of being beaten, the coverage suggested. After all, the gene had just been discovered.

Twenty years later, he was featured in Science again, symbolizing the painful scientific realization that discovering a gene is still a long way from developing a cure.

Danny Bessette is 27 now, and if he still represents something larger than himself it’s the patience and fortitude that he and others touched by disease have had to exhibit during the ups and downs of scientific discovery.

And yet levels of optimism today are probably as high as they’ve been since 1989. Drugs developed out of the understanding of how the gene works are just now reaching patients. They have brought dramatic improvements to some. It’s not yet clear whether they’ll be able to help Bessette.

Cystic fibrosis, as scientists discovered in 1989, is a defect in a gene called CFTR. That gene produces a protein of the same name, which acts like a gate allowing salt and fluids to enter and exit a cell. If the salt and fluids get trapped inside the cell, the outside of the cell dries up and the mucus that lines it isn’t diluted enough. This thick mucus traps bacteria and causes infections, scarring and weakening the lungs over time.

“Think about it like spaghetti,” suggests Dr. Bonnie Ramsey, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine, and cystic fibrosis expert. “If you have spaghetti in a vat, you can stir it easily with free-floating water.” If you pour out the water, “you get a glob” of sticky pasta.

Most people with cystic fibrosis, which affects about 30,000 Americans, die from lung infections caused by this thick mucus. They used to die in childhood, often at the age Bessette was when he first appeared in Science.

Aggressive lung therapy to bring up the mucus, medications to thin it, and improved delivery methods for antibiotics have all been extremely effective. The average lifespan of someone with cystic fibrosis is now nearing 40. (Atul Gawande wrote about CF treatment and why the lifespan of patients varies so much from center to center in The New Yorker in 2004.)

It isn’t easy, though. Bessette takes 40-50 pills a day, many to help with digestion – which is also effected by the mucus – and spends 2-3 hours a day forcing himself to cough gunk out of his lungs, a process he describes as “time consuming and energy consuming.” Though he was strong enough to play hockey in college, he says he doesn’t have as much strength anymore. He recently had to cut his hours at a real estate management office from part-time to “just working here and there,” he says.

What Bessette needs, like everyone else with cystic fibrosis, is a way to treat the underlying disease, not just the symptoms – a way to fix the genetic glitch that causes his problems.

The first big success to come out of the growing understanding of this genetic glitch was approved by the FDA in January. The drug, known as Kalydeco, has been shown effective in about 4 percent of people with cystic fibrosis – those whose CFTR salt gate is stuck shut. Kalydeco, made by Vertex Pharmaceuticals of Cambridge, pries opens the gate.

It’s still unclear how effective the drug will be in the long term and whether it will extend the lives of people with this so-called G551D mutation, but so far, the drug has been described as miraculous. CommonHealth interviewed a 41-year-old last year who said her winter on the drug was her first ever without a devastating illness, and that she could now, for the first time, imagine growing old. Virtually everyone in the United States with this mutation is now taking Kalydeco.

“The improvement that we’re seeing with Kalydeco is so much more than we see with any other intervention we’ve ever had,” says Robert J. Beall, president and CEO of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, which helped fund Kalydeco and other drug research.

Most of those with cystic fibrosis, including Bessette, have a more complicated genetic problem than that group. Their CFTR gate doesn’t work properly because the pieces needed to make it are deep inside the cell, instead of near the surface. For them, Vertex has developed a second drug, VX-809, designed to get the gate pieces set up in the right place, so Kalydeco can get them working properly.

There was some controversy over this combination therapy back in May, when the company released interim data that was extremely optimistic – and unfortunately, wrong. The morning it corrected the data, Vertex’ stock plummeted 18 percent. The researcher who led this leg of the study, Dr. Michael Boyle, says the error was a mathematical one by a company hired to run the numbers. He says he was leery of releasing interim results to the public, but felt compelled to because the company was planning for the next phase of research, and the federal government requires full disclosure of open trials before allowing for new ones.

The trial aimed to determine the safest, effective dose of VX809. Three groups of about 20 participants each – a low-, medium- and high-dose group – received VX809 for 28 days (the fourth group was given placebos), before being given Kalydeco for an additional 28 days.

Once corrected, the trial results were still good enough for the company to continue studying the drug – which is what matters for patients like Bessette.

“There’s an absolute commitment to phase III,” said Boyle, who directs the Johns Hopkins Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program.

The next round of trials, which will include hundreds if not thousands of patients on a high dose, will be crucial to the drug’s future, and possibly Bessette’s. He has the mutation that the double-drug regimen is intended to fix.

“You’re always a little cautious on your optimism,” he said a few days ago, as he drove from North Carolina to his home in Vienna, Virginia. But “it’s definitely a glimmer of hope.”

Karen Weintraub, a Cambridge-based health and science writer, is a frequent contributor to CommonHealth.

This program aired on July 17, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.