Advertisement

A New Device For A Chronic Bladder Problem

The pain of interstitial cystitis can be as unrelenting as the urge to urinate. Some women go 50-60 times a day – and night. They often feel isolated by their symptoms, and misunderstood by their doctors.

The chronic bladder problem, affecting about 300,000 Americans, is known to be tough to treat. It’s unclear what causes flare-ups, with different triggers in different women. (Men can get interstitial cystitis, too, as can children, but it’s much rarer.) It may take years for a woman to get a diagnosis – for a doctor to believe that it’s not just “all in her head” – and years more to find a treatment that works at least some of the time.

“It is a very complicated disease and these patients are in very tough shape,” said Michael Cima, the David H. Koch professor of engineering at MIT. “There’s a real medical need.”

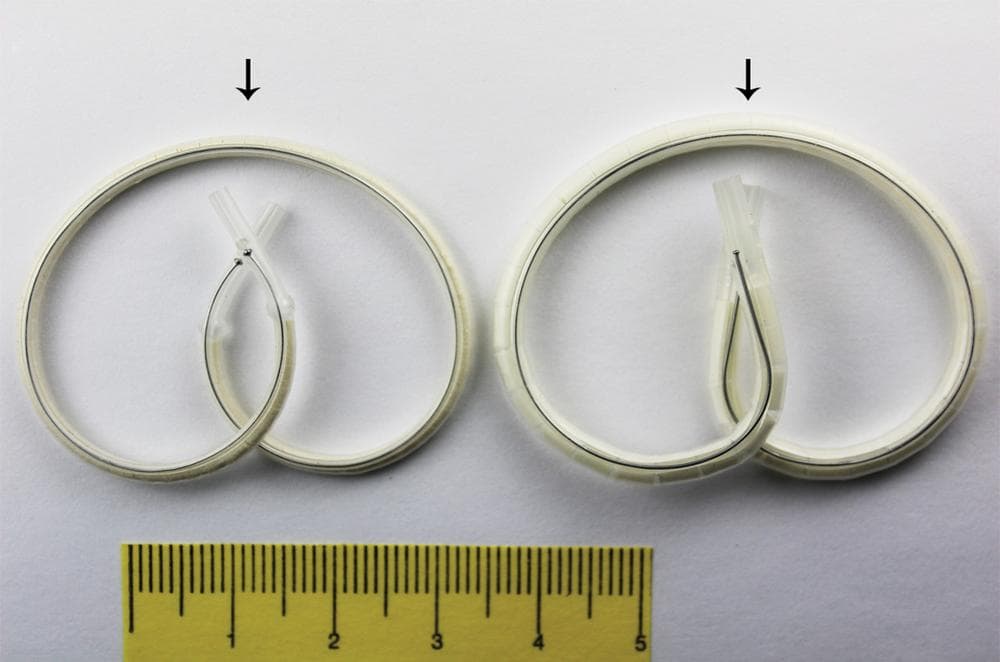

That’s why Cima, along with a company he cofounded, has developed a device to deliver the painkiller lidocaine inside the bladder, for as long as two weeks. Other similar devices are either so large that they cause pain, he says, or so small that they slip out of the bladder when the person goes to the bathroom.

Cima’s device, published in the current issue of Science Translational Medicine, unfurls once placed inside the bladder into a pretzel shape, so it stays put until removed by a doctor.

“This is the first time anybody’s developed a continuous release of anything in the bladder,” he says. “While other people have tried to do this, they weren’t tolerated and ours was.”

So far, the device, called LiRIS, for lidocaine-releasing intravesical system, has been tested in just 28 patients, 10 of whom had no bladder problems. The first round of testing was to establish the safety of the device – which it did, Cima says – and the dose of lidocaine required to help patients. Two different doses were tested, 200 mg and 650 mg a day. The lower dose seemed to be just as effective as the higher one.

The scientists were surprised to discover that the device had a long-term benefit for many of the patients. Instead of just helping for the two weeks it was in their bladder, patients reported reduced symptoms for two and a half months after it was removed.

The device now needs to be tested in many more people to see if it will have a similar benefit and safety profile.

It’s not a new idea to deliver painkiller directly into the bladder to treat pain, says Dr. Jay Joshi, CEO and medical director of National Pain Centers, clinics outside of Chicago. But “any option that allows patients to get a substantial amount of long-term relief with a short-term treatment is obviously very welcome.”

Joshi says he’s not surprised that the device also helped long-term. Pain is like a pathway, he says. Once the pathway has been created, the pain can continue even when the initial cause of pain has ended; once the pathway is blocked, in this case by the lidocaine, it makes sense for the pain to go away, at least for a while.

Lidocaine is generally a safe medication, Joshi says, though he’s concerned about installing a device that has multiple doses of the drug. “If this thing ruptures, there’s an extremely high chance of bad things happening very quickly. That is a major concern,” he says.

Purnanand Sarma, president and CEO of TARIS Biomedical Inc., of Lexington, which is commercializing the LiRIS device, disagreed. He wrote in an e-mail that the 14-day dose is typically the same delivered at once to many of these patients. And because the bladder empties every 2-3 hours, Sarma said, “the potential absorption window, should the device be damaged and release a substantial amount, is relatively short.”

Cima says treating bladder pain is a starting point. What he’d really like to do with LiRIS, he says, is help bladder cancer patients, many of whom have to have their lesions removed multiple times because of recurrence. Treating cancer is even more complicated than treating bladder pain, he says – which is the problem he really set out to solve when he designed he LiRIS.

“Could we do a better job of keeping the chemotherapy in [the bladder] long enough to kill all the cancer? That was the genesis of this idea,” Cima says.

Karen Weintraub, a Cambridge-based health and science writer, is a frequent contributor to CommonHealth

This program aired on July 19, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.