Advertisement

A Biological Basis For Jewishness

By Karen Weintraub

Guest contributor

One of the benefits of genetics is its ability to tell us about our collective past. Genetic research has revealed, for instance, that people of European – but not African – descent, carry some Neanderthal genes.

Genetics also has the power to test our oral history, the traditions that a particular group has been passed down from one century to another through word of mouth. A new study from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University shows that the oral tradition of Judaism is largely accurate.

Jewish tradition holds that the Israelites were dispersed beginning with the destruction of the first Temple in 586 BC, and accelerating in the first century AD with Roman Empire’s destruction of the second Temple.

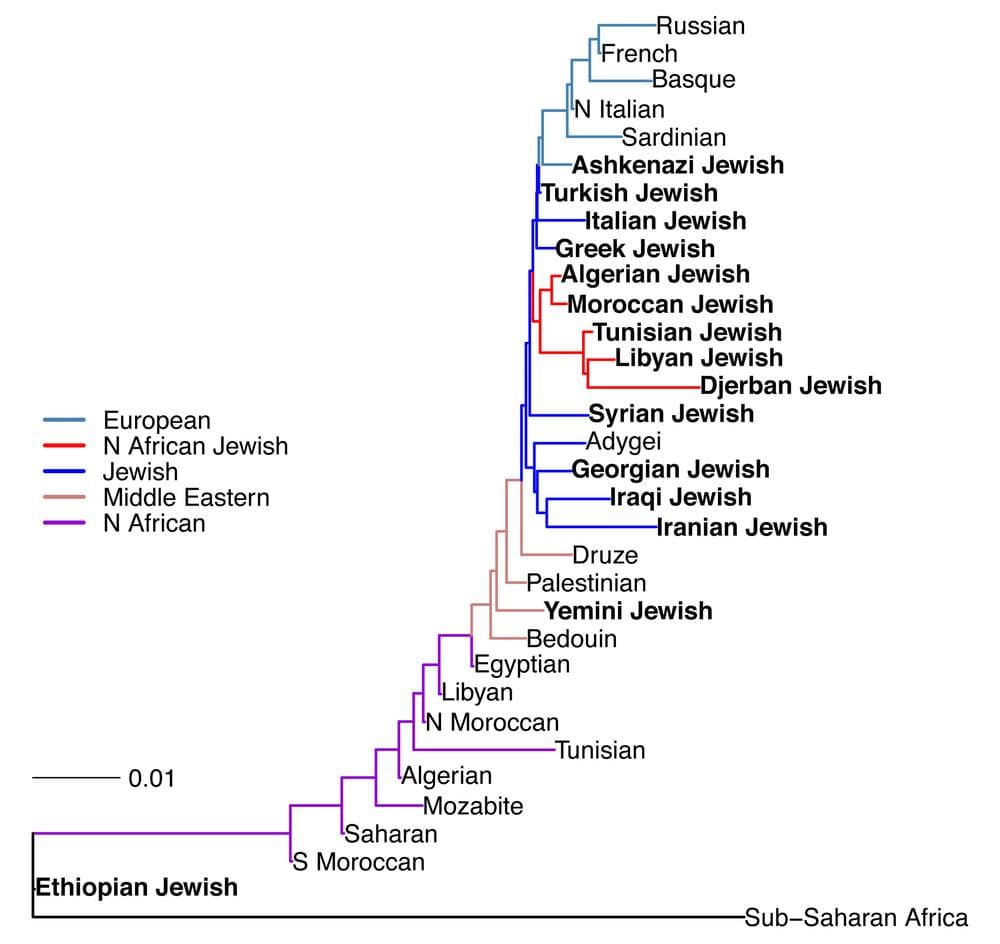

Albert Einstein researchers had previously shown that Jews who come from Eastern Europe – known as the Ashkenazi – and those from Spain, Greece and Turkey had common genetic roots, along with Jews from Iran, Iraq and Syria. The new study brings North African Jews into the family tree, and supports “the case for a biological basis for Jewishness," according to study leader Harry Ostrer, a professor of pathology, genetics and pediatrics at Einstein and director of genetic testing at Montefiore Medical Center.

Jews from each of these geographic areas resemble each other more than their non-Jewish neighbors, the study found. The Middle Eastern and European Jews genetically diverged about 2,500 years ago, roughly coinciding with the destruction of the first Temple.

“It’s been useful for putting non-Ashkenazi Jews on the map,” Ostrer said.

Tracing these genetic roots is more than just curious history. The goal of looking at distinct populations is to better understand genetic links to diseases such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease, as well as genetic disorders such as the fatal nervous system disorder Tay-Sachs and breast cancer gene mutations that are known to be linked to Jewish ancestry, Ostrer said.

Some DNA segments distinct to Jewish populations carry disease risk, while others offer protective genes. By analyzing these genetic differences and the functions of these genes, researchers will gain insight into diseases that affect much larger swaths of people, said Ostrer, who has also conducted research on other genetically distinct groups of New Yorkers. “I really see this as the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

Not all health risks are purely genetic, of course. Ostrer thinks that culture may explain the frequency of obesity-related diabetes noticed in American Jewish adults at the turn of the last century. Jewish people were bred in conditions of scarcity because of anti-Semitism overseas. “When they came to the US, they were nutritionally challenged in the same way other immigrant groups are now,” Ostrer said.

The study also revealed that the African Jews formed two genetically distinct groups: one included Moroccan and Algerian Jews, related to the Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492, and the other, Tunisian and Libyan Jews.

Although Jews and Palestinians are closely related, they are genetically distinct populations, Ostrer said. “We were able to define the boundaries of each of these populations and the extent to which they overlap.”

Smaller Jewish populations, like those from Ethiopia, India and China, were probably the products of conversion, rather than descendants of early Israelites, Ostrer said, adding that he has not yet studied those groups in sufficient detail.

Jewish populations were isolated by their beliefs, practices and language, though they did intermarry some with surrounding populations. Today, American Jews commonly intermarry, diluting disease genes.

Before that genetic distinctiveness is gone entirely, Ostrer said, Jews should volunteer to get their genes scanned for research.

“Most of us are part of a family,” he said.

Karen Weintraub, a Cambridge-based Health and Science journalist, is a frequent contributor to CommonHealth.

This program aired on August 7, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.